Originally published October 2022.

A comparison of today’s inflation context vs that of 1970s.

Most economists work for financial firms and their interests are served if markets expect low interest rates. Perhaps for this reason, these folk have tended to opine (incorrectly) that inflation would not become an issue. I have the opposite conflict. Since farmland is likely to significantly out-perform in times of inflation (see https://www.craigmore.com/commentaries/the-return-of-the-land/) I have an incentive to predict inflation, since this may prompt investors to allocate to Craigmore’s farming and forestry partnerships. My readers will need to judge whether my inflation forecasts of 2020 (https://www.craigmore.com/commentaries/exploring-inflation-risks/) and hereunder turn out to be as inaccurate as those of mainstream economists.

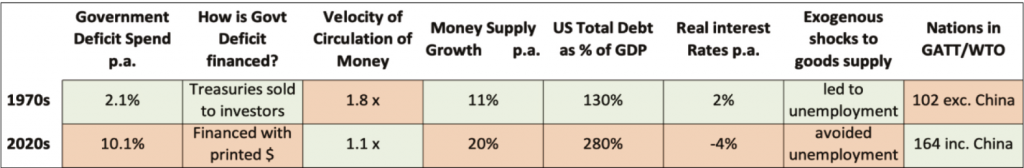

Inflation factors in the 1970s vs todays

When researching this piece, I was shocked to discover how comparatively poor current US policy settings are relative to the 70s.

The table below shows that six key inflation factors are now worse (red) and only two factors (green) are better than they were in the 70s.

Those factors ranking more poorly now than in the 70s are:

Average US government deficit: in the three years to 2022, there will be average US government deficits of over 10% of GDP compared to an average of 2.1% in the 70s. The CBO estimates 5% deficits for the remainder of the decade, still twice the level of the 1970s.

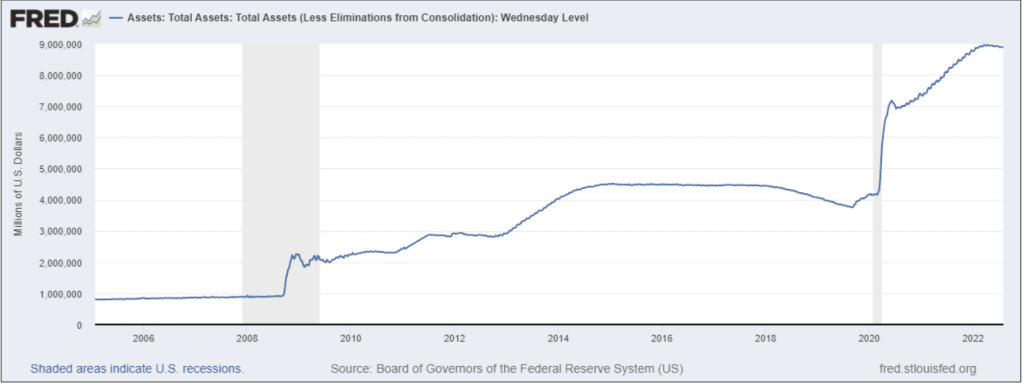

How are government deficits financed? In 2020-2021, the US financed its government deficits by central bank money printing. In the 1970s, the US government financed its deficits the old-fashioned way – by issuing bonds to investors. While the quantitative tightening that began this year is in fact ‘un-printing’ some of the Fed’s balance sheet, a large genie still needs to be put back in the bottle (see FRED graph below).

Money supply: by December 2022, the US money supply will have grown by 20% per annum over three years, compared with 11% pa in the 70s.

Leverage: in the 70s, US non-financial debt was stable at 130% of GDP, within this federal debt was 30% of GDP. US debt to GDP more than doubled to 280% by the end of 2021, of which Federal debt is almost half at 130%. Does this leverage create an inflationary ‘policy bias’? Might the Fed keep interest rates lower than it should, in order to avoid business failures and high US debt service costs?

Real interest rates: although US inflation in the year to June 2022 was 9.1%, interest rates are still below 5%, so that real interest rates are negative by -4%. Interest rates were on average 2% above the rate of US inflation in the 70s.

Exogenous shocks: although both decades faced supply shocks, government and monetary support during 2020 to 2022 prevented business failures and unemployment. As a result, there is no slack in the major economies. The energy shocks of the 70s and a series of recessions led to corporate failures and unemployment (which averaged 8% during 1974-79). The absence of corporate failures in the 2020s contributes to a zombification of supply, reducing its ability to catch up with demand (‘The rise of zombie firms: causes and consequences’, BIS Quarterly Review, Sept 2018).

Two factors are less inflationary than the 1970s:

Velocity of money: in the 70s, velocity of money averaged 1.8. Markets recycled each dollar of money supply into one dollar and 80 cents of GDP. Velocity has now fallen to 1.1.

Globalisation: the US and other economies are more ‘open’ now than they were in the 70s. Inflationary policies at home can be exported to other countries (hence wage growth in China has averaged 11% from 2010 to 2022).

How hard will it be to control inflation?

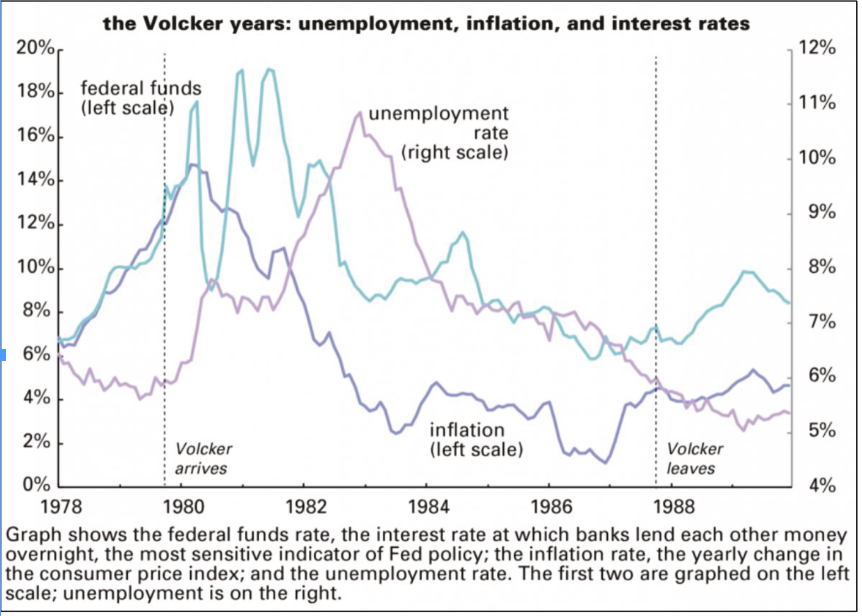

Paul Volker, when chair of the US Federal Reserve, proved in the four years from 1979 to 1983 that tough monetary control can reduce inflation, but he had to raise interest rates to 18%, shortly after which inflation peaked at 14.5%.

Unemployment then began a three-year rise, from 6% in 1980 to 11% in 1983, during which period he kept interest rates 4% above the rate of inflation, ie, about 8% higher than our present policy settings.

Once inflation is reverberating around an economy, it can take a lot to quell it. Input and labour costs put pressure on corporate margins, corporates respond by raising prices. The resulting inflation is then a merry-go-round. This is especially true if, as at present, employment markets are tight, markets for goods and service are under-supplied, corporate power has become concentrated and monetary conditions are lax.

Larry Summers was quoted in the FT on 4 August explaining that we’d need a reasonably deep recession to quell inflation now (US unemployment is currently 3.5%):

“We need five years of unemployment above 5% to contain inflation – in other words, we need two years of 7.5% unemployment or five years of 6% unemployment or one year of 10% unemployment… These are numbers that are remarkably discouraging.”

What is likely to happen next?

I remain unconvinced that central banks are ready to take the tough decisions Larry Summers talks about (https://www.craigmore.com/commentaries/no-constituency-for-sound-money/).

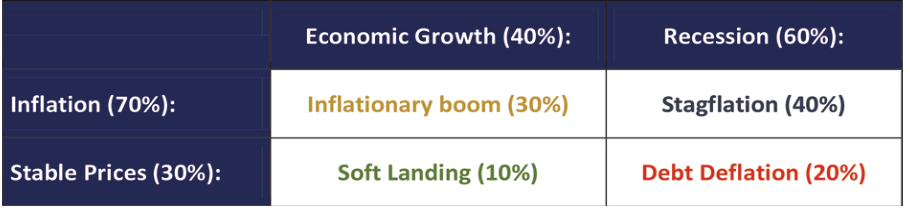

Just like in the 70s, inflation will stop and start this decade, but on average I forecast a 70% probability of on-going elevated inflation (over 4% pa). This will express itself as an inflationary boom if we don’t fall into recession or into a period of stagflation.

I think stagflation, at 40%, the more frequent outcome in the decade. A scenario which characterised a number of the stop-start fluctuations of the 1970s.

The scariest scenario is a debt deflation (20%). This would see widespread debt defaults and consequent fall in prices of assets. That this is so unattractive it may lead to an inflationary bias in economic policies is the key point of this Craigmore Commentary.