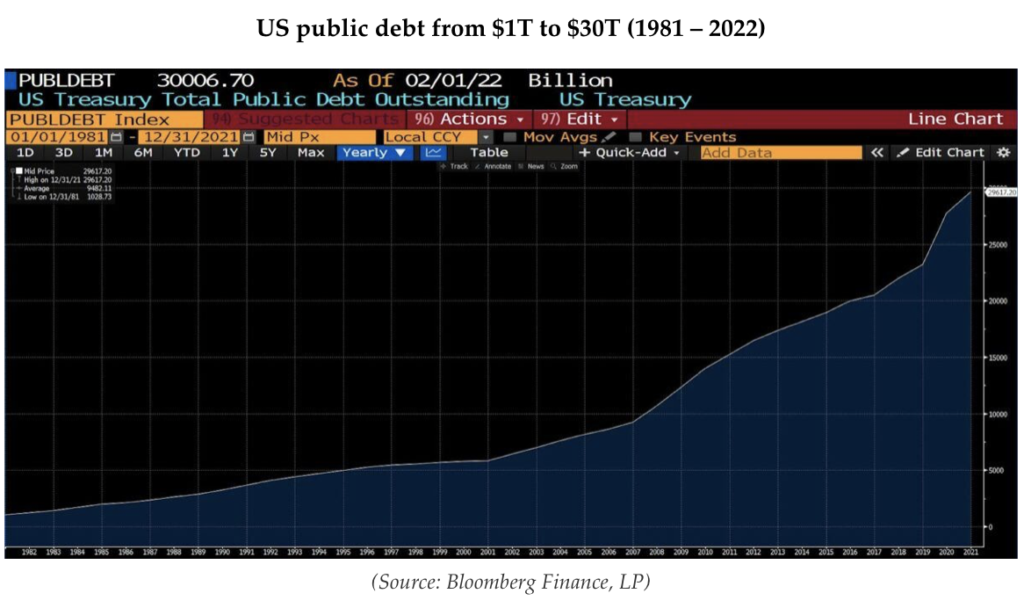

On Tuesday, February 1, 2022, the United States national debt surpassed $30tr for the first time.

It’s the latest in a series of recent fiscal and monetary benchmarks received with increasing blitheness. I counted only a handful of headlines reporting on it. Two of which, interestingly, were The New York Times and Xinhua, the official press organ of the People’s Republic of China.

In 1789, the youthful US government assumed responsibility for $75m (approximately $1.6bn in 2022) in debt incurred to fight the War of Independence. In less than 50 years, and amid fluctuations, that number had been paid down to less than $40,000 (roughly $1.25m in 2022). While the Civil War was still being fought, the national debt surpassed $1bn (about $22bn in 2022) for the first time.

By the mid-1970s, following the Progressive Era, World Wars I and II, the Great Depression and New Deal, the Cold War, Korean War, Vietnam War and the Great Society, the debt hit $500bn ($2.5tn in 2022). In 1981, the $1tn barrier was crossed. The $10tn mark came and went in 2008, $20tn in 2017, $25tn in 2020 and here we are.

There are two particularly noteworthy things about this particular debt level being hit at this moment. First, the Federal Reserve is in all likelihood within 60 days or less from beginning its first rate hike campaign – one targeting not a return to normalcy, but rising price levels – in decades. And this one is being undertaken with a sense of urgency. That matters, because rising rates will increase the debt service (interest payments the US government must pay on the outstanding Treasury securities). The second is that the Congressional Budget Office projected two years ago that the $30tn debt number wouldn’t be hit until 2025. And the US gross national debt exceeded the size of the US economy (GDP) in 2021, nearly a decade faster than expected.

And unless I am mistaken, credit rating agencies issued nary a peep when the $30tn milestone was hit.

And so it goes. Traditionally, a crescendo of warnings waft up at these moments, only to dissipate within a few days. Predictions of impending fiscal catastrophe are as schematic as breathless warnings of impending hyperinflation (“Right around the corner!”) any time the Fed engages in expansionary policy measures. In both cases, rather than raising awareness, they are increasingly received as empty, Cassandric screeds: episodically less heard and even then summarily brushed off.

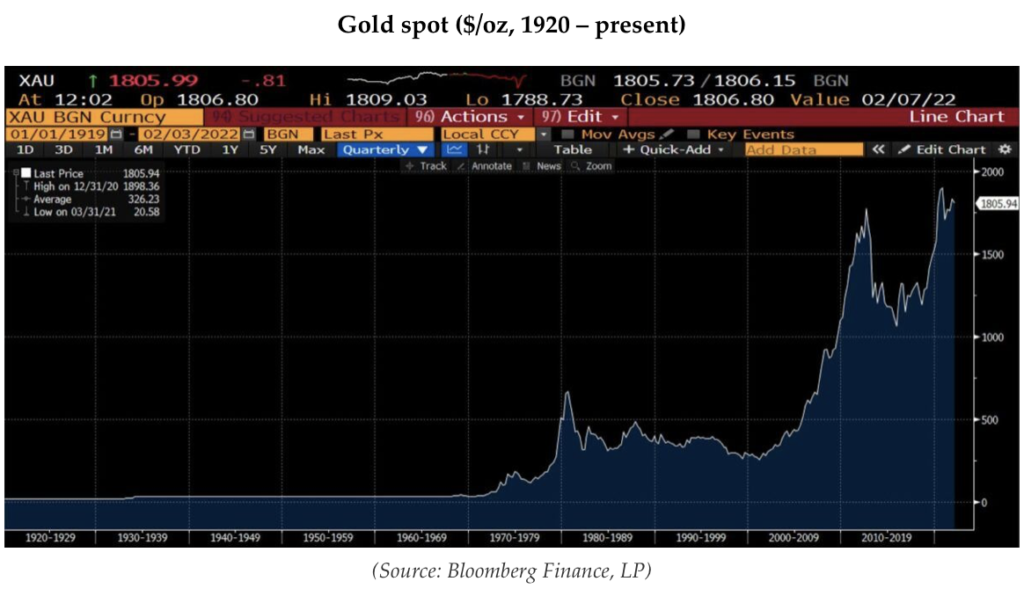

Instead of engaging in unsubstantiated forecasting or policy attitudinising, a more productive and considered approach would focus on social science, historical precedent and moral principle. It is precisely because we do not and cannot know where and when national debt levels are ‘too’ high, or what will happen to global interest rates as the slug of US debt lumbers higher, or what the next congressional spending whim will embrace, that we should look to the very public record of disastrous fiscal (and monetary) extravagance. We know that rising indebtedness brings colossal opportunity costs, which in turn affect every American citizen and our national security. And clearly, in a world of unlimited desires amid scarce resources, political decisions to trade the future for the present tempts further, possibly more withering assaults upon the already decremented soundness of the US dollar to meet rising obligations.

Not knowing precisely when or what the exact circumstances will be that bring decades of short-sighted monetary and fiscal policy to a head need not, and should not, prevent individuals from taking the necessary steps to safeguard the fruits of their labours.

Originally published by The American Institute for Economic Research and reprinted here with permission.