He may be one of only a handful of senior-ranking Ministers in Downing Street to have avoided catching Covid-19 but the pandemic has left the Chancellor of the Exchequer with a fiscal headache.

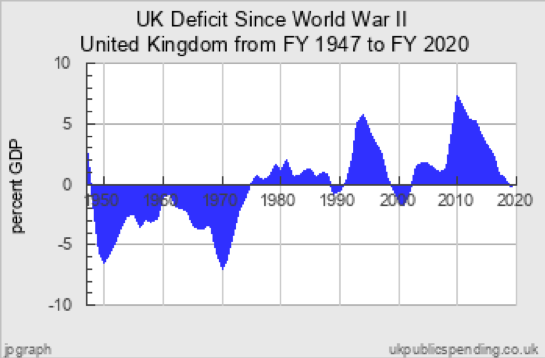

The last time the UK debt was bigger than the output of the economy itself was in the second world war. It took the iron determination of Sir Stafford Cripps to impose genuine austerity on the country after the war, and to produce annual surpluses to pay down the debt that had been incurred. The scale on the chart opposite is not big enough to accommodate this year’s deficit at £300 billion – somewhere around 20 per cent of GDP.

A Government can normally only run a deficit if the markets are willing to lend to it, but for this crisis the Bank of England has taken powers to finance the deficit through monetary financing – printing money for the Government instead. The Bank is already significantly expanding the money supply by purchasing bonds in the secondary market (the QE programme) and it will have to keep half an eye on the consequences of these operations for sterling and for inflation.

With the monetary accelerator pressed firmly to the floor – and after a massive Covid-19-related fiscal expansion – confidence in Mr Sunak’s running of the British economy will soon depend on his finding the public spending brake pedal. He will be announcing the results of his fundamental spending review this Autumn, setting out expenditure totals for each government department for the following three years. Then a Budget is due to take place in November, when he will be looking for new sources of revenue too.

When no-one is making much money and you need people to carry on spending, it makes little sense to hike income tax or national insurance. Keeping people spending also helps to maintain income for the Government from VAT and other duties. Corporation tax, on the other hand, is an easy target for a Chancellor looking for a tax grab. The Conservative Party justified cancelling its planned corporation tax cuts during the election campaign last November by saying that it would spend the savings on the NHS instead. Mr Sunak may now feel he can go further and demand corporate Britain pays a penny or two more in corporation tax to cover increases in NHS expenditure.

Circumstances have forced Mr Sunak to become a radical Chancellor, and some fear that his review of capital gains tax will see punitive taxes imposed on wealth creators. He may scrap entrepreneur’s relief, but the £12,300 allowance is probably safe, as is CGT relief on the sale of a main home. However, the main rates of CGT could rise (from 18/28 per cent) back up to the level of an individual’s marginal income tax rate (20/40/45 per cent).

More worrying would be the introduction of a capital value tax, which has been mooted by the Treasury in its fundamental review of business rates. Business rates have many faults, not least the level of the multiplier (which at around 50 per cent of rental value massively disadvantages bricks and mortar retail as against online retail). Replacing a tax on occupants with a tax on landlords is likely to deter property companies from investing in office, retail and hospitality spaces. If the Chancellor wants shabby, decaying high streets across the country, a capital value tax is surely the way to go.

That leaves the other great unreformed property tax, council tax. There has not been council tax revaluation since it was introduced in 1991 as a replacement for the poll tax by Michaels Heseltine and Portillo. There is a good reason for that: a comprehensive council tax revaluation would create as many losers as an examination board with an algorithm in a year of pandemic. But the Chancellor could announce a limited revaluation of Bands G and H properties (those valued at more than £160,000 in 1991), with a view to creating new bands at the top and bringing in significantly more revenue from those living in the most expensive properties.

There is growing speculation that a levy on personal wealth may be introduced. Like all windfall taxes, these are most effective when deployed using an element of surprise. Flagging up an intention to come after people’s wealth is a sure way to send money scurrying to safe havens overseas. Mr Sunak has shown that he is willing to take extraordinary measures in extraordinary circumstances, and he may feel that he can get away with a one-off tax raid on property or savings. The risks are that he sends all the wrong signals about post-Brexit Britain to the world, and all the wrong signals about the Conservative Party to an aspirational electorate. What would be the point of trying to make it in Britain if you thought that even a Conservative Chancellor might come after the wealth you had worked hard to create here?

Better that the Chancellor uses today’s