Central banks do not set interest rates.

To be specific, central banks in large western democracies with open capital markets and flexible exchange rates do not set interest rates, other than for overnight money. That’s right! If policymakers went on strike – as security workers at the Bank of England did recently – there would be no loss of coverage or continuity for interest rates. Banks would be free to raise or lower their own interest rates on a multitude of products – commercial and individual – and interest rate contracts would continue to be traded on exchanges and over-the-counter. Institutional and retail investors would buy and sell government and corporate bonds as they saw fit. Financial and non-financial corporations would still issue bonds based on prevailing market conditions. Life would carry on seamlessly.

Sidney Homer and Richard Sylla gave the game away in their History of Interest Rates, first published in 1962. They quote Mesopotamian interest rates on grain and silver from around 3000BC and trace the history of interest rates via Greece, Egypt and Rome to the Dark Ages, medieval times, and Renaissance to modern Europe and North America. There is no entry for central banks in the index of this 700-page tome.

What then, is the point of the regular monetary policy committee meetings held at the US Federal Reserve, European Central Bank and Bank of England, not to mention the international calendar of jamborees and junkets? The Bank of England is clearly thinking along similar lines, having reduced the frequency of MPC meetings from 12 to 8 per year. The primary purpose of these gatherings is to divert attention from the things that really matter, over which the central banks have little or no control. Central bankers are like Tommy Lee Jones, alias Agent K in the movie Men in Black, inviting the general public to look at the bright light that instantly erases their memory of things they weren’t meant to see or think.

In this media age, everything must be defined by time and space, so that it can be captured on video footage. Natural and man-made disasters are a real nuisance. News agencies much prefer that stories are scheduled so that they can be sure to be represented. If there wasn’t a press conference, it didn’t happen. The BBC has taken things to such an extreme that very often they are the news! This has the added attraction that they have the exclusive.

The financial news media lives with twin terrors: first, that something important happens and they haven’t noticed; second, far worse, is that nothing important is happening. Faced with hours and hours of programming to fill, a central bank policy meeting announcement is a godsend on a wet Thursday morning. Better still, a boondoggle like Davos, Aspen or Jackson Hole, which yields dozens of interviews with the rich and powerful. Incidentally, the Kansas Fed selected Jackson Hole in 1982 because of its trout fishing: Fed chairman Fed Volcker was a keen fly-fisherman.

The notion that market interest rates could jump 25 basis points in a day, or 100 basis points in a month without prior notice is anathema to this consensual way of thinking. Surely, a big move must have a big trigger? Actually, no. Big market moves happen when markets reach critical states: when seemingly trivial occurrences expose the invisible stress fractures within the sand pile.

Sometimes, the merest central bank actions trigger major market moves. Ben Bernanke’s glance towards the asset purchase exit on 22 May 2013 was sufficient to spark a 100-basis point rise in 10-year US Treasury bond yields by that year’s end. At other times, central banks have sought to send a strong signal to the money markets, to no avail. Central bankers’ new fondness for macro-prudential policy measures is lost on the financial markets. Yet, the biggest mistake is to suppose that market interest rates only respond to central bank triggers.

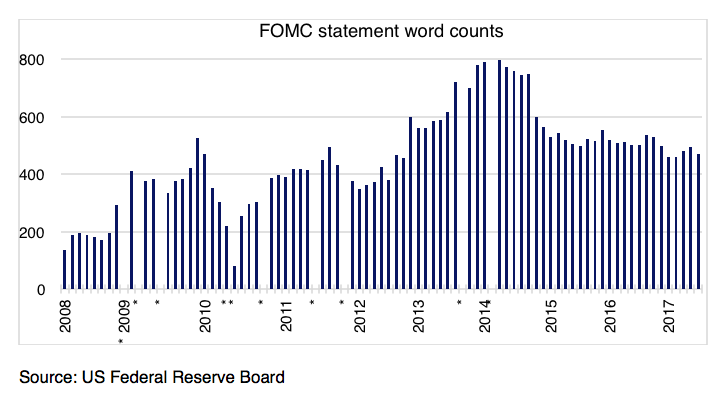

Policymakers are, of necessity, control freaks. Their problem is a massive loss of control of their domestic yield curves that has occurred stealthily over the past 25 years. Central banks have become overshadowed by other financial institutions in size, diversity, ingenuity and complexity. Silently, the central banks have exchanged control of interest rates for mere influence on interest rates. If they were in control, they could sit in their signal box playing bridge. Having only influence, they live in a state of nervous exhaustion, forever seeking new ways of steering interest rates in their desired direction. The increasing length of FOMC statements (in the chart) is an eloquent indication of this restless innovation.

Monetary policy in the US, Europe and the UK has mutated from a simple call on short-term interest rates to a multi-faceted strategy for collateralised liquidity injections, asset purchases, duration plays, currency swaps, term lending facilities and forward guidance. If central banks were still in control, they would be pulling levers in the signal box. Instead, they are running around like demented circus performers, making policy on the hoof.

If central banks appear to have tamed their respective yield curves, this has come at the price of heavy-handed one-sided interventions in the bond markets. The reversal of this extreme monetary accommodation carries abundant risks in terms of erratic and extreme market reactions. Their strengthened influence over the yield curve since 2015 comes at the expense of weakened influence in the future.

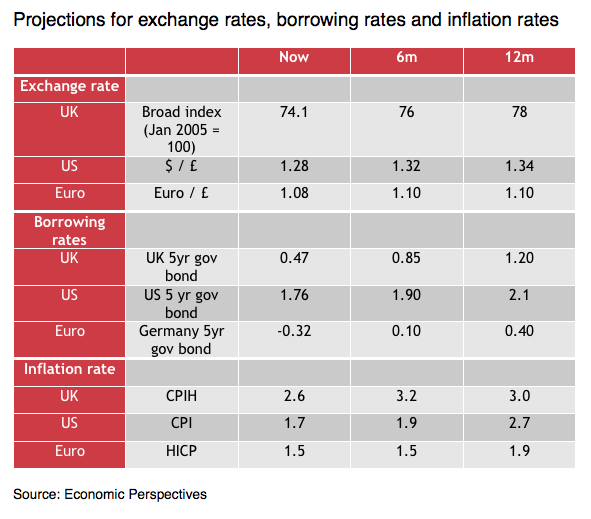

The message to real estate investors is “beware the unannounced interest rate increase.” The past reluctance of policymakers, especially in Europe, to withdraw stimulus is not a reliable guide. The brief but happy coincidence of rising global economic growth has presented the central banks with a rare window of opportunity to signal both higher rates and balance sheet restraint. Regardless of what is announced, there is the risk of a disorderly exit from fixed interest trades over the next 12 months. Financial markets will take their cues from inflation, fiscal policy and politics.

In future articles, I will explore some of the big issues that impinge upon the future course of price and wage inflation and interest rates. Many believe that interest rates will stay very low for a very long time because of the 3 Ds – debt, demographics and distributional inequalities in income. I will seek to counter this view using a wider lens of politics, economics and history to argue that policies are bending – and will bend – towards the accommodation of inflationary pressures and that investors will adjust their behaviour accordingly. Weakening economic growth and strengthening inflationary trends coincide from time to time, prompting a radical re-think of political and economic priorities.