How GameStop’s landlord was too slow off the mark with an opportunistic equity raise.

There are two main areas that cause confusion between participants in the public (listed) and private (unlisted) markets: the divergence of a share price away from the underlying asset value, and the difference in the fund raising mechanics and speed of execution of the two quadrants. For a new unlisted fund, it could take six months to two years to reach first close. Indeed it may be aborted as an idea after two or three years without raising the money. In the real estate equity market, particularly in the US but also in the UK, the time from first idea to the money sloshing around in the corporate bank account can be measured in days but more normally weeks. The corollary of this is, of course, that you have to be nimble in raising equity capital, otherwise there is a significant risk of being crowded out.

To remind ourselves: there are three types of equity fund raising: (i) opportunistic, (ii) to support an acquisition, (iii) to recapitalise. Leaving aside the obvious variable of pricing (discount to current price) and terms (new for old), in the first two cases the key determinants are market sentiment towards the sector and competing issues. In the third case, specific factors relating to the company, its strategy and, crucially, its shareholder base are the key. That is why three companies with exposure to a similar asset class had very different reactions to their recapitalisation proposals. Intu’s failed; Hammerson’s succeeded but on hugely dilutive terms and accompanied by disposals; Unibail Rodamco Westfield’s was rejected and replaced with a revised strategy of self-help via disposals.

There is, however, an even better example of crowding out, the specific equity market mechanics of what is known as a bear squeeze, and a share price diverging from underlying value and determining the corporate strategy. The REIT involved is a Santa Monica-based mall owner called Macerich.

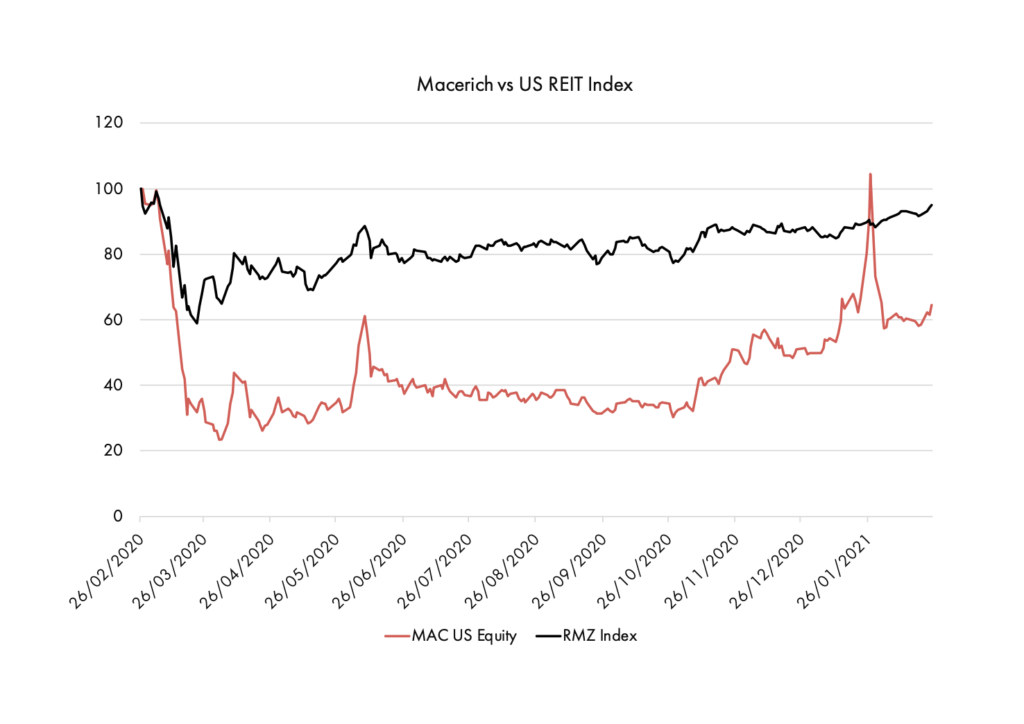

In common with other mall owners, the company had been facing significant headwinds. The impact of covid-19 exacerbated the well-known issues of growth in online shopping and oversupply of malls. In common with many retail REITs, a number of funds had built up short positions in the company. As can be seen from the chart below, in 2020 (unsurprisingly) the stock underperformed the US REIT Index significantly. However, in January there was a significant but extremely short-lived blip where the share price doubled before returning back to its previous trading range. What happened, and why does it matter for the company?

“You have to be nimble in raising equity capital, otherwise there is a significant risk of being crowded out”

The answer is as follows: the share price rose sharply because the company was landlord to GameStop, the retail gaming company that was the centrepiece in the war between hedge funds which shorted the stock and retail investors who drove the price up. If a fund shorts a stock, it can only close the position by buying. When the price started rising, the funds had to try and buy to minimise their losses, thus pouring rocket fuel on the fire and increasing the price rises.

So when the Reddit-based army of private investors grew weary of 100% per day gains in GameStop, their interest moved on to other companies that were related to GameStop and where funds had a short position. Enter Macerich. In the last week of January the share price spiked. As a result the company started discussing the possibility of an opportunistic equity raise to capitalise on its newfound popularity. However, its largest shareholder – the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan, which owned 16.4% – had other ideas. They had seen the price rise and decided to take the opportunity to sell their entire stake to a tsunami of retail investors and hedge funds. As a result, supply suddenly equalled demand – equilibrium was restored, and sadly for Macerich it didn’t achieve its opportunistic equity fund raise. The whole episode was over in days.

Moral of the story: equity markets can have very significant price dislocations unrelated to fundamental value, but these do not last long – and never forget that existing holders can often be quicker off the mark than a corporate issuer.