This article was originally published in October 2017.

In a conscious echo of Harold Macmillan who oversaw the construction of more than 300,000 mostly local authority houses in 1953, the Prime Minister recently announced that her government is ‘getting back into the business of building houses’ by allocating £2 billion towards new affordable homes. Commentators were quick to point out this will finance just 25,000 additional properties against a manifesto commitment of 1.5 million new homes over the next five years. Nonetheless, the announcement marked a shift in emphasis from a party that has consistently advocated owner occupation for more than a century. During this time, owner-occupancy rose from just 23% in 1918 to a peak of 71% (in England) in 2003. This article briefly outlines some of the drivers of changing patterns of property tenure since the late nineteenth century.

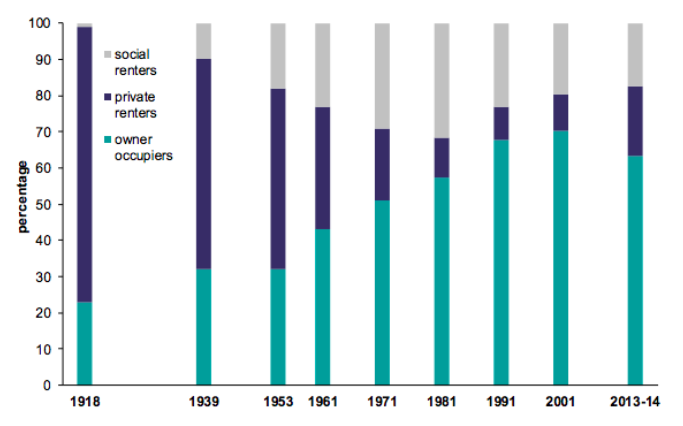

Figure 1: English property tenure since 1918

Source: English Housing Survey, 2013-14

Before the First World War, more than three-quarters of households rented from private landlords. These ‘housing capitalists’ were nonetheless on the defensive as the burden of rising local authority expenditure fell largely on the rates. Landlords received little support from a Conservative party dedicated to defending the propertied interest by creating a ‘rampart of small proprietors’. Given the distribution of tenure, this had to be at the expense of private landlords.

The attractions of property capitalism further declined with the 1915 Increase of Rent and Mortgage Interest (War Restrictions) Act which increased tenants’ security of tenure and froze rents at pre-war levels – this at a time of rising wartime inflation. The 1915 Act also capped mortgage payments, reducing the attractiveness of property lending as an investment class. Rent restrictions were extended after the war such that by 1931, 69% of homes in England and Wales were subject to rent control. This reduced demand for new building for the private rental market.

While there was some liberalisation of rent controls in 1933, the 1930s housing boom, described in these pages by Tehreem Husain, was primarily an owner-occupier phenomenon, financed by the building societies and very much in sympathy with the Conservatives ‘rampart’ strategy. Most of the other new homes were built by local authorities, mandated to provide social housing by the 1919 Housing, Town Planning, &c. Act. Here there was a clear political divide between Labour governments, committed to subsidised local authority housing, and Conservatives who viewed social house building as a short-term expedient, best directed towards slum clearance, that entailed redistribution of resources from their core supporters to the least well-off. The interwar housing market was therefore characterized by building society-financed housing for the middle classes, and taxpayer-financed housing for the working classes. As Figure 1 shows, this squeezed new building for private rentals which remained the largest sector (58%) at the outbreak of World War Two only because of a previously dominant position.

The pattern established during the interwar period continued until the 1980s, aided by the taxation system. Until 1963, owner-occupiers were taxed on the imputed value of living in their own homes (‘Schedule A’). This was predicated on the assumption that owners could rent out their homes if they wished. Failure to do so indicated that the value of occupancy must at least equal the rent foregone. But the imputed tax liability was often based on rent-controlled values and could be offset by mortgage payments, repairs and improvements, even to the extent of generating a loss that could be set against income tax. This option was not available to tenants, nor was it as attractive to private landlords who had less incentive to reduce their net income by improving their properties. The fiscal system was further tilted towards owner-occupancy with building society deposits taxed at a lower rate than income, providing the societies with funds to lend on mortgage. Finally, capital gains tax, introduced in 1965, has never been applied to principal residences.

Schedule A was abolished in 1963, but the ability to offset mortgage interest against tax remained in one form or another until 2000 for owner-occupiers (and still remains for private landlords, albeit in attenuated form). Higher rates of income tax, lower real tax-free allowances, rising incomes, and higher interest rates combined to increase the value of this subsidy for owner-occupation, especially during the 1970s and early 1980s. Offsetting mortgage payments against tax during this period of high inflation reduced the cost to the homeowner of acquiring additional equity value in the property. In many ways, it has been irrational for those who could afford it not to own their own homes for much of the postwar period.

Owner-occupancy stood at 63% at the end of 2016, with a higher proportion of outright owners than mortgage holders. This reflects an ageing demographic profile, with older owners more likely to have paid off their mortgage. Falling owner-occupancy since 2003 has been offset by an increase in private rentals which are back up to 1960s levels at 20%. Social renting has stabilised after a long decline driven by ‘Right to Buy’ council house sales, and currently stands at 17% of English households. This is what makes the Prime Minister’s announcement so interesting. Radio 4’s Today Programme dutifully met the announcement with an audio clip of Harold Macmillan, whose 300,000 target was also adopted in haste to see off a rebellion at a Conservative party conference. And, while it is unlikely that the state will once again take responsibility for building more than half of new homes, there may be broader implications. As Cambridge historian Martin Daunton points out, ‘a nation of owner-occupiers has very different social and political implications from a nation of tenants’.