The Director, Real Estate Research Centre, The Business School (formerly Cass) looks for an answer.

The two most common phrases at the moment are: 1) “Can industrial yields really go much lower?” and 2) “Retail values must surely be close to the bottom” (having fallen 60% from the peak in capital value terms and 40% in rental value terms). The premise behind both sets of comments is that the (sub)sector is cyclical and that eventually some form of mean reversion will occur, and capital values and rents will magically converge back to a prescribed ‘fair value’.

There are a number of factors to consider here, namely:

Are markets currently responding to cyclical or structural changes, and is there a difference between the public and private markets?

What could be the catalyst for such a change and what would be the first signs of it?

Does current pricing take into account rental growth prospects and, possibly more importantly, future CapEx requirements?

It could be argued that modern regional UK shopping centres had a 40-year positive run from the opening of Brent Cross in 1976 until 2016.

Unlike their cyclical counterparts – offices – they were regarded as a positive long-term generator of total returns. However, this all ended in 2016, when the market started to ‘decouple’ in terms of sector performance. This is now finally being reflected in property valuations as seen by the latest results season, but given the leading indicator nature of the sector, the easiest way to illustrate this is by looking at the share prices (not total returns) of the key sectors. (See Table 1).

For simplicity I have chosen one company (the largest by market capitalisation) per sector. The starting point is June 2016 – not because it conveniently happens to be five years ago, but because it represents both a previous peak to the market and an unexpected (to many) catalyst in the form of the EU Referendum result.

Chart 1. Sector proxy performance: divergence not convergence

Source: Bloomberg

In fact, looking at chart 1, you would be forgiven for thinking these were completely different asset classes (gold, US Bonds, tech stocks and retailers, for example), not the same sector. Over that period the best sector proxy (Segro) would have generated a 2.5 x return (enough to keep most PE funds happy), while the worst (retail) would have somewhat inconveniently wiped out 86% of your initial investment, or in the case of Intu, 100%. Therefore, it’s easy to argue that the change is structural and sector specific. Unlike previous positive major inflection points, there is unlikely to be a broad sector based rebound for the very obvious reason that the different sectors are priced and valued very differently in both public and private markets. Therefore (sub)sector allocation based on these structural changes, as well as an accurate assessment of CapEx requirements and management capability, will remain crucial going forward.

Typically catalysts for significant changes in capital values have been: interest-rate led (positive in September 1992, negative in the Taper Tantrum of May 2013), country specific (impeding UK REIT legislation in 2006) or market driven (GFC 2007-9 and subsequent QE led recovery). However, interest rates are at all-time lows, so any inflection points are likely to be negative for the keenest priced assets. The sector cannot be viewed as one in terms of equity market weightings, so there is unlikely to be a dramatic change in global allocations to listed, although the allocations to direct continue to mount, with a dry powder glut of epic proportions seeking deployment on suitable assets. The most obvious leading indicator would therefore appear to be changes in sentiment leading to changes in allocations leading to changes in market pricing. How can we spot this in advance?

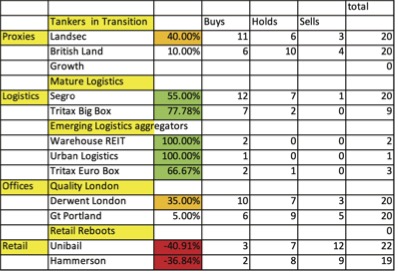

One (of the many) leading indicators we use is to monitor changes in analysts’ recommendations. These can change overnight to reflect events and typically presage an eventual change to forecasts. The way we look at it is to divide the sector into different categories. Table 1 shows a small example of some of the clusters that we can identify for the UK REITs. We then use Bloomberg to take the number of buy, sell and hold recommendations, and assign a +1 for a buy, 0 for hold and -1 for a sell. The total is then divided by the number of analysts covering the stock to give a % favourable rating.

As can be seen, the companies in each cluster have a broadly similar strategy/asset mix. British Land and LandSec are two of the largest REITs, and are both busy reorienting their business models and asset allocations away from unwanted legacy positions to a more robust portfolio to meet current market conditions, thus we term them ‘tankers in transition’. Here there is likely to be a reasonable level of company specific performance based on the successful execution of their strategy. Similarly, at the other end of the scale, we have the retail landlords (retail reboots) who are seeking to manage the transition to omni-channel retail and mixed-use schemes, while again jettisoning some legacy assets. We therefore monitor the recommendations of these two groups to determine which is receiving a more positive reception from the analysts, as they are currently more alpha than beta plays.

For the mature logistics plays it is really a question of monitoring when sentiment towards their sector may start to abate, ie, the change in the allocations trade. For the newer and smaller logistics plays, we are monitoring how the analyst coverage expands and how they manage to optimise asset aggregation with shareholder returns. For Quality London the companies have impressive track records and it is again trying to determine how successful their strategies of managing the challenges of WFH are being received.

Table 1

Finally, we would make the point that in the current environment, where income is more uncertain, repositioning and upgrading assets is essential and operational management skills crucial, there is a tendency to underestimate both a) the capital expenditure required to achieve the desired returns and b) the extent to which any reversion to ‘fair value’ is likely to be specific to the individual asset rather than the sector as a whole.