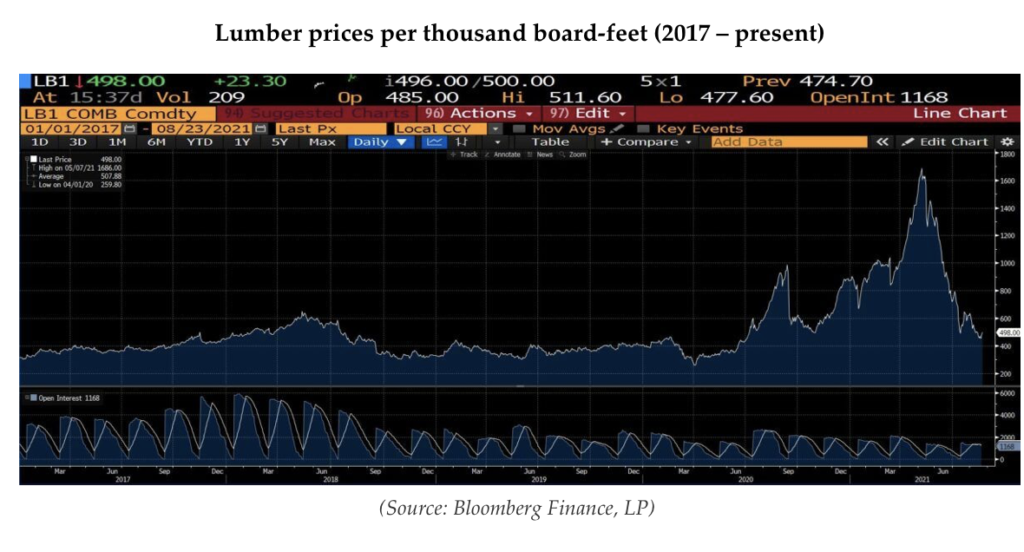

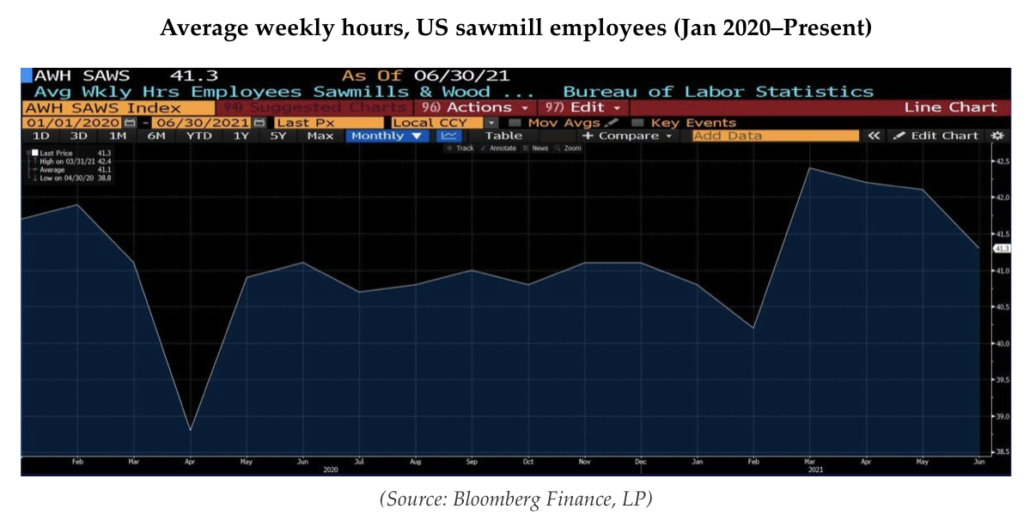

It was inevitable that lumber prices would eventually return to some state of normalcy. I wrote an article less than 50 days ago noting that futures and cash prices, despite having quadrupled in slightly over a year, had dropped 40% in June 2021. Pandemic measures were being lifted, the effect of stimulus payments were receding, and owing to completion or returning to work, home improvement projects were wrapping up. High prices, as they do, drew more wood into the market; mills increased weekly hours for sawmill employees and substitutes for timber, whether different types of wood or composites, were used where possible.

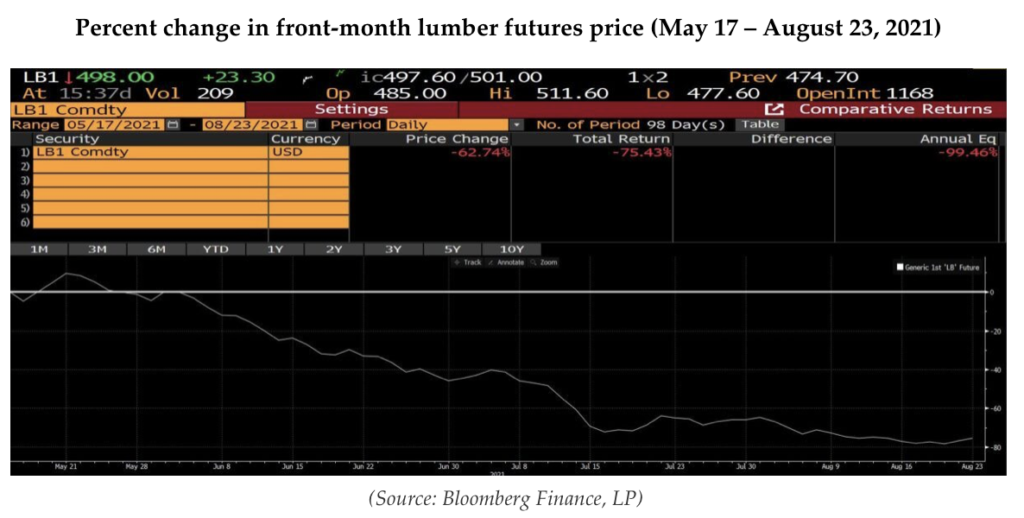

But over the past week or two, the delirium which began in the summer of 2020 and reached a crescendo in April and May of this year has been utterly inverted. A late July 2021 poll reported that 49% of lumber dealers were suddenly reporting excess lumber inventories. And whereas in April 2021 40% of lumber dealers had reported low stocks, in late July/early August none of the respondents indicated such.

Lumber prices have fallen 75% since the all-time high of $1,686 per thousand board-feet on 7 May 2021. All the price gains since the summer of 2020 have been given back, and at under $500 per thousand board-feet, the front month futures price is actually below the average price of lumber back to 2017.

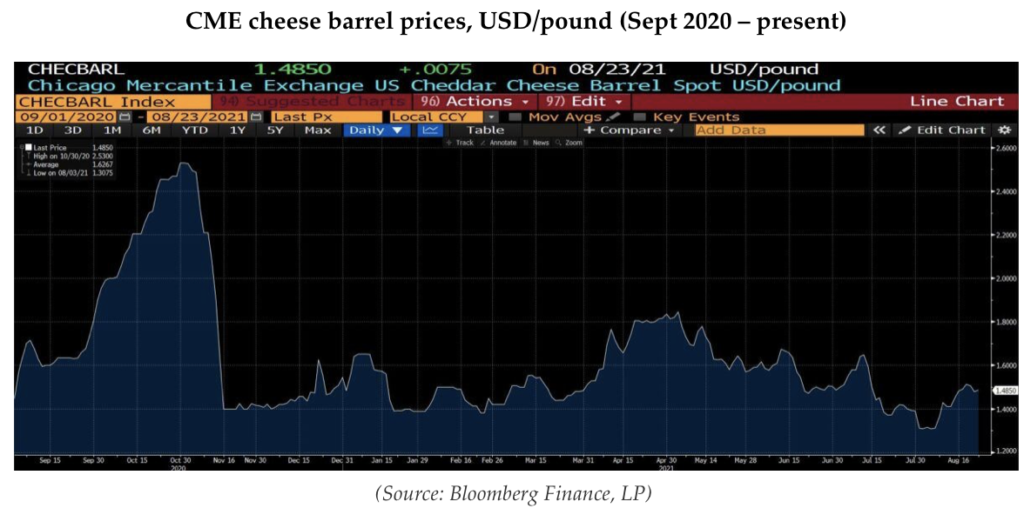

(A particularly unexpected consequence of the volatility in lumber prices has manifested within another typically staid arena: the Chicago spot-call cheese markets. There are two major cash cheese markets: one calculated on the basis of blocks, the other on barrels. The price of wood is a major input into barrel prices; thus when scarcity took hold and lumber prices burst to record levels, cheese producers shifted to processed cheese, which unlike natural cheese can be stored in plastic-lined cardboard boxes. Processed cheese is easier, faster and cheaper to produce than natural cheese, and the price collapse of barrel cheese since September 2020 is a third-order effect of Covid policies.)

Needless to say, the first and second quarters of 2021 were heady times for owners of timberland, mills, and other forestry-related businesses. In mid-July 2021.

West Fraser Timber recorded net income of $1.49b for April, May and June, an amount the company has historically needed years to earn… PotlatchDeltic, which owns timberland in six states and mills in four, said its wood products division was more profitable in the latest quarter than it was during all of last year… Canfor, which operates 10 mills in western Canada and 12 in the US South, followed suit, reporting its own record quarter on Thursday. Weyerhaeuser Co, the largest US timberland owner and operator of mills in the US and Canada, said it had its most profitable quarter ever by 40%, with net income of $1.03b.

But many of those same sawmills that saw record earnings in the first half of 2021 are suddenly in the red. To get an idea of exactly how inundated dealers and wholesalers of wood building materials have become, late last week the Conifex Timber mill in Mackenzie, British Columbia, announced that owing to the “unprecedented collapse in lumber prices” it would reduce lumber production.

More mills will likely follow Conifex’s lead with additional curtailments in the near future. If not, they will need to decide how much of their first-half 2021 profits can be thrown away while awaiting higher prices. Producers in British Columbia’s key interior region are now ‘underwater’, with regional mill cash costs around $525 to $575 per thousand board-feet in the second half of 2021[.]

To add to this, even a series of wildfires in western Canada haven’t interrupted the downward slide in prices.

The retracement of prices in lumber adds credence to the assertion that much of what has been called inflation over the past six to 18 months may simply be the ripple effects of Covid mitigation attempts. And in turn that those disruptions and distortions will prove transient as supply and demand regroup and align. But that assessment oversimplifies the current set of circumstances.

First: although the prices of certain commodities, goods and services that spiked early on have now declined, others – in particular, financial assets – have remained elevated or advanced further. And second, even though some of those price increases were not inflationary in the monetary sense and (or) prove temporary, the policies which caused anomalous market conditions have nevertheless caused economic damage. Even short-lived government initiatives have an impact upon economic calculation, financial and managerial decisions, and choices regarding the allocation of resources. So, to the extent that pandemic responses generate under- or unemployment, mispricings and other adverse effects, their ephemeral character is scant recompense. (Consider the millworkers who, after joining mills bursting at the seams in April and May, suddenly face reductions in hours, layoffs, etc.)

The spread of the Delta and subsequent variants of Covid may induce more kneejerk policies, which are likely to kick off another round of politically inflicted commercial missteps. Unfortunately, carefully considering trade-offs remains alien to the calculus of public officials. From utter scarcity to crushing abundance in less than 100 days, the lumber epic is entering a new phase.

Originally published by the American Institute for Economic Research and reprinted here with permission.