Kicking good sense out of touch.

For most of us, the pursuit of profit has been the primary driver of our businesses. Recently, a new constituent has emerged in the form of environmental, social and governance considerations, ‘ESG’.

This new ‘stakeholder’ does not have profit as its primary driver. By the Treasury’s own estimate, the cost to the Exchequer of attaining net zero alone will be £1.4tr, without even considering any of the other aspects of ESG. No attempt has been made to assess the additional cost to the economy. ESG is turning business objectives on their head.

The narrative is that, over the long term, risk adjusted returns will increase for those businesses that embrace it the most. However, there is currently no analysis or empirical evidence to substantiate this belief. Nor can there be. But with the legislation being put in place mandating ESG principles we are all going to have to comply.

“To establish the good governance espoused by ESG, good governance is being set aside”

Many institutions and businesses have already hardwired ESG into their organisations, rewriting their profit-focused goals without even a nod towards shareholder consent. These are the same institutions which habitually demand protection for shareholders. To establish the good governance espoused by ESG, good governance is being set aside.

The drive to attain ESG credentials runs the risk of becoming a bureaucratic tick box exercise at the expense of shareholders. It has already created some perverse incentives which undermine its underlying principles.

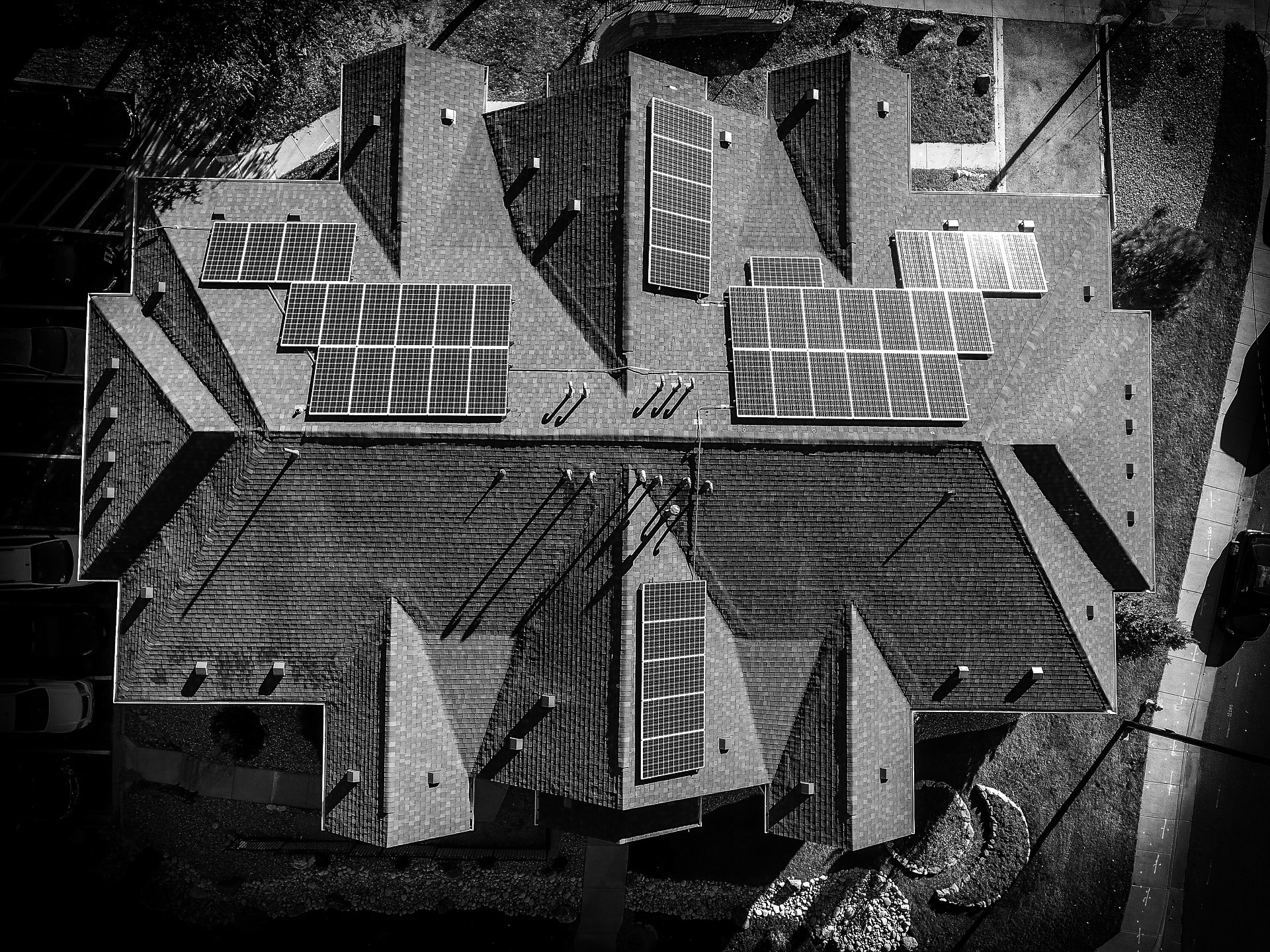

In the commercial property market this is perhaps best illustrated by institutional investors boasting green credentials by citing their investments in highly specified newly developed buildings which incorporate the latest ‘green technology’. Eco measurement league tables encourage the development of such buildings by only judging the end product. On the other hand, buildings with low energy performance certificates (EPC) are discriminated against.

Such a measurement system ignores the cost and carbon emissions resulting from the attainment of high eco ratings. According to the Carbon Risk Real Estate Monitor (CRREM), the carbon footprint of demolition and rebuild is equivalent to 25-50 years of operating a building. The production and installation of concrete and steel are among the most carbon emitting activities in existence. Furthermore, highly specified buildings tend to suffer obsolescence the fastest.

It makes more sense to improve what we already have than to start again. According to CRREM, 60-80% of embedded emissions in existing buildings are reusable. Reuse, recycle and improve! Aside from the carbon impact of demolition and rebuild, the lower financial and social costs of improving existing stock are compelling. But what a hassle that would be. Much easier to tick the box and tick it big with the shiniest, largest and newest Class A building in a prime location.

Measuring success in ESG is not just complex, but ridden with nebulous jargon and bias. You would be forgiven for concluding the current measurements system is self-serving to those who designed it.

Rental values in secondary locations more often than not prohibit demolition and rebuild. And here is the problem, over 80% of the built environment in the UK has an EPC rating of ‘C’ or lower. Over 80% of our commercial buildings are destined to be illegal to rent by 2030, under mooted changes to Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards (MEES) regulations. This equates to over 1.5 million buildings and over 7 billion square feet. It is absurd even to contemplate demolition and reconstruction on such a scale.

But if nothing is done about these buildings, they will fall out of use, exacerbating the social divide between the wealthiest and poorest parts of the country. The areas that will be worst hit are those that most need investment and levelling up. A more pragmatic system which also measures improvements in buildings and how they are used would be better for both the E and the S in ESG.

The implementation of ESG is leading to a buildings’ emergency and with it seriously damaging social impacts.

The application of ESG in the property sector urgently needs an honest appraisal.