Originally published April 2022.

Long-held assumptions about rising house prices are being shattered by the affordability crisis.

When Nigel Lawson described the NHS as “the closest thing the English people have to a religion”, his party was in the process of substituting it with another: the housing market. Policy changes such as tax incentives, the right to buy and the deregulation of the private rental market had formed the basis of Thatcher’s goal for a “property-owning democracy” and for decades the narrative has held that rising house prices translate into general wealth.

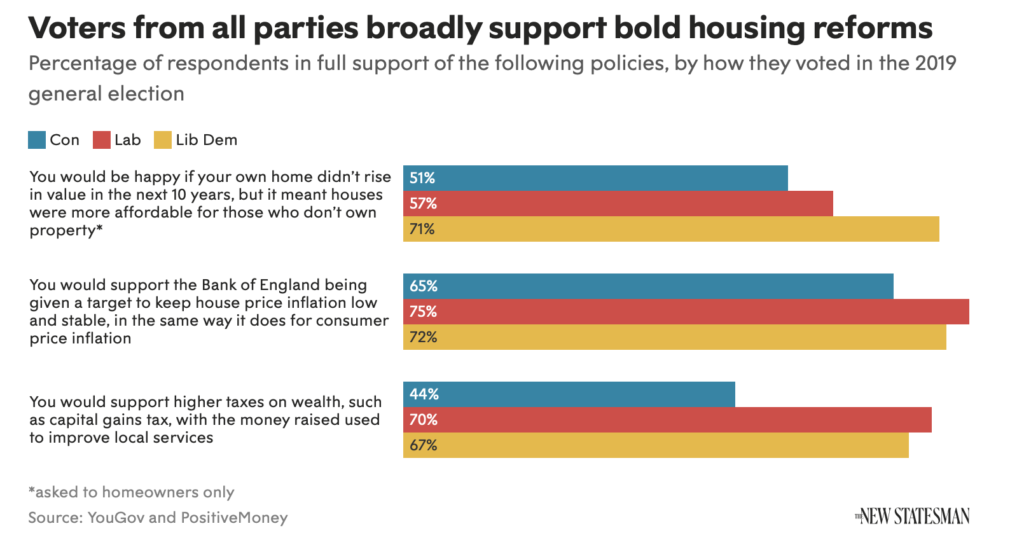

Polling released yesterday (31 March) indicates that the British public no longer believe this story. Confronted by low levels of home ownership and an affordability crisis, the British public would now prefer house-price growth to remain low or to stop entirely, and homeowners are in favour of bold reforms to make housing more affordable at the expense of their own properties increasing in price.

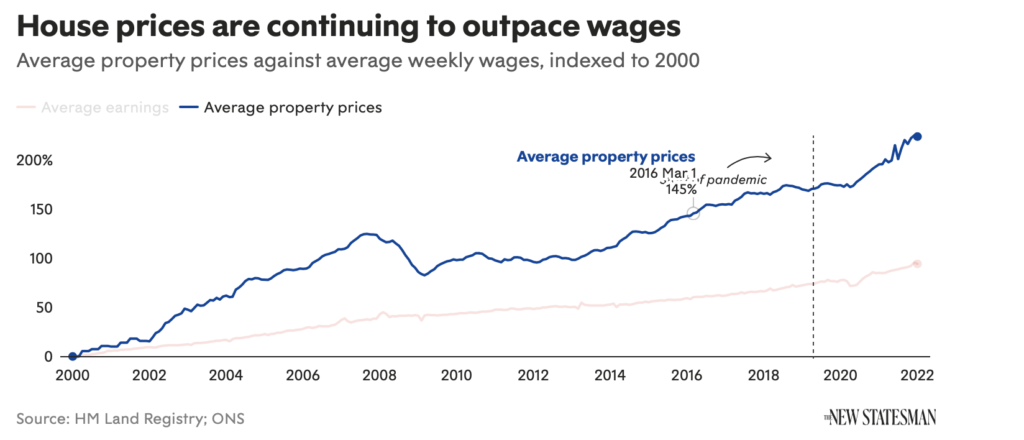

The polling, carried out by YouGov on behalf of the research and campaign group Positive Money, found that more than half (54%) of British homeowners would be happy if their own home did not rise in value in the next 10 years, if that meant houses were more affordable for those who don’t own property. Since 2000, average wages have grown by 94% while house prices have grown by 224%.

“I think people realise that the system is broken when you can’t really own a home just from having a job,” said Danisha Kazi, senior economist at Positive Money. “Soaring house prices are locking the younger generation out of home ownership. Most people who own homes are older, they’ve got children or grandchildren and they recognise there isn’t an easy way to get them on the ladder other than for them to give them equity that they have in their own housing.

“At the same time, many homeowners are also banking on their own house paying for their retirement or care — the costs of which are also rising — and many are not wealthy enough to pass housing wealth on to their children.”

The realisation that rising house prices do not create prosperity even for wealthier homeowners means that support for reform comes from a broad range of demographics. A majority of Conservative voters would be happy if their home didn’t rise in value if it meant others could buy, and would support the Bank of England being given a target to keep house price inflation low and stable. Similarly, 44% of Conservative voters (and 51% overall) would support a rise in council tax for owners of homes above the national average house price and a decrease for those with homes that are lower.

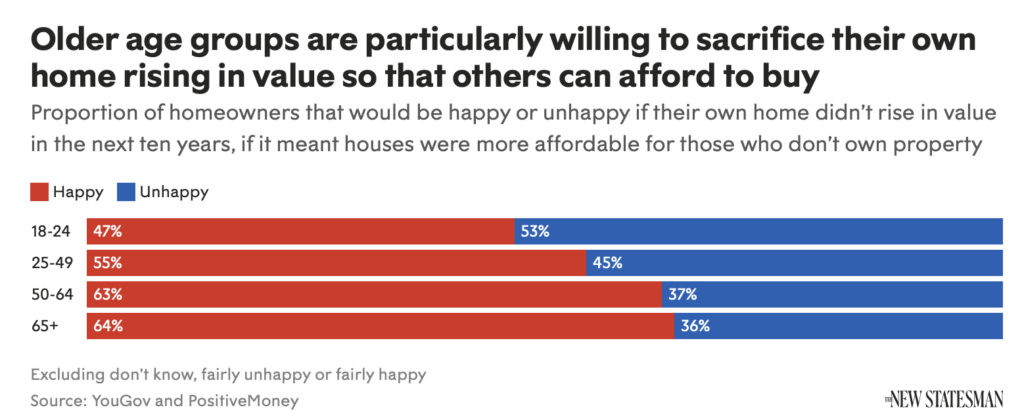

The poll found that older voters were actually more prepared than any other age group to sacrifice rising value on their homes in favour of affordability, perhaps because they are less exposed to the risk of falling prices, having built up more equity. The Conservatives had a 62% share of the over-60 vote in the 2019 general election.

The report also counters the common assumption that the housing crisis is primarily the result of a shortage of homes. It reveals that new supply has in fact exceeded the formation of new households in recent decades. In 2020 there were 7.5% more dwellings than households in London and 4.8% more in the South-East.

Home ownership in England peaked at 71% in 2003 and has since fallen to 65%. For young adults it has fallen more sharply, to 47%, while home ownership among ethnic minorities is lower still, at 35%.

High rents and the change in working patterns caused by the pandemic have exacerbated the problem: 42% of private renters say that the pandemic has made home ownership a more important aspiration for them, while 68% of all renters don’t believe they will ever be able to afford a home of their own, according to Ipsos Mori polling.

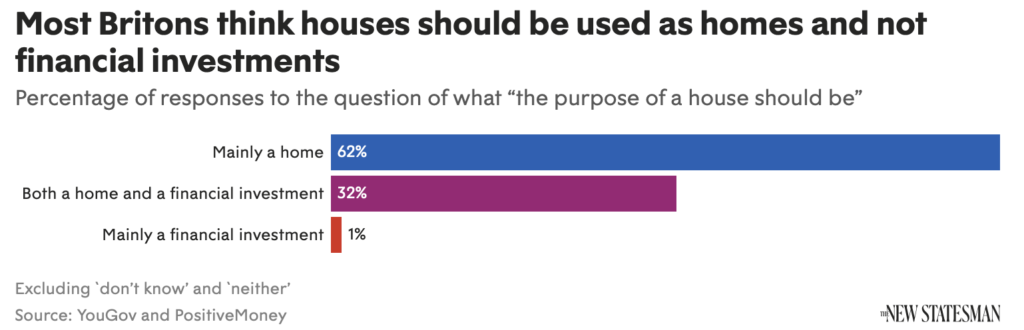

Years of policies such as help to buy, changes to stamp duty, the shared ownership scheme and extended mortgage terms have only served to financialise Britain’s housing market, a problem most voters now apparently recognise: a large majority believes that the purpose of a house “should be mainly a home, not a financial asset”.

While the UK’s housing affordability crisis is particularly severe, rapidly changing attitudes on housing have already proved electorally significant in Sweden, where rent control policy led to a government crisis; in Ireland, where housing has been a key issue in the resurgence of Sinn Fein; and in Canada and New Zealand, where governments have taxed or restricted foreign buyers. British voters, too, seem hungry for new ideas.

Originally published by The New Statesman and reprinted here with permission.