This article was originally published in December 2017.

We all know the first and most basic lesson of economics: incentives matter. This is surely why, as a new investigation by The Guardian has revealed, fires in the favelas of Sao Paulo are happening where land values are greater.

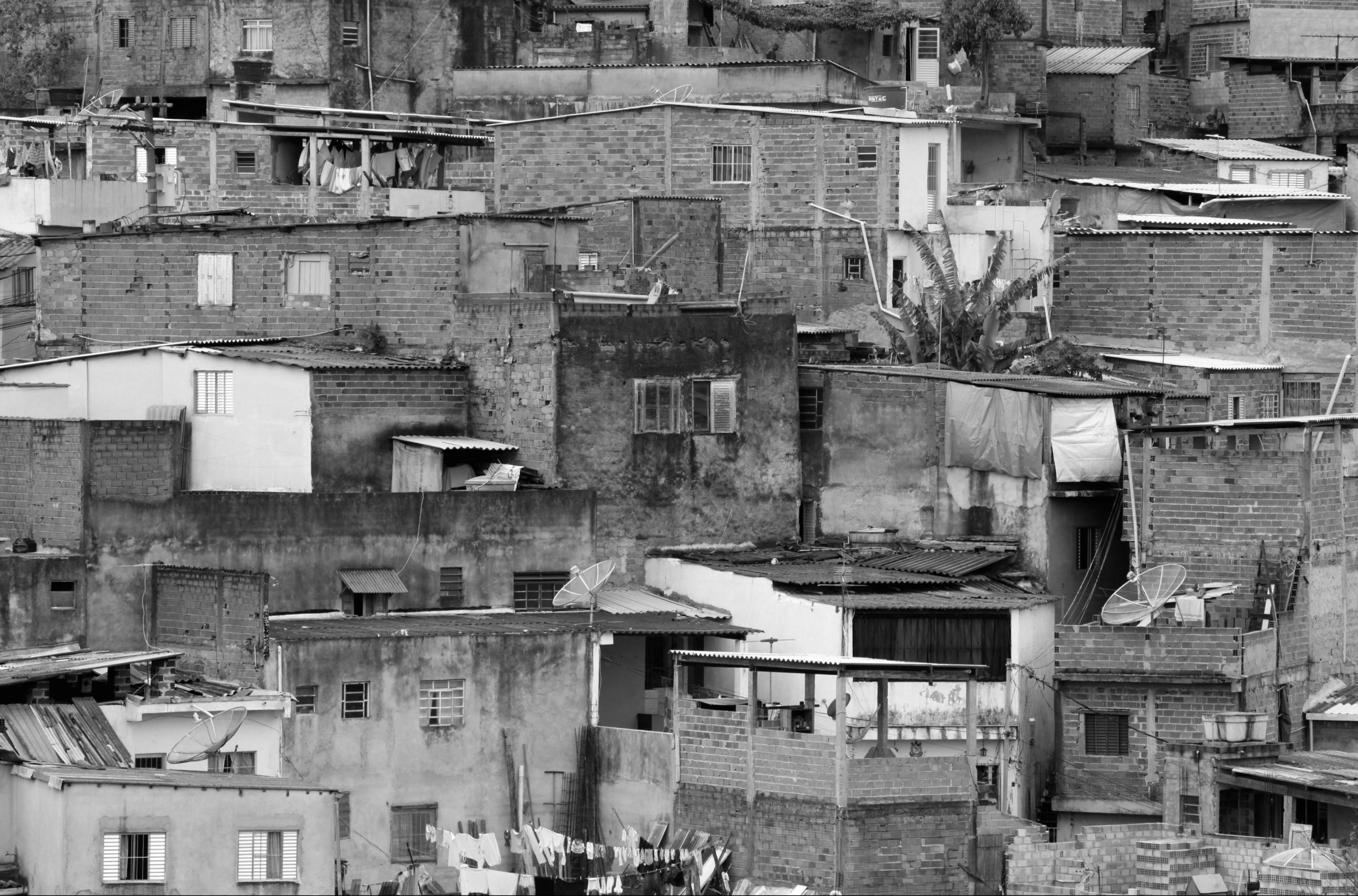

It’s true, as the authorities would have us believe, that those urban slums are built largely of wood with a treacherously hotchpotch electrical supply running through them – and it’s no surprise they so readily catch fire. But the underlying problem here isn’t one of unregulated building, it’s the absence of – the non-regulation if you like – property rights. That is why there are more fires where the land is of higher value.

Hernando de Soto has spent decades pointing out that these slum dwellers have perfectly valid de facto property rights to their shacks. What they don’t have is any de jure rights. This means, as de Soto points out, that they have capital but cannot leverage it.

But if you were to allocate those de jure property rights to those who have them de facto then the poor would have capital and would, through the normal workings of markets, end up being very much richer – huzzah! Not only that but once their ownership were formalised, they would also gain access to utilities such as sewerage, clean water and non-life-threatening electricity supply.

A fire, though, is a great way of wiping out those de facto rights and leaving a nice clean development area which those with access to the courts and formal property allocation systems can fight and profit over. Hence why fires are more common in areas of higher land value.

There is nothing specifically Brazilian or Latin American to this problem. We’ve seen something similar in Europe, in both Portugal and Greece. Forested land has, to some extent at least, been protected. You may not chop down the trees to build houses. However, the law has said that if something unfortunate like a fire were to take the plants, then there would be a presumption of planning permission on that newly not forest area.

You do not have to have petrol can and matches in hand to see the incentives here. And, remarkably, forest fire incidence in both places fell when the presumption of being able to build in the wake of such an event was abolished. Specifically, it fell in those desirable areas where people might like to build villas, and didn’t change out in the boonies where no one wanted to do anything at all.

The change in incentives left us with a naturally occurring level of fires. Humans, you see, do react to incentives. Remove the incentives for fires and there will be fewer fires.

Brazil is far more unequal than any part of Europe. The poor there are a great deal further away from the rich than they are here. But one of the reasons for this is a system which just doesn’t allow nor enable those poor to own in law what they do in fact own. Sort out the allocation of property rights and both they and the society itself will be richer.

And, of course, fewer shacks will burn down when third parties are no longer be able to profit from their having done so.

All of which is rather the inverse of Anatole France when he said: in its majestic equality, the law forbids rich and poor alike to sleep under bridges, beg in the streets and steal loaves of bread. Quite so. But it is also true that the majestic equality of the law, where it actually exists, protects the property of the poor rather more than it does that of the rich.

Or, as de Soto has been arguing all of these years, proper legal protection of property rights is one of the most pro-poor economic policies we have.

This article was originally published by CapX and is here republished with permission.