Global housing markets face a potentially significant downturn as rising interest rates, high valuations, and squeezed real incomes start to bite. Risks look especially acute in some markets, where they are already starting to crystallise.

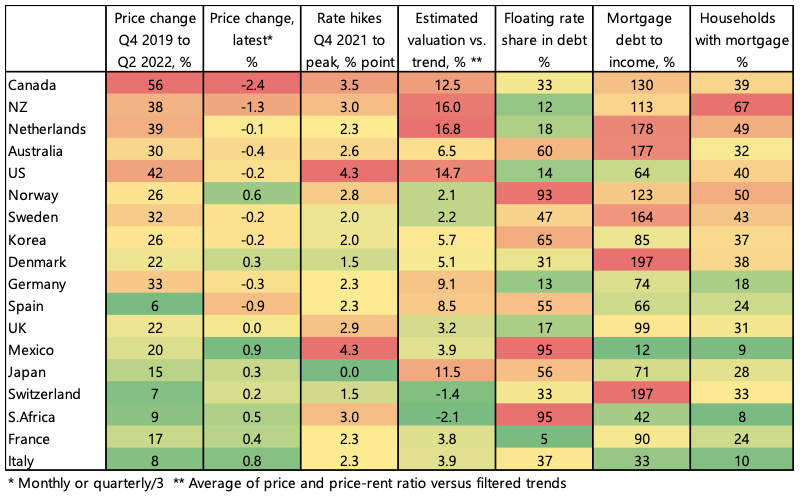

The biggest shift in recent months has been the steep rise in global interest rates, including mortgages. US mortgage rates are now approaching 7% – the highest level since 2002 – up from 3.2% less than a year ago. In the eurozone and UK, we estimate mortgage rates have more than doubled since April and May based on recent movements in swaps (Chart 1).

Chart 1: mortgage rates are surging

Abrupt rises in mortgage rates have strong negative impacts on markets and could inflict a confidence shock on a generation of borrowers conditioned to expect low rates to last indefinitely.

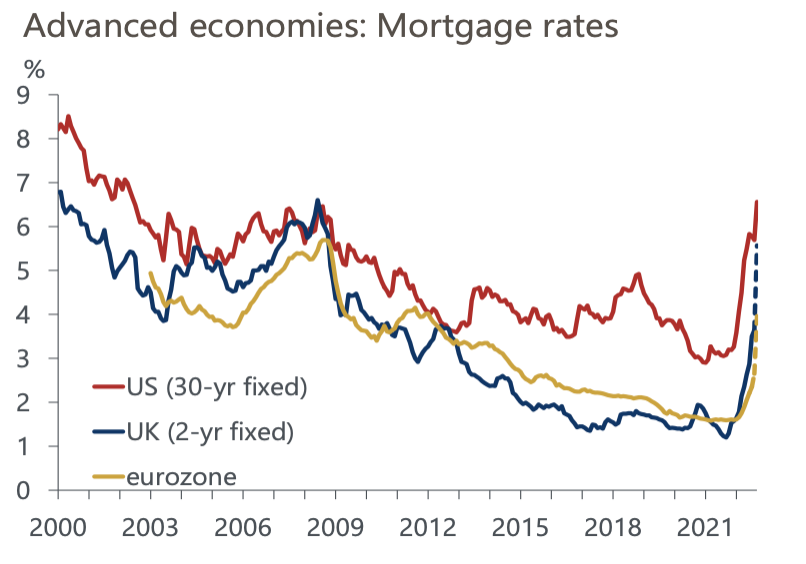

Prices and activity are starting to stumble in several key markets. In the US, the Case-Shiller measure of house prices fell month-on-month in July for the first time since 2012, which is a huge shift of momentum after two years of sharp monthly increases. Meanwhile, mortgage applications have collapsed by a third since the start of this year and are now well below pre-pandemic levels (Chart 2).

Chart 2: US house prices are starting to drop

Price declines are also visible in other markets. In Canada, which has long been flagged by us as a risky market, prices dropped by around 7% from February to August. In New Zealand, some price measures suggest falls of 5%-6% in the three months to August. In all, the latest data show prices falling in nine of the 18 advanced economies we monitor and data lags probably mean that prices are dropping in most.

House prices are also coming under pressure from tightening bank credit standards. On average across the US, eurozone and UK, a net 16% of banks tightened mortgage credit in the latest surveys. This negative balance looks likely to get a lot bigger, given recent rises in global interest rates and declines in broader asset values.

The historical link between movements in credit standards and real house prices in advanced economies is strong, and prices are already reacting to the shift to tightening standards (Chart 3). The prospect of even tighter mortgage credit in the coming months looks like very bad news for housing markets.

Chart 3: mortgage credit standards are tightening in advanced economies

Given all that, how worried should we be?

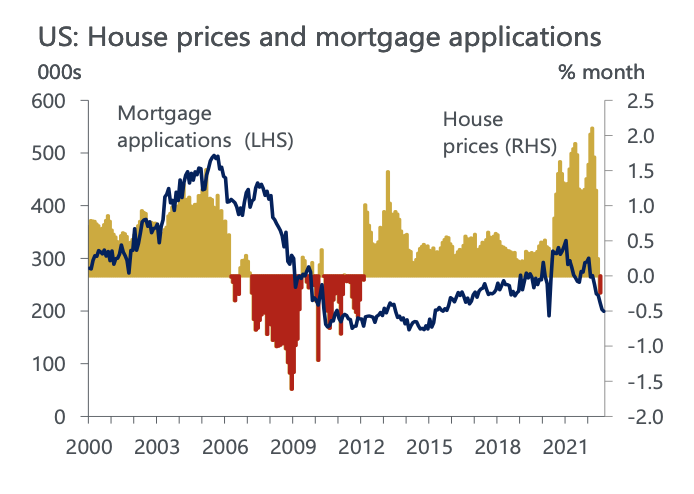

One positive factor is that mortgage debt relative to income in some key markets is lower than it was just before the global financial crisis. In the US, the mortgage debt-to-income ratio in Q2 2022 was 35ppts lower than in Q4 2007, in Spain it was 25 ppts lower and in the UK 14 ppts lower.

But the situation is different in other markets, where a large volume of additional leverage has built up since the GFC. Rises of 25 ppts or more are visible since Q4 2007 in Australia, Korea, France, Canada, Sweden, Switzerland, and Norway (Chart 4).

Chart 4: some markets have deleveraged, others leveraged up

Meanwhile, a steep real estate downturn is under way in China. House prices are down around 8% from their peak of a year ago and residential housing starts have halved.

Overall, the outlook for housing markets looks the most worrying since 2007-2008. In our view, housing markets are teetering between the prospect of modest declines and much steeper ones of 15%-20%.

One key factor determining which of these scenarios plays out is unemployment. While unemployment remains low, the chance that price downturns could be limited is reasonable. Instead, markets may ‘freeze’ at low levels of transactions.

But as recessions bite, unemployment will start to increase, raising the risk of a wave of forced sales and foreclosures, where steep discounts are common. If unemployment were to rise sharply, the dangers to housing markets would be amplified considerably.

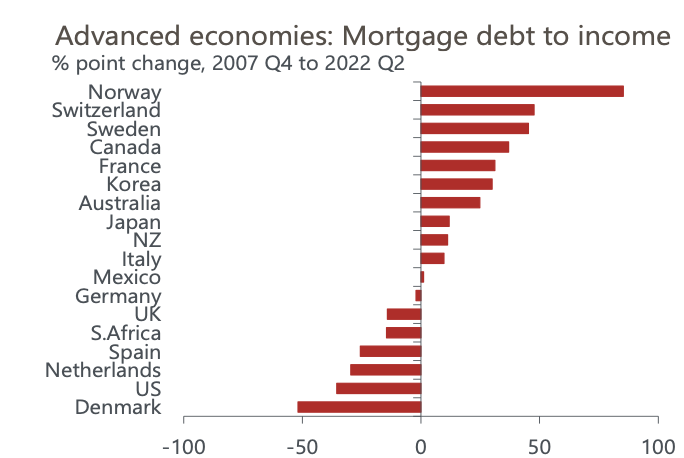

Other important determinants for house prices include: exposure to floating rate mortgage debt and fixed rates resetting at much higher levels; housing valuations; debt levels; and recent price trends. Looking across a range of risk indicators covering these factors, we can see that risks to global housing markets generally have risen, although they vary considerably across economies.

Canada, New Zealand, the Netherlands, and Australia look most at risk. In these economies, price rises from Q4 2019 to Q2 2022 were generally high, valuations are elevated, debt levels are high, and floating rate debt is prominent so that rising interest rates will quickly pass through to household finances. In all these economies, prices have also already started to fall.

The US also looks at risk given very high recent price rises, the particularly steep rise in borrowing costs, and elevated valuations. Offsetting factors include a low share of floating rate mortgage debt and more modest debt levels than in some other markets. We recently estimated that a 15% fall in house prices in the US over four quarters would wipe out two-thirds of the housing equity accumulated since the start of the pandemic.

Markets less at risk include Japan and European markets like France and Italy. Recent price rises in these economies have generally been more modest, valuations look less elevated, and debt levels are lower (Chart 5).

Chart 5: Housing markets ranked by risk factors.