The first James Bond film exploded onto our cinema screens way back in 1962,

but a closer look at this classic can help explain the enduring appeal of one of

the world’s most famous fictional characters.

On the 5th of October 1962, the James Bond film Dr No went on general release across Britain and a glamourised world of jet-setting, suave, secret agents was revealed to the public for the first time. Having only just emerged from black and white, post-war 1950s gloom, the people who went to see Dr No that year were taken to places most of them knew little about, let alone had any personal experience of, and it was all presented to them in luscious, opulent colour. The members only clubs, posh hotels and white sand beaches of the West Indies, the London casinos where independent women casually ask for another £1,000 credit with which to gamble (in 1962, the average annual salary in the UK was around £800), then decide to make a strange man theirs for the night, the hidden offices of MI6 furnished with red leather armchairs, mahogany desks and oil paintings – all were glimpses into the lives of a moneyed elite and the shadowy Secret Service who guarded the British state. Dr No was a very good thriller, yes – a pacy spy yarn full of self-deprecating, tongue-in-cheek humour, but it was also an education, a travelogue and an adventure for the audience. In 1962, no one had seen anything like it before.

What most of the public didn’t know at the time was that the substance of the early Bond films was pretty authentic. Ian Fleming had worked for British Intelligence during World War II and knew plenty about dirty tricks, gadgets and Eton-Cambridge educated toffs who could transform themselves into ruthless killers in defence of their country. In Adolf Hitler, they had faced the ultimate super-villain. The image of Bond as a wealthy, bow-tied sleuth-enforcer (an inversion of AJ Raffles perhaps?) who wore a shoulder holster under his dinner jacket, personified the twin strands of this character type. 007 knows about Saville Row tailoring, vodka martinis, Dom Pérignon Champagne and chemin de fer, but he also carries a gun with a silencer. It is an assassin’s weapon: covert, underhand almost and chilling. In Dr No, even when one of his adversaries has run out of ammunition and is no longer a threat, Bond kills him anyway. This is war and he’s merciless. Because he has a ‘license to kill’ he is beyond the reach of the law.

“The Vatican thought the movie ‘…a dangerous mixture of violence, vulgarity, sadism and sex…’”

But not everyone was enamoured by our Jamess’ arrival on the silver screen. The Vatican thought the movie “…a dangerous mixture of violence, vulgarity, sadism and sex…”, while some film critics were unconvinced by its ability to walk the line between seriousness and spoof. Others were snobby about both Sean Connery and Ian Fleming’s original novels – one critic stating that “agent Bond… is just a great big hairy marshmallow, but he sure does titillate the popular taste…”, before asking, “Is it possible to make a good movie out of a James Bond thriller?”

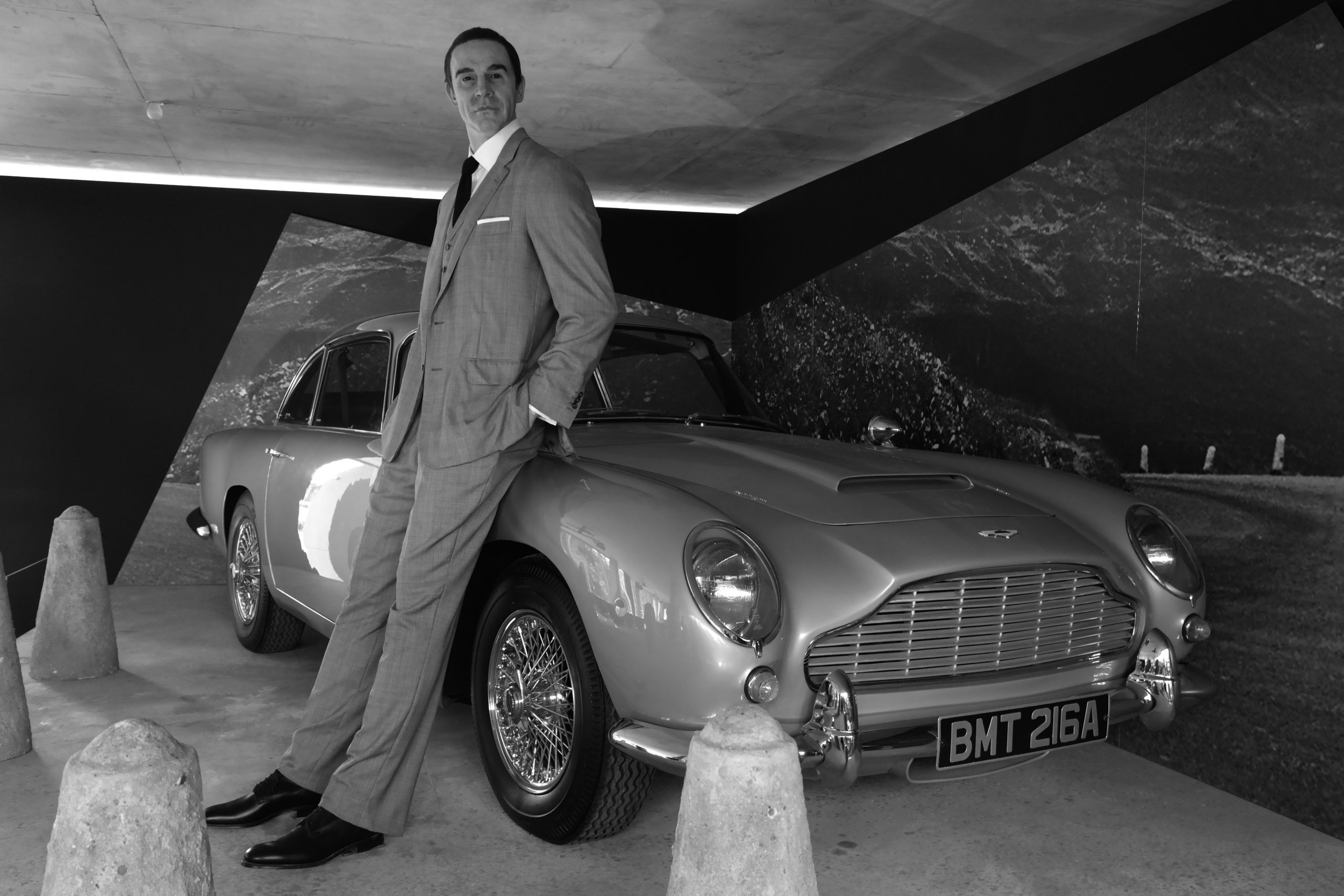

Sean Connery was certainly big, but there was nothing marshmallow about him. In reality he was a tough Scot from a working-class background who’d been a bodybuilder in his youth and after a stint in the Navy knew how to handle himself. This was no weedy, RADA-trained luvvie and his good looks and physicality would help establish the Bond films as box office gold. While heroically loyal, Connery’s Bond is also depicted as a maverick. Both Ian Fleming and his alter-ego, Bond, were a combination of the dutiful and the outsider; the lone wolf pushing back against a system if it tried to make them conform too much. Ian rebelled against his family’s pressure to go into banking by working instead for newspapers and taking to writing. Early on in Dr No, we’re shown Bond’s unwillingness to do what he’s told – he has to be forced to give up his handgun of choice (a Beretta, the gun Fleming himself carried during his time in MI6) and take the Government standard issue weapon instead. It’s a theme which, once established in Dr No, will run through all the subsequent 007 films. He’s nobody’s man but his own.

Add in a megalomaniac bad guy, futuristic sets (designed by former Modernist-influenced architect Ken Adam), including Dr No’s subterranean lair from which Bond escapes through a maze of hi-tech building service ducts (how ahead of its time is that?), a terrific music score by John Barry and Monty Norman, and a masterclass in taut, economic direction by Terence Young (a former wartime tank commander), plus topical references to the nuclear threat, reactor meltdown catastrophe and moon shots launched from Cape Canaveral, and the film’s formula and that of its sequels is complete.

“It ended up being the fifth most popular film of the year in the UK”

Whatever the sniffy critics and some religious groups may have said about Dr No on its release, the public and the majority of reviewers loved it and it ended up being the fifth most popular film of the year in the UK. The promiscuous, risk-taking, irreverent and free-spited Bond would take the public with him into the permissive, swinging 60s. In the US, President Kennedy requested a private showing in the White House. Estimates indicate that while the movie cost only $1,000,000, it took six times that at the UK box office in its first year. So how does Dr No compare to the subsequent 26 Bond outings in terms of monetary success? Well, gross box office takings is one indicator (the more recent films rake in billions), but income against money spent making the film is perhaps more meaningful. If ROI (return on investment) is the real measure of success, then according to research by the Hollywood Reporter and the online James Bond Dossier, Dr No is number one – coming in at a whopping 5,857%. Next up is Goldfinger at 4,063% and at the bottom of the league table are Quantum of Solace and No Time to Die (at 157% and 116% respectively); the latter’s performance being explained by very high production costs and the Covid pandemic.

Despite many changes in popular culture, style, fashion and the advance of globalism since 1962, the original 007 offer present in Dr No remained largely unaltered in the subsequent Bond films, ie, that we will be taken out of our day-to-day lives and transported to a half-true, half-imagined OTT world of super-villains, jeopardy and glamour. But is the modern world calling time on the formula and could it be that the brand needs a radical reset? There’s an old adage that every man wants to be like James Bond and that every woman wants to be with him. Time will tell if that remains true.