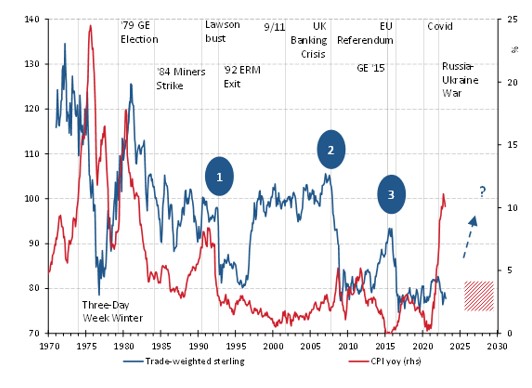

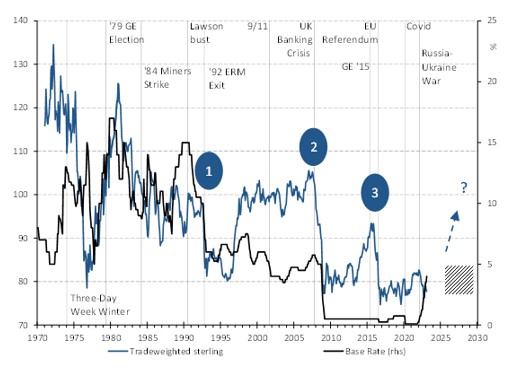

This short piece focuses on Charts 1 and 2. The first maps the path taken since 1970 by sterling, as measured by a trade-weighted index, this charted alongside UK Consumer Price Inflation (CPI). In the second, we see the pound’s eventful ebbs and flows plotted against the UK base rate.

By taking a cursory look at either Chart 1 or 2, one sees sterling’s trade-weighted value starting in the top left corner and ending in the bottom right; a picture, it would seem, of an unrelenting and ‘inauspicious’ fall in the pound’s ‘worth’ of over one-third. Well, inspect the graphs more closely and one notices that much happened between the top left corner (c125) and bottom right (c80).

From the ‘70’s through to ‘87, we see whiplashes in sterling and interest rates, as well as elevated inflation. Then, from around ‘87 until the late autumn of ‘92, a relative semblance of stability reins for the currency, and more moderate inflation, albeit far from entirely modest (Chart 1). These metrics can be seen, however, to have come at the literal expense of high nominal interest rates (Chart 2). This was a period which of course captured (sic) the pound’s imprisonment within the ERM, which, though formally joining in ‘90, it had been a shadowy participant for some three years before, ‘thanks’ to the insistence of the then Chancellor Nigel Lawson.

A mere glance at sterling over the period from Q3 ‘92 cannot fail to put into sharp focus its three sudden plunges. These reflected, respectively, the distinct events of:

- The pound’s sudden exit/escape from the ERM in mid-September ‘92, and the associated marked lowering of the base rate, managed as it was then out of No 11 Downing Street.

- The beginning of the UK’s banking crisis from late ‘07, which saw the base rate cut as dramatically as in ‘92, but this time by Threadneedle Street – the independent Bank of England (BoE) then wisely governed by Mervyn King – an institution which also embarked on a well-judged restorative programme of quantitative easing (QE).

- The “shocking” result of the EU referendum of June ‘16 and the unjustified decision by the BoE – by then in the clumsy hands of Mark Carney – to all the more loosen monetary policy; slashing an already ultra-low base rate and pumping still more QE.

As already noted, on it being unceremoniously exited from the ERM, the pound recorded a sudden sheer drop. Almost immediately after its defenestration, sterling took on the semblance of stability (c85). This was followed by a noticeable rally from ‘97. So much strength in fact that by ‘98, the pound had reclaimed all the ground it had lost on exiting the ERM; the base rate remaining stable. The pound then continued to move gently higher until late ‘07, hitting c105. With the outbreak of the UK banking crisis, sterling suffered another cliff-edge fall. Here again soon after we saw a semblance of stability (c80), then a noticeable strengthening from ‘13, with the currency breaking above c90, until, that is, ‘16 arrived. Markets reacted to the ‘shocking’ result of the UK’s stay or leave EU referendum, by hurtling the pound into a 90° downwards repricing. Thereafter, just as after the shock ERM exit, we see the pound’s trade-weighted value record a degree of stability at c77. This continued through the political travails of ‘16-‘19, then into and out of the COVID crisis of ‘20. In trade-weighted terms, the pound then began to strengthen through ’21; its gentle upward momentum undermined by the energy and food cost shocks caused by Russia’s ‘22 invasion of Ukraine. More recently, one has to note how sterling remained remarkably stable – considering the circumstances – during the playing out of what can only be described as a poorly scripted and generally unamusing political pantomime, and poor directing from the BoE. The history of these three shocks leads me into three observational forecasts, for inflation, rates, and sterling.

- Inflation – a RAPID RETURN TO STABILITY, albeit at a modestly higher new normal of 2-4%

In the wake of the noticeable one-off drops in the pound of ‘92, ‘07, and ‘16, we can see that inflation, certainly its CPI variant, was not lifted in any noticeably sustained way. True, there has been an inflation surge since our being unlocked – when the MPC, in all good sense, should have begun to raise the base rate; a surge spurred on all the more by Ukraine being interloped. This accepted, be in no doubt that in the UK, for all sorts of reasons, the inflation so wildfire in its behaviour in the ‘70’s and ‘80’s has been tamed. So contained, in fact, that there is no reason not to expect a rapid return to a semblance of stability, albeit with a new normal range for CPI of 2-4% (Chart 1). - Interest rates and growth – reasonably higher rates of 3-5%, yes, but POWERFUL REAL GROWTH too

Looking ahead, we should reasonably see a base rate between 3% and 5% as perfectly healthy and indeed long overdue (Chart 2). The base rate being within 3-5% would provide a perfectly respectable real interest rate of c1%, something easily ‘paid for’ by an annual run rate for real economic growth above c2%, a long-term prediction I have long stuck to; the UK epicentre for growth being Central and Northern England – CaNE enabled, as it were. - Sterling – STRENGTH AHEAD

The evidence is incontrovertible. As much as it plummeted in ‘92 and ‘07, within a half dozen years or so of both occasions, the pound managed to begin reclaiming the ground it so shockingly lost (Charts 1 and 2). Why then should we doubt it eventually erasing its sudden losses of ‘16? As for when ‘eventually’ might be, I have no answer other than to point to the fact it took the pound ‘a mere’ five years to reclaim the ground it lost so abruptly in ‘92. With us approaching the 7th anniversary of the pound’s downwards shock of ‘16, maybe the ‘eventuality’ of a sterling rally is closer than so many would have you believe. Indeed, bear (sic) in mind the vast number of sterling bears are the very same forecasters who tried to convince you the UK economy was certain to have gone into recession through last year, and will, from here, measure up very weakly relative to the strength they claim to see coming from the US and mainland Europe. What I happen to see, is the making of one very big bear trap for those shorting sterling and the UK economy writ large.