Recently, I have spotted a not-insignificant-amount of articles accusing younger workers of finding any excuse under the sun to avoid coming in to work.

Personally, I’m someone who enjoys coming into the office – and I’m not the only one – but I have sympathy for fellow graduates and younger people across the workforce who have really fallen out of love with the nine-to-five. As I look at my friendship group from school on social media, I’m surprised by the sheer variety of what they’re up to nowadays.

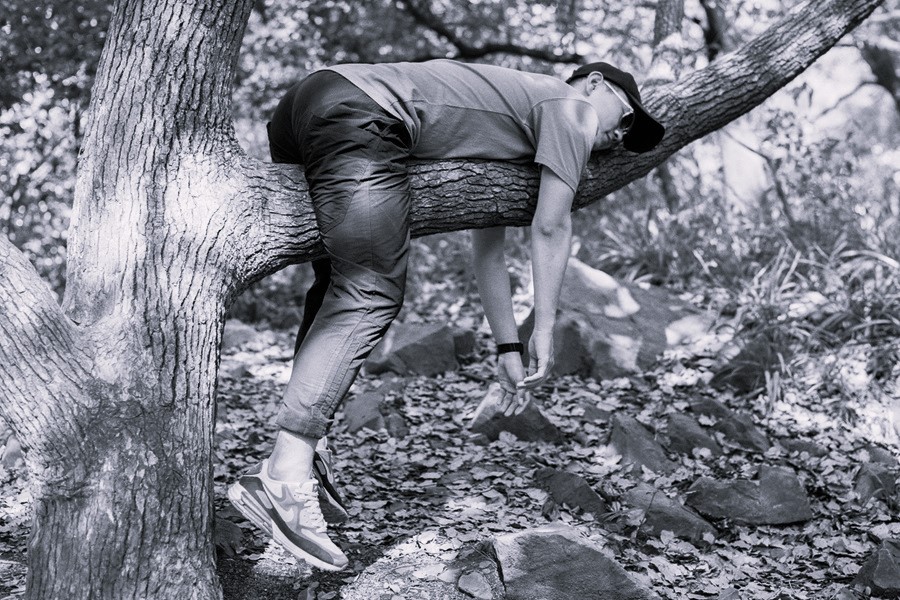

Some have finished university – undergraduate and masters – and are now a year or two into their working lives earning serious money. Meanwhile, some are laying down on a beach in South East Asia, or similar, with no degree but instead a job working at a local bar and an unwavering uncertainty of what they want to do with their lives. The question lies: who’s choosing the right path?

According to official figures, one in five 18 to 24-year olds with mental health issues were out of work between 2018 and 2022, and the number of young people out of work from poor health has doubled over the last decade. To me it comes down to four factors; politics, pandemic, economics and jealously.

Firstly, and arguably the most pressing issue, is the UK government.

As a country, we’re getting to the stage where most young people don’t trust politics. For a lot of us, this lack of trust comes from an innate inability for any party to stick to their campaign promises, sucking all motivation out of younger people who don’t see the point of contributing to an economy where our income tax will be either lost or wasted on pointless policies.

With this, the lack of ambition to solve the housing crisis creates a society of workers who are not working to save money to buy a flat or house, and are instead working to survive. Quite literally to survive. I cannot emphasise this enough; there is little to no enjoyment coming from our work if all our income goes straight to a landlord who likely is sitting on a beach somewhere.

Secondly is the fallout from the pandemic.

From one perspective, people now see life as much shorter. Priorities have changed because, who knows, there could be another pandemic next year that’s even more damaging than the last. We might not ever have the opportunity to travel again.

From another perspective, health has become an increasingly important factor in all our lives. A lot of young people have been seen as fragile, and usually I would agree with that statement. But there is nothing more frustrating than a colleague with a cold, coughing and sneezing on everyone in a tightly packed office, bringing us all down with them, when they could easily work from home instead.

Third is economics; and here comes the collective sigh from everyone reading!

It’s become boring hasn’t it? We always hear it. The UK economy is just trudging along. The combination of economics and politics makes an absolute sh*tstorm.

Is it any wonder, then, that young people have become so frustrated with certain companies hiking prices with absolutely no repercussions? How can supermarkets raise prices during a pandemic because “supply costs more,” yet at the same time announce their record profits without a hint of irony? And how can certain supply companies in a certain UK city which has a monopoly over a certain good required to survive be going bankrupt and passing costs onto us whilst their shareholders are receiving record dividends?

Doesn’t seem fair does it?

Follow up question: why should we work in that system where we are simply being milked for all our income?

Lastly… jealousy.

I’ll happily admit this; I’m jealous of my friends sitting on beach somewhere while I’m sat a desk doing a nine-to-five that doesn’t pay me enough. With social media being a big part of our generation’s lives, I feel like a lot of young people are making themselves ill by thinking that they’re wasting their time at work when they see many others enjoying their lives in exotic countries. The truth is that most young people believe too much in what they see online – working a 9 to 5 is a noble thing, not a waste of time.

To conclude this chain of thought, my belief is mainly summarised in one question aimed at those of older generations: if you were in our position in this economy and political landscape, do you think that you would be motivated to work as hard as you perhaps did when you were younger? I will happily agree with those that think younger people might bunk off for any reason; after all, can you really blame us?