What does it tell you when two of the world’s most cogent cinema essayists decide to put out books on TV?

Mostly, it tells you that there hasn’t been much new cinema to talk about in the last five years thanks to the pandemic and the strikes. More profoundly, it tells you that all the action has been in TV for well over two decades.

Peter Biskind is one of the most pre-eminent film historians with dozens of books on cinema to his name. In his new book, “Pandora’s Box”, he describes the two waves of TV that basically took cinema out, the first led by HBO in the late ‘90s, and the second by Netflix in the 2010s.

Biskind tells the compelling and sometimes shocking story of how HBO reinvented itself, pivoting from sports and comedy specials toward high quality drama. He dates the renaissance from 1997, when it started airing the American prison drama “Oz”. It’s little remembered now, but Biskind argues that without it we wouldn’t have had its more famous successors: “The Sopranos”, “The Wire” and “Deadwood”. All three of these iconic shows are characterised by patient long-form story-telling, nuanced and complex characters, the bad guy as the hero, and a lot of swearing and sex.

Of course, HBO didn’t have it all its own way for long. By the 2010s, the return on investment just wasn’t there with Martin Scorsese’s “Boardwalk Empire” or the even more short-lived “Vinyl”, let alone David Milch’s “Deadwood” follow-up “Luck”. The only thing that saved HBO in this period was taking a chance on two unknown showrunners who wanted to adapt a seemingly unfilmable, sprawling fantasy epic you might know: “Game of Thrones”.

But by this point it didn’t matter to the viewer when HBO had a fallow spell, because the boring, old fashioned cable channels were starting to figure out HBO’s formula. Pretty soon every channel had its own gritty, beautifully produced serious drama.

All of this was not without its problems; the ever-inflated budgets and egos brought with them the typical excesses of corporate behaviour. The detailed way Biskind exposes misogyny, sexual harassment and drug use is both shocking and impressive.

This period for HBO and increasing competition from cable channels came with the second wave of disruption from streaming. Netflix had actually started a streaming service back in 2007 but for at least a decade none of the established content producers thought of streaming as a serious threat to consumption on TV, and they happily licensed out their back catalogues at discount rates, helping Netflix build its audience. Biskind argues that by the time Old Media realised that Netflix was a direct competitor, it was too late: Netflix had already invested in its own hugely successful original content business, beginning in earnest with its remake of the British political series, “House Of Cards”. But it accelerated in the late 2010s with hugely lucrative deals for Old Media showrunners such as Shonda Rhimes and Ryan Murphy who delivered “Bridgerton” and “Dahmer”. Netflix also managed to back newcomers and spot overseas talent, creating hits such as “Stranger Things” and “Squid Game”.

The bidding wars for talent made showrunners rich. But the disruption to the old model of earning residuals from re-runs was broken and the workhouse writers and less famous actors found their earning power diminished. Netflix’s data tells it that four seasons of TV is the sweet spot, after which viewer interest wanes. Well, this doesn’t get you to the magic hundred episodes of TV required for a syndication deal. With the threat Generative AI adds to the mix, it was perhaps unsurprising that we would see a year of strikes in 2023.

The proliferation of streaming services and heavy topline costs have led to subscription fee increases and the reintroduction of ads. Young consumers who had cut the cord to cable are now wondering whether bundled services at a scale discount were really so bad. I note with interest that Disney, Fox and Warner Brothers Discovery have just announced a bundled sports streamer. Everything old is new again!

However, all this has left the humble content watcher with the curse of too much choice alongside too high subscription fees. Many younger consumers have decided to opt out altogether. Why waste time scrolling through your Apple TV menu for a show to watch when YouTube and TikTok can serve you a pre-curated endless loop of short videos? And why have a TV executive spend millions per episode of TV when an amateur with a ring-light and decent upload speed can create the content for “free?”

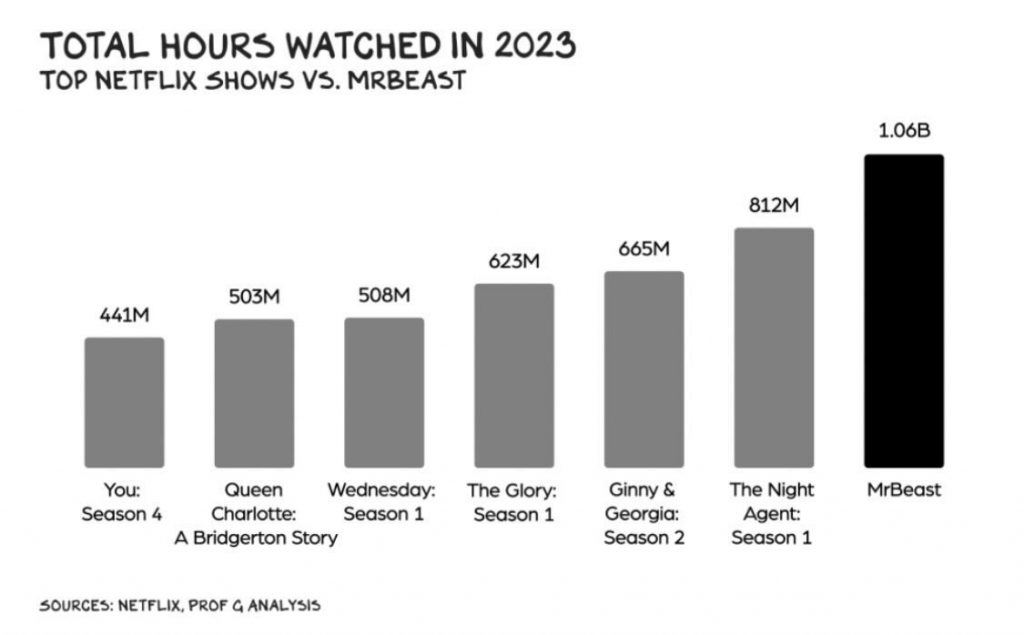

Ever heard of Mr Beast? He was paid out $54 million in YouTube ad revenue in 2023. He has 238 million subscribers, and he is 25 years old. In 2023, Professor Scott Galloway estimates that his videos were watched for a gargantuan 1.06billion hours. This compares to Netflix’s most watched show, “The Night Agent: Season 1”, at just 812m hours (Figure 1).

Figure 1

It’s hard not to disagree with “Prof G” when he argues on his podcast that the future is content made by amateurs and consumed on a phone or console. According to Statista the value of the global video game industry was $350 billion in 2023. Getting precise numbers on YouTube’s total payouts to creators is harder, but estimates are around the $10 billion mark in 2023. By contrast, the global box office for Hollywood came in $34 billion in 2023 with $9 billion of ticket sales in North America. It’s hard not to conclude that cinema is deadest, TV is dead-ish, and long live YouTube and TikTok.

For those spun into a melancholy daze at this new reality, I would highly recommend David Thomson’s “Remotely”. Thomson, like Biskind, is in his 80s, and his knowledge of cinema is unmatched. He has written dozens of books on cinema, but this new tome is a highly personal essay on the TV he watched with his wife Lucy during the pandemic. He has insightful things to say about all of the greats from “I Love Lucy” to “Ozark” to “Succession”. The book is, in some ways, rather indulgent, resisting clear delineation of shows and themes by chapters. But I felt smarter and enriched by the end of it.

Media reviewed:

Remotely: Travels In The Binge of TV by David Thomson

Pandora’s Box: How Guts, Guile and Greed Upended TV by Peter Biskind

The Prof G podcast hosted by Scott Galloway