There’s no perfect way to measure real estate returns. Here are the pros and cons of each metric.

We at Thesis Driven write a lot about innovative real estate models and concepts. But each project’s success or failure ultimately comes down to the same handful of real estate metrics: yield-on-cost (levered and unlevered) and IRR.

Each metric we use to measure real estate returns—projected or actual—has its own advantages and flaws. But too often I see even sophisticated sponsors and investors getting too focused on one metric at the expense of others, creating a skewed perception of the opportunity at hand.

Today’s letter will explore the pros and cons of each real estate return metric. We’ll discuss the interplay between different metrics and how combinations of metrics—such as UYOC, IRR, OER, and equity multiple—can complement each other and paint a fuller picture of a deal.

Metric #1: Unlevered Yield on Cost (UYOC)

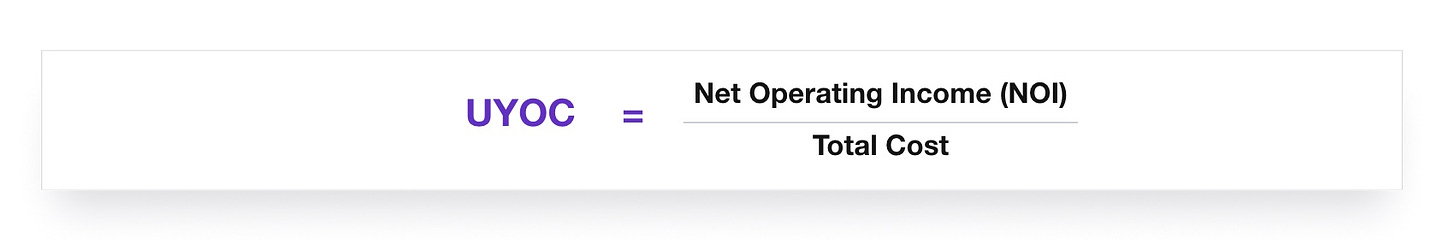

We’ll start with my favorite metric: Unlevered Yield-on-Cost. UYOC is perhaps the simplest metric out there: it’s the Net Operating Income (NOI) of a property divided by the total cost incurred to generate that NOI. For a stabilized, cash-flowing property, “total cost” is simply the purchase price. For a development project, total cost includes the land cost plus any hard and soft costs incurred to develop the asset.

UYOC often gets confused with a similar metric, cap rate. It’s an understandable confusion, as the cap rate equation is quite similar:

“MV” here is the market value of the property. While the cap rate and UYOC equations look similar, “cost” and “market value” are fundamentally different things: cost is what the developer put in to create the cash flow whereas ‘“market value” is what the cash flow is worth.

In the words of ReSeed’s Moses Kagan, “cap rate is what you buy, yield on cost is what you create.” Ideally, a newly-developed property’s market value is higher than the total cost that went into developing it, meaning that—from the developer’s perspective—the property’s cap rate (upon sale) should be lower than its unlevered yield-on-cost.

You often hear related terms thrown around like “cash on cash yield,” which some real estate investors substitute for UYOC. It’s not a particularly accurate substitution, however, as NOI is not cash flow.

Why it’s useful

I love UYOC as a metric as an underwriting metric because it’s very hard to manipulate. All the assumptions that go into it are straightforward and (relatively) easy to interrogate:

- Are you rents correct / in-line with comps?

- Any weird trended rents?

- Are expenses reasonable / in-line with the T-12 (if a stabilized asset)?

- Are development costs reasonable?

While each of these can certainly be juiced to create an unrealistically optimistic picture of reality, they’re not as subjective as some of the other inputs we’ll discuss below.

Evaluating a developer’s track record of delivering UYOC in line with underwriting is also a fairer assessment of his or her capabilities and trustworthiness versus, say, IRR. If a developer underwrote unrealistically high rents but got bailed out by a strong capital markets environment and therefore hit their IRR target, should you really believe the rents on the next deal?

Why it sucks

While UYOC is a solid fundamental metric, it doesn’t paint a realistic picture of how most people—GPs or LPs—make money in real estate. Outside of some family offices and high net-worth individuals, most real estate investors are not buying assets with all equity to clip a coupon every year. The vast majority of investors (a) use debt and (b) anticipate some sort of exit at some point in the future. As a metric, UYOC does not take either into account.

This means that a “good” UYOC varies a lot based on things like the long-term prospects of the property and the rate environment. A “good” yield in a top-tier growth market in a low rate environment might be 3-4%, while a “good” yield in a stagnant market and the current rate environment is probably closer to 7-9%. This difference is because most investors really care about return, not yield, so “good” yields will vary to take into account differences in expected return.

Some developers like to incorporate debt into their yield calculation by using “Levered Yield-on-Cost” as a metric, which basically (a) subtracts the cost of debt service from NOI and (b) only considers equity in the denominator. I don’t love this for a few reasons, mostly because it is highly sensitive to weird—and often risky—debt structures.

Metric #2: Internal Rate of Return (IRR)

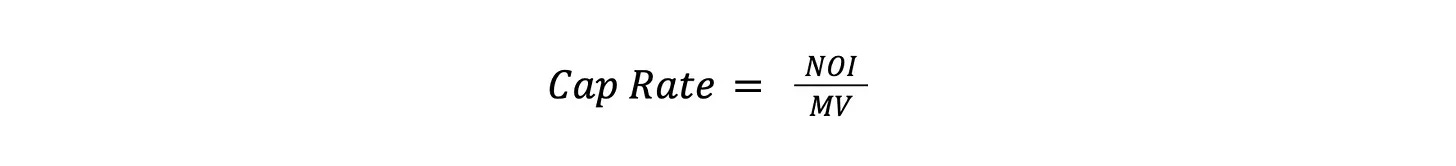

As we discussed, UYOC’s biggest flaw is that it doesn’t really measure what real estate investors are looking for: return. To project total annualized return, we’ll need to make assumptions about a project’s capital stack as well as any eventual exits (or refinancings), and we’ll summarize this as IRR:

It’s often helpful to think about “present value” as the money invested in a real estate project and “future value” as any money returned from the project—distributions during the hold period as well as any refinancing or exit proceeds. Of course, the further out in time distributions happen, the less impact they have on driving strong positive IRR.

Why it’s useful

IRR is the most commonly used real estate metric because it models exactly what most investors want to know: total annualized return over the period of the investment. By focusing on equity investment returns, IRR takes into account the sponsor’s assumptions about not just asset-level performance but also debt financing and eventual exit and return of capital (hopefully). Investors, therefore, are able to get a more complete sense of a sponsor’s business plan and macro assumptions through IRR than they are through UYOC.

In other words, IRR requires that the developer makes a lot of assumptions, including assumptions about things they don’t necessarily have any way of knowing in advance, such as exit cap rate. This is both why IRR is great and why IRR sucks.

Why it sucks

Despite being the most commonly used metric in real estate, IRR is flawed for two main reasons:

(1) It’s very dependent on exit cap rate. This makes forward-looking projections relatively easy to manipulate: if an underwriting isn’t quite hitting the targeted return, it’s trivially simple to project a lower exit cap rate—a higher price—upon future sale of the asset. Given that cap rates move around a lot over time, it’s up to the investor to decide whether the sponsor’s exit cap rate assumptions are reasonable.

This also makes IRR a tough backward-looking metric through which to evaluate a developer’s capabilities. Almost everyone who bought multifamily in the 2010-2018 period came out looking pretty good; even if they badly missed their underwritten rents and suffered expense overruns they were likely bailed out by cap rate compression and a great price upon exit.

(2) It rewards shorter hold periods. The faster money is returned to investors, the higher the IRR. The highest IRRs I’ve ever seen in real estate, for example, came from flipping land. But that’s largely due to the short hold periods of often less than a year. While these kinds of deals can drive astronomical IRRs, they aren’t always good for investors who then must find another place to invest their money.

We’ve previously covered how IRR-driven promote structures create misaligned incentives between long-term oriented investors and real estate GPs, with sponsors effectively encouraged to exit good deals as quickly as possible to maximize their promote.

This flaw can be mitigated by studying IRR in combination with MOIC, which we’ll discuss next.

Metric #3: Multiple on Invested Capital (MOIC)

MOIC is a very simple metric that simply looks at the amount of money returned to investors from a project compared to the amount of money put into that project. This ratio is the “Multiple on Invested Capital,” also sometimes called the “Equity Multiple” of a deal.

A MOIC above 1.0 indicates a profit while a MOIC of less than 1.0 indicates a loss. Like IRR, MOIC is a return metric—that is, it makes assumptions about a project’s exit value, and debt’s impact is taken into account. However, it does not consider the time period of the return; a 2.5x MOIC is a 2.5x MOIC whether it took five years or fifty years to happen.

Why it’s useful

On the surface, MOIC seems far less useful than IRR as a way of measuring return. But it does have a situational role. Consider the land flipping example from earlier: while selling a piece of land three months after it was purchased for a 15% premium may generate a great IRR, it offers an unimpressive MOIC of 1.15x. On the other extreme, holding a great property for fifteen years may generate a modest IRR while offering an exceptional MOIC. While different investors will care about different things based on their goals, IRR and MOIC are best evaluated as a pair.

Why it sucks

MOIC’s flaws are pretty obvious, so we won’t dwell on them too much here. As a forward-looking metric it comes with all of IRR’s assumptive flaws, taking into account a sponsor’s subjective assessment of future cap rates. And as we noted earlier it is agnostic to the time period of a return—it’s simply comparing the amount of money that went out to the amount that’s coming back.

Metric #4: Operating Expense Ratio (OER)

Operating Expense Ratio (OER) is simply the operating expenses required to run an asset divided by an asset’s total revenue.

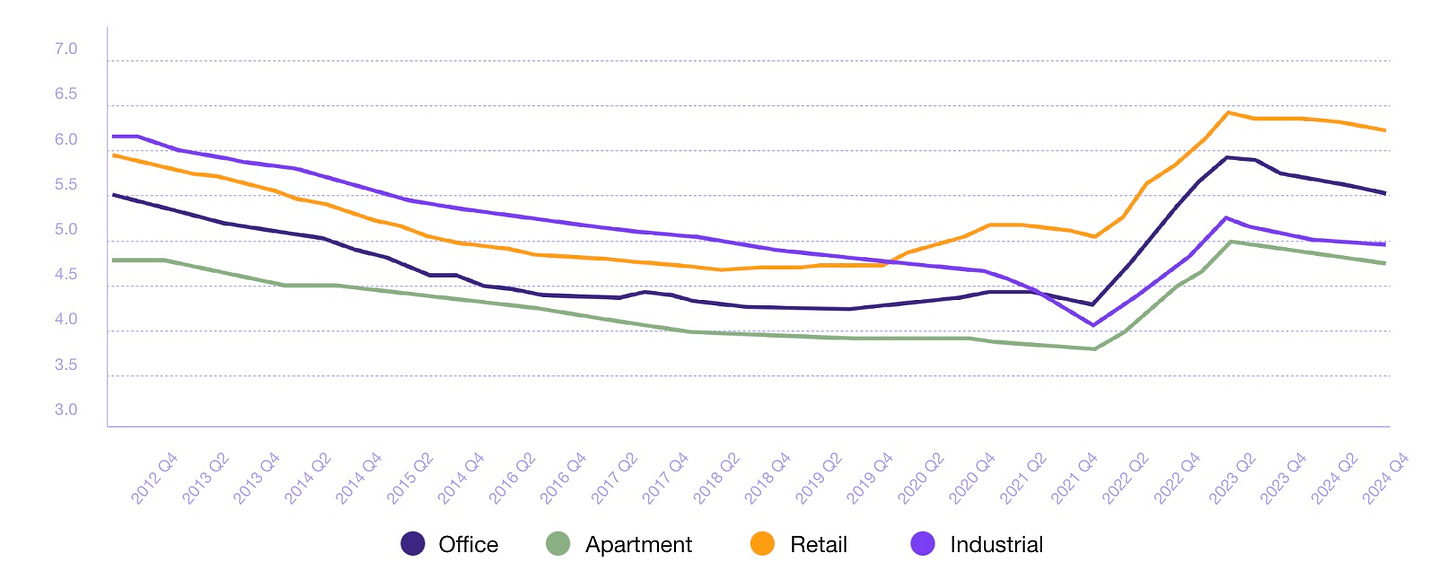

OER is a simple operating metric that says nothing about a project’s returns to investors or yield. And as one might imagine, a “good” OER can vary significantly based on asset type, quality, and location.

Why it’s useful

OER can be a useful way to evaluate the efficiency of an asset. Within a given asset class and quality, comparing two assets’ operating expense ratios can be a quick way to identify potential mismanagement—and opportunity.

When evaluating an underwriting, analyzing a projected OER can also flag overly rosy assumptions. If a sponsor is projecting an OER of 20% in an asset class that typically has operating expense ratios of 30% to 40%, they’re either a really good operator or something is off base.

Why it sucks

Properly evaluating OER requires a lot of knowledge about the asset type, market, and even property-specific conditions—knowledge that many real estate investors don’t have. A “good” OER for a hotel will very different than a good OER for a multifamily building. And a good OER for a Class C multifamily building will be very different than a good OER for a Class A multifamily building. And an OER that looks too fat might be fat for a very specific reason: regulated rents, outdated building systems, union contracts, et cetera.

“Lean” OERs are also not always a good thing—a lower-than-average OER supported by solid rents and modest taxes is very different than a low OER driven by lots of deferred maintenance.

No metric will tell an investor whether a deal is good or bad. At best, metrics—and the relationship between different metrics—will tell an investor which questions to ask. If UYOC looks low yet IRR is high, it’s worth interrogating the hold period and exit cap assumptions. If UYOC is high and OER is low, an investor should question the sponsor’s operating expense and rent assumptions.

Institutional-quality underwriting will also look at each of these metrics in different scenarios, sensitivity testing them across various assumptions of rents, exit cap rates, hold periods, and more. Institutions will also look at “fallback” scenarios if the primary business plan fails. An STR underwriting might show a great IRR and UYOC in the base case, but an institution will want to see what those numbers look like if the asset has to be rented traditionally as well.

There’s no one right way to look at a deal. But by evaluating a deal by multiple metrics across multiple scenarios, an investor can get a solid sense of their risk and return prospects.

This article was originally published in Thesis Driven and is republished here with permission.