It’s not good enough to do “multifamily” or “office” any longer. Real estate sponsors must have a niche.

As the real estate industry enters its third year of elevated interest rates, investors are increasingly looking to niche opportunities to find something—anything—that pencils out. While this has been true for some time, the importance of niche strategies was the notable conclusion from a keynote panel at Blueprint that included managing directors from TRS of Texas and GCM Grosvenor—not exactly firms with a reputation for making fringe bets.

It’s no longer good enough to simply do “multifamily” or “retail.” Real estate sponsors must have a niche.

Niche strategies can be challenging for larger investors who struggle to make a case for how a meaningful amount of capital can be deployed in a reasonable period of time. But growing interest in niches creates opportunity for smaller, entrepreneurial operators who can jump on opportunities early and take advantage of the cap rate compression that comes with growing investor interest.

Today’s letter will tackle the growing role of niche real estate sectors, including:

- Characteristics of a niche;

- Benefits and drawbacks of niche approaches;

- Growing investor interest in niches;

- The path to institutionalization of niche categories.

What’s a Niche, anyway?

Generally, real estate niches are defined by some combination of small market size, uniqueness of the underlying assets, and operational or market specialization. For many institutional investors, “niche” simply means anything beyond the major food groups of real estate—multifamily, office, industrial, retail, and hospitality. This would include data centers despite the $36 billion that went into the category last year, so a rigid definition of a “niche” category is elusive.

But we can look at examples across a few dimensions:

1. Product Specialization

Niche real estate products are often—but not always—physically specialized.

The spectrum of specialization runs from the entire structure being unique to the niche strategy to relatively modest physical modifications. A niche’s level of product specialization is best viewed by asking:

“How much would it cost to convert this asset to something more established? I.e., vanilla multifamily, office, industrial, etc.”

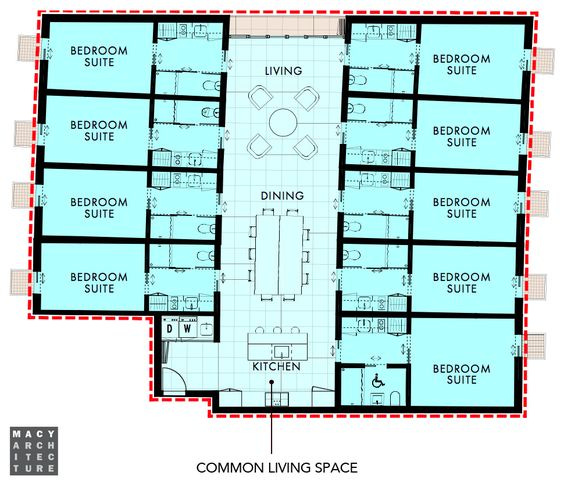

Coliving, for example, was very physically specialized. Many operators built 4, 5, and 6-bedroom apartments that weren’t easily converted back into traditional multifamily layouts.

Source: Macy Architecture.

Short-term rentals, on the other hand, have been comparatively successful given that conversion back to multifamily is trivial. Operating out of “normal” studio, 1- and 2-bedroom layouts means that repurposing STR units—if the need arises—simply involves moving furniture.

This doesn’t mean physical specialization is necessarily a bad thing, but it must come with either (a) yields that are commensurate with the risk or (b) balance sheet guarantees from creditworthy operators. Student housing and specialized retail are examples of each, respectively.

2. Operational Specialization

While physical specialization may be a necessary evil, the best niche strategies focus on operational—rather than product—specialization. This kind of differentiation can be harder to achieve, but it avoids the “fallback scenario” problem outlined above.

Often, operational specialization involves focusing on an underserved target market. Paul Stanton, partner at boutique investment bank PTB and regular Thesis Driven contributor, shares the example of a single-family rental platform with a behavioral health niche that has deployed over $100 million and is currently buying homes to operate at a 9% unlevered yield. A number of niche strategies represent operational innovations on top of single-family and small multifamily assets, from sober living houses to scattered site student housing.

In some cases, operational specialization simply means taking something that was happening informally and formalizing it. Industrial outdoor storage, for instance, is a rapidly growing niche real estate sector. Sure, landowners have been paving lots and renting space out to logistics and construction companies for a long time, but it wasn’t until recent years that real estate investors acknowledged it as a distinct sector.

Operational specialization may also involve some kind of unique regulatory strategy. Tax credit programs—such as historic tax credit development—are one example of a niche real estate development strategy that’s often off-limits to larger investors due to its small scale and operational complexity.

3. Geographic Specialization

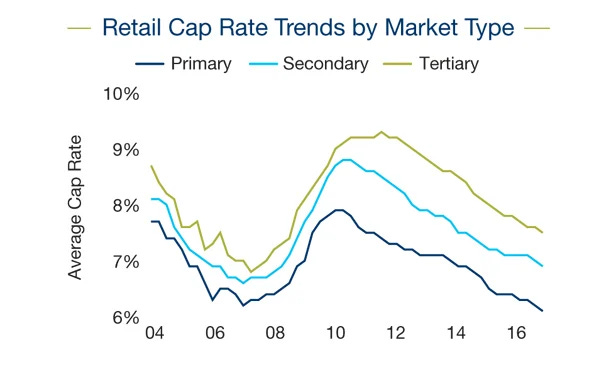

Perhaps the most common “niche” strategy in real estate involves no product or operational innovation whatsoever but merely a commitment to buy in off-the-beaten path markets. Buying established real estate assets in overlooked places has historically been one of the most reliable ways to find higher yields.

Source: GlobeSt

But niche geographic specialization doesn’t have to mean buying in tertiary markets. Even out-of-favor gateway markets can be a barrier for institutional investors and therefore a niche opportunity. Interestingly, the biggest obstacle the home healthcare operator Stanton cited earlier faces isn’t their operational model, but their focus on out-of-favor markets. “Their homes don’t fit neatly into the [institutional investors’] box of buying only in the Sunbelt,” notes Stanton.

Major northeastern and midwestern markets, for instance, haven’t seen nearly as much institutional interest in single-family homes as places like Dallas, Atlanta, and Phoenix. While this is partly due to less compelling macro fundamentals like population growth, it’a also due to homes being less standardized—and therefore tougher to easily underwrite—due to their age.

To Institutionalization and Beyond

While niche investment strategies can clearly provide outsized yields, most real estate investors aren’t investing for yield alone—they’re investing for total returns that likely assume a sale or refi in the not-too-distant future. So while niche strategies may offer eye-popping yields, investors need to take a broader approach and choose niche strategies based on their potential to emerge into a more robust and liquid category.

For most investors, the goal of niche investing is cap rate compression. As a sector matures—with more established operators, investors, asset trades, and seasoning data—perceived risk and cap rates decline, pushing asset prices up. For investors and sponsors holding assets, cap rate compression is the objective.

We covered this process in detail earlier this year when discussed how to build an asset class from scratch. That letter identified five things that emerging asset classes need to grow and thrive:

- A clear definition. What exactly is the asset, and can it be (relatively) standardized?

- Dedicated investors. Are there investors—even small ones—focused on buying and evangelizing the asset?

- Dedicated operators. Are there multiple high-quality operators capable of running the asset?

- Established exit cap rates. Have there been multiple sales of the asset type—ideally to institutional buyers—to get a sense of how the market values it? Are major investment sales brokerages actively covering the asset?

- Seasoning. Are there enough years of operational track record—ideally across business cycles—to establish clear performance metrics?

Each kind of specialization listed in the prior section presents its own challenges to establishing 1-5 above. For example, a highly specialized product might scare off investors who are uncomfortable with the fallback scenarios, while a very niche operating strategy may prevent the emergence of multiple qualified operators needed for a robust market. And tertiary markets may suffer from a thin secondary sales market, making establishing cap rates challenging.

When considering niches, real estate investors evaluate a the sector—and its prospects for institutionalization—just as much as they do the individual asset and operating plan. “Institutional investors worry less about the ‘TAM’ of the niche asset class,” says Stanton. “Instead, the more nuanced question institutions will ask related to market size is ‘Do we believe there will be enough institutional demand in 5-7 years to buy the portfolio of the niche assets we acquire at an attractive cap rate?’”

“For example, buying portfolios of vacation homes, a niche asset class, represents a very large TAM,” continues Stanton. “And many institutional investors showed interest in this niche market from 2021 until mid-2023. But ultimately they could not get comfortable that there would be a line of institutional buyers ready to acquire their portfolios in 5-7 years, primarily because the asset class lacked long-term operating history, and there was no example of a portfolio sale on a cap rate basis.”

The Nichification of Real Estate

Investors don’t want to invest in niches for the sake of investing in niches. But when most deals don’t work, capital will seek out the little opportunities in the market that do pencil. And there’s a lot of capital out there right now looking for a return. “Investors are certainly not interested in niche strategies because they want to be—it’s just the only place to find real alpha,” said Stanton.

Of course, what qualifies as a fringe niche depends on the investor. For some of the largest institutional investors, data centers and life science assets are still niche concepts, while other investors are focused solely on small and emerging niches that institutional investors wouldn’t even consider.

“Family offices are ideal for backing small and new niches,” notes Stanton. “Unlike private equity real estate firms and hedge funds who have strict, defined mandates for what they can and can’t invest in from their institutional investors (pension funds, endowments, etc), family offices have very flexible mandates as the family members can—in theory—invest in whatever they want.”

“That said, this flexibility cuts both ways, as family offices can be interested in niche real estate strategies one day but pivot to investing in crypto or a tech startup the next if that looks more attractive.”

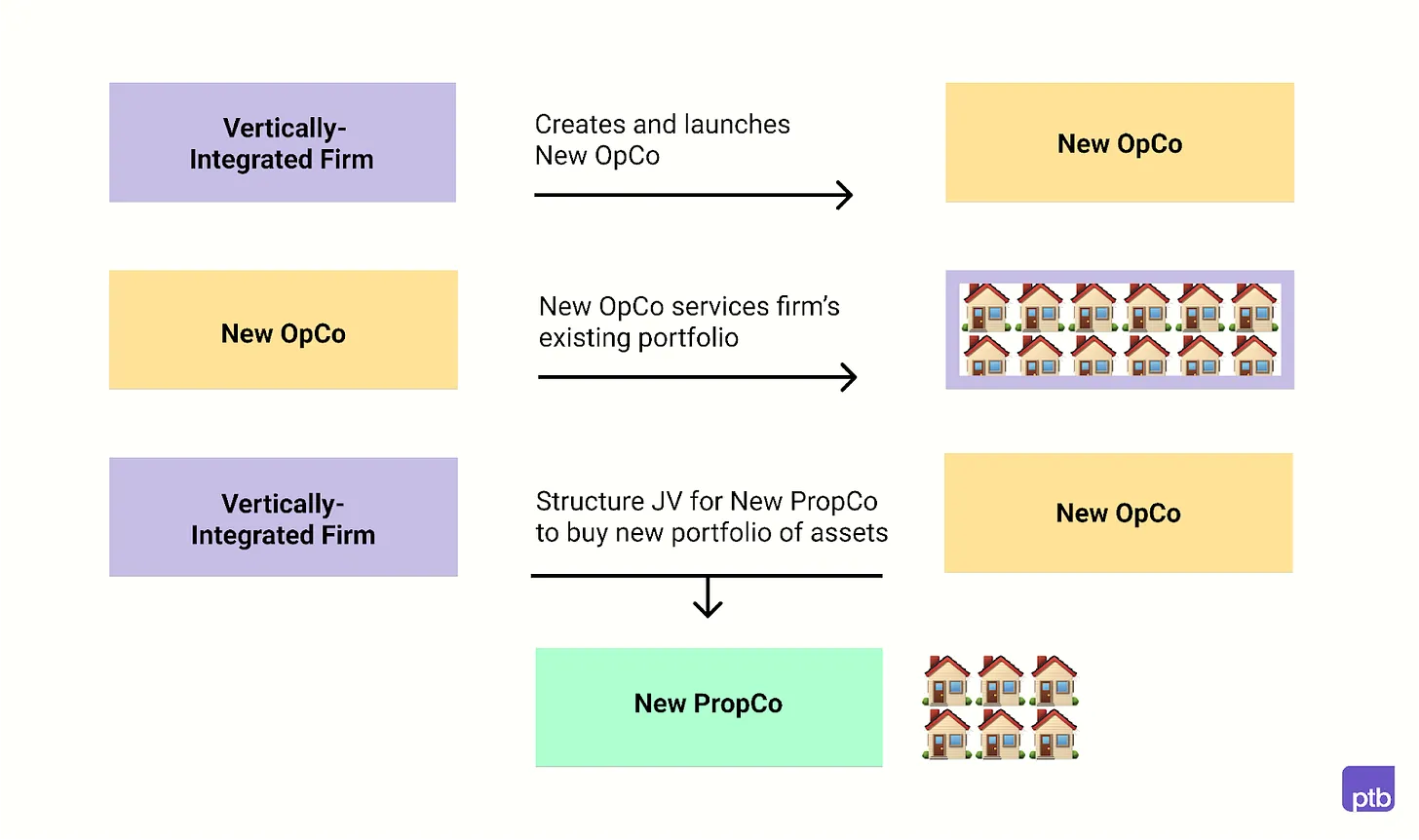

But the past decade has seen the rise of a new type of firm dedicated to investing in niche and novel concepts. “There are a number of new emerging platform investors and GP funds—such as Cloudland and Fireside—that have raised money specifically to invest in niche, operationally complex businesses,” said Stanton. This new generation of firms often adapted investment models from the hospitality industry—such as OpCo-PropCo structures—to get exposure to both the operating company pursuing the niche as well as the underlying assets.

Incubations of new OpCos are another common way for established real estate firms to tackle niche concepts that might be too small or unproven for their normal investment process. In this case, established firms leverage their platforms, portfolios and balance sheets to partner with entrepreneurs to create in-house, purpose-built OpCo-PropCos.

Vornado’s incubation of apartment-hotel operator Placemakr, Capstone’s incubation of Portal Warehousing, and Tishman Speyer’s incubation of managed office operator Studio are all examples of established firms using their balance sheet and portfolio to incubate new, niche real estate operating concepts.

When I wrote about establishing new asset classes this year, I ended with a point I’d like to reiterate here: just because you can doesn’t mean you should:

“Before we wrap up this how-to, I’d like to end with an important reminder: a “new asset class” isn’t always a good thing for investors and operators. In many cases, operators would be better off trying to blend in with an existing product—even if it seems less ambitious and won’t land plum speaking gigs.

“In many cases, a new asset category will be seen as riskier than the parent. Coliving and flex rentals, for instance, both suffered from higher cap rates—implying greater risk—than their parent multifamily sector. (Kasa founder Roman Pedan dove deep into this late last year). In those cases, operators go out of their way to maintain the original multifamily cap rate by building more “conventional-looking” coliving units or limiting the percentage of the building dedicated to flex rentals, for instance.”

While I was at Common, we observed that the ideal time for the embrace of a niche strategy like coliving was when investors were facing enough pressure to get them looking for novel solutions but not so much pressure to send them into a panic. When traditional strategies are working swimmingly (think 2016-2018 and 2021), there’s no need for the brain damage of a niche approach. But the kind of uncertainty that freezes capital markets altogether (think March to July of 2020 or late 2022) is also bad, as no investment committee wants to make a bet on anything.

In other words, there’s a distress sweet spot for building niche real estate strategies. For the moment, at least, we might be in it.

This article was originally published in Thesis Driven and is republished here with permission.