Is the REIT a solution to real estate capital markets woes?

The capital markets are a miracle. Global capital markets are a miracle. But let’s focus on the biggest and best of them all: the US Stock Market.

This whole thing got started when 24 stockbrokers signed an agreement under a buttonwood tree next to what is now 68 Wall Street in 1792. To sign the agreement, they used a quill pen, an instrument made from the central shaft of a large bird’s feather. The Buttonwood Agreement—the formation of the New York Stock Exchange—was signed with an actual bird feather.

The stock market has come a long way since the quill pen and the Buttonwood Agreement. US stock exchanges now trade more than 10 billion shares per day, and the NYSE processes over 1.5 million quotes per second at trading peaks. Three months ago, on June 28, 2024, during the Russell index reconstitution, Nasdaq executed 2,899,191,109 shares (over $95 billion) in 0.878 seconds.

And, of course, real estate also found its way to public markets via public Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs). REITs began public trading in 1960 following the Real Estate Investment Trust Act. As of 2024, they accounted for approximately 3-4% of the U.S. stock market’s total value, with a market capitalization of around $1.25 trillion.

REITs allow real estate holding companies to access the miracle of the US stock market. That means accessing liquidity and accessing capital. It is a path to grow through issuing new shares. It forces disclosure and transparency. It facilitates price discovery. And! There are some tax benefits thrown in for good measure.

Today’s letter will dive into what a REIT actually is, why public markets should be more accommodative to real estate companies, as well as:

- How do you form a REIT, and why might it make sense depending on your strategy?

- The difference between private, non-traded, and public REITs

- The power of using 721 Exchanges or UPREIT transactions

- How public markets don’t accurately reflect the commercial real estate markets

- A view on how small to mid-size real estate firms could access public markets liquidity.

What is a REIT and How to Form One

REITs represent a fascinating intersection of the tangible world of bricks and mortar with the digital realm of highly liquid trading. They allow real estate companies to harness the power of public markets, offering increased liquidity, easier access to capital, and attractive tax benefits.

But what exactly is a REIT, and how does one form one?

At its core, a REIT is a company that owns, operates, or finances income-generating real estate. The journey to becoming a REIT is not simple, but it’s a path worth considering for many real estate companies. To form a REIT, a company must organize as a corporation, trust, or association, be managed by a board of directors or trustees, and have transferable shares. It needs at least 100 shareholders and must pay out at least 90% of its taxable income as dividends. Furthermore, at least 75% of its assets must be invested in real estate or cash; the same percentage of its gross income should come from real estate-related sources.

Why go through all this trouble? For many real estate firms, the benefits are compelling. Access to public market liquidity can be a game-changer, allowing for easier capital raising for expansion. The tax benefits are significant, too—REITs don’t pay corporate income tax on distributed earnings. Every tool available to private real estate investors, from accelerated depreciation to 1031 exchanges to Opportunity Zones, is available to REITs; it simply occurs at the corporate level before distributions are paid out. Plus, the increased transparency of being a public entity can potentially lead to improved valuations. Of course, that comes with increased operating costs. More on that later.

Most crucially, a REIT structure offers permanent capital. Rising rates and frozen transaction volumes caught many real estate investors in defined-duration structures like syndications and funds offside. Forced sales or sub-optimal recapitalizations driven by operating agreements showed many sponsors the benefit of having longer-duration capital to pursue their strategies.

S2 Capital, a prolific multifamily syndicator, successfully rolled 26 separate JVs into a private REIT targeting $100 million in proceeds from new investors. According to PERE,

“S2C Real Estate Income Trust will be the largest multifamily-focused private REIT by number of operating units. The second-largest non-traded REIT focused on the sector, Cottonwood Communities Advisors’ Cottonwood Communities, had 7,761 operating units as of December 31, according to the vehicle’s most recent prospectus.

“Although many of private real estate’s largest managers have focused on raising diversified non-traded REITs – such as Blackstone’s Blackstone Real Estate Income Trust and Starwood Capital Group’s Starwood Real Estate Income Trust – the number of sector-specific private REITs has been on the rise.“

Different Flavors of REITs

Not all REITs are created equal. Public REITs on stock exchanges offer the highest liquidity and transparency. They can be bought and sold like any other public stock, making them accessible to a wide range of investors.

On the other hand, private REITs, not listed on public exchanges, are typically only available to institutional or accredited investors. These private REITs offer the benefits of permanent capital and the tax benefits that come with REIT status, but without a market for the shares they are closer to evergreen private equity vehicles. They offer less liquidity but may provide access to more diverse real estate portfolios. Sitting between these two are non-traded REITs, registered with the SEC but not trading on public exchanges. They offer a middle ground in terms of liquidity and accessibility.

We have performed a deep-dive analysis of Blackstone’s BREIT, which found that permanent capital without price discovery can cause the same problems as defined-life private structures. BREIT is a non-traded REIT, which means that the sponsor is willing to make a market in the shares at the reported Net Asset Value (NAV) subject to certain limitations. The challenges and incentive misalignments that can arise when a manager has to set Net Asset Values in an opaque pricing environment create a very crowded theater with a very tiny door. There is the added misalignment of charging fees on a “NAV” at which the underlying investor may or may not be able to transact.

Some enterprising firms, like Groma, are using Regulation A to begin their lives as private REITs but with the ability to raise capital from unaccredited investors. Reg A is an exemption from registration for public offerings, allowing smaller companies to offer and sell securities to the public but with more limited disclosure requirements than a traditional IPO. Groma focuses on smaller, urban multifamily properties, a real estate type without a comparable public market.

Groma is also promoting another key benefit of the REIT structure: the 721 exchange, or UPREIT. 721 exchanges and UPREITs (Umbrella Partnership Real Estate Investment Trusts) offer strategic alternatives to the well-known 1031 exchange. While a 1031 exchange allows investors to defer capital gains tax by swapping one investment property for another of like-kind, 721 exchanges and UPREITs provide different mechanisms for tax deferral and portfolio diversification.

A 721 exchange enables property owners to contribute real estate to a partnership in exchange for partnership interests, deferring capital gains tax. This differs from a 1031 exchange in that the investor receives partnership interests rather than direct ownership of a replacement property.

The UPREIT structure expands on this concept. In a UPREIT, property owners contribute real estate to an Operating Partnership (OP) associated with a REIT, receiving OP units in return. The ability to use OP units as a currency for acquisitions creates a compelling edge in competitive markets.

Bonaventure, a multifamily investment firm focused on the mid-Atlantic, has used 721 exchanges to grow the portfolio of their Bonaventure Multifamily Income Trust (BMIT), to over $1 billion. In the past 18 months, Bonaventure added at least $96.5 million of assets to the portfolio through structured 721 exchange transactions. Dwight Dunton, CEO and Founder of Bonaventure, said, “Our ability to offer flexible deal structures and tax-efficient solutions, such as 721 exchanges and 1031 exchanges, has been a key differentiator for BMIT in this market.”

While these structures help sponsors better acquire and capitalize deals, they do little to offer ready liquidity. They do, however, bring both the sponsor and the investors one step closer to public markets.

A Market Starved for Assets

From the investor’s standpoint, listed REITs allow public market investors to access physical real estate quickly and efficiently. The Buttonwood crew could never have imagined what we built on their agreement. Listed REITs take an investment process that includes appraisers, paper contracts, and endless direct negotiations, and it streamlines it into a couple of clicks.

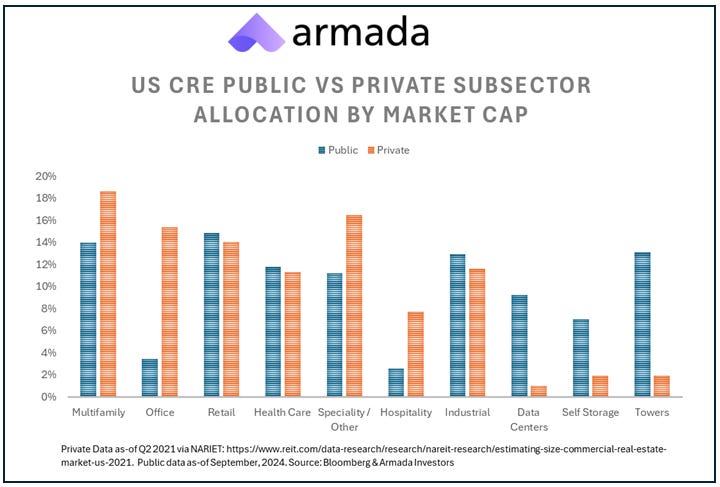

It is amazing, but it is not perfect, not yet. For one thing, listed REITs comprise a small subset of the US commercial real estate market. Right now, they comprise about 6% of the CRE market, meaning we see all sorts of sub-sector and geographic weighting distortions. For example, while the public markets reflect a 10-15% market cap weight for multi-family, apartments actually represent close to 20% of the total US CRE marker. The opposite is true of cell towers, where the market capitalization of tower REITs represents nearly 14% of public markets; they are less than 5% of the total US CRE market.

The thing is, the “RE” in REIT doesn’t necessarily stand for Real Estate as it might commonly be understood. A REIT is a tax election, and a brilliant way to access public markets. So we see cell towers, timberland and data centers getting lumped in with more traditional real estate. Why? Well, for capital intensive businesses like Data Centers or Timber, it can be more advantageous to be valued on real estate multiples than on operating company metrics.

Data centers, for example, are highly capital-intensive and require near-constant investment to stay competitive. Depreciation on those investments would punitively hit Earnings per Share and Price-to-Earnings ratios. The REIT election shifts the analytical narrative to cash flow-based metrics like Funds From Operations.

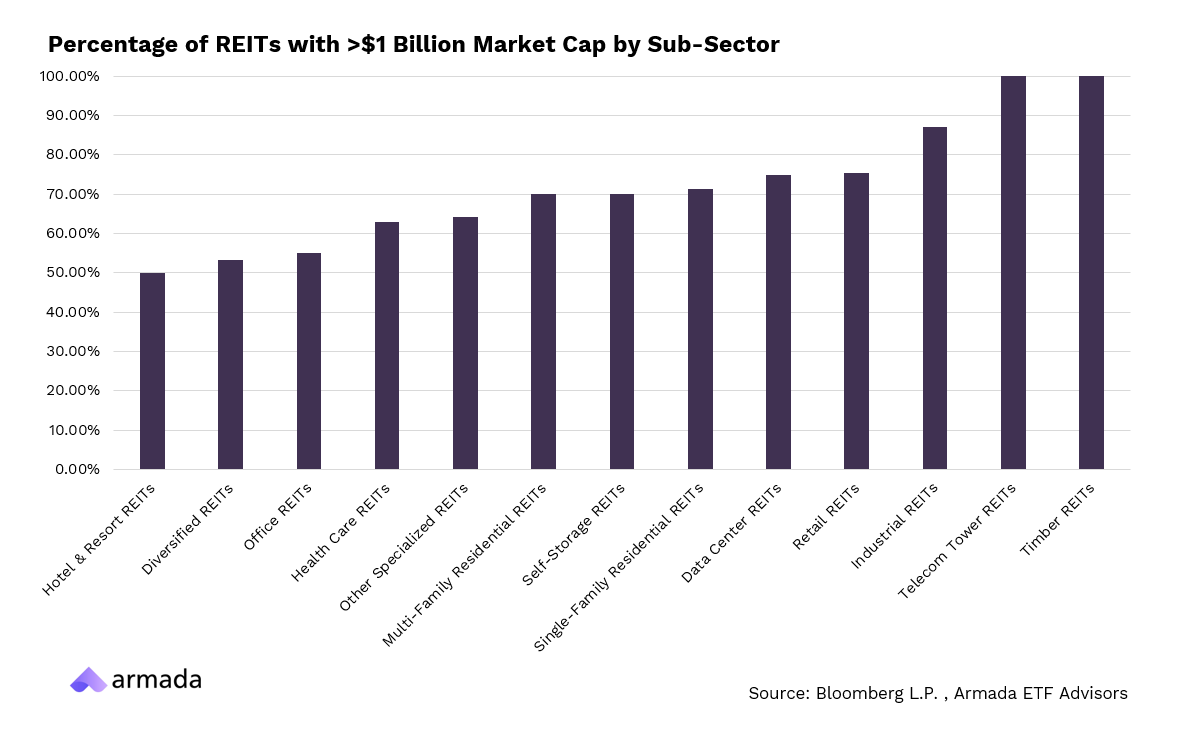

That is not necessarily a bad thing, but it is something to note and be cognizant of. It leaves a hole in the market for more targeted “pure” real estate. Further, the REIT sectors tend to be lumpy in terms of size, with a few giants in each sub-sector making up a significant portion of that sub-sector. For example, in industrial, Prologis (PLD) is more than 6 times larger than second largest, Lineage (LINE).

If an investor wants to express a view, say specifically on industrial in the Southeast, or in manufacturing facilities, the current listed REIT landscape makes that kind of exposure challenging to create. Smaller real estate portfolios finding their way to public markets would make the sector more robust and more useful from a traditional portfolio management standpoint.

This year has seen a handful of REIT IPOs, an encouraging sign. Cold storage giant Lineage IPO’d with a +$20 billion valuation, putting it in the top ~20 of U.S. listed REITs. So far it is 2024’s largest IPO. Just this week FrontView, a REIT focused on high-traffic retail assets, announced plans for an IPO that would value it at over $500 million. Both were private REITs before making the jump to public markets.

Of course, being public is no picnic. The compliance and reporting costs are staggering, and with a growing passive share of investor capital, trading a premium to NAV requires an outsized investor relations effort to tell your story and have the market actually care.

The journey begins with the costly IPO process, where millions can be spent on underwriting, legal, and accounting fees. Once public, the hurdles multiply. Ongoing compliance with SEC regulations and Sarbanes-Oxley standards becomes a constant drain on resources. Smaller REITs often find themselves caught in a visibility trap, struggling with limited analyst coverage and lower trading volumes, which can lead to undervaluation and higher capital costs.

The public spotlight brings its own set of pressures. Management teams find themselves pulled away from core operations, spending valuable time on investor relations and addressing short-term market concerns. This can create a strategic tug-of-war between long-term real estate goals and quarterly earnings expectations.

Making Way for Smaller REITs

There has been a lot of chatter about private market liquidity being frozen, but the public markets have no such liquidity issue. The stock market is as liquid as it ever has been. Accessing the public markets makes sense for real estate firms with no clear path to liquidity on the private side.

The REIT structure has generally been available for massive real estate firms, just as mutual fund and exchange-traded fund issuance once carried a tremendous cost barrier. In the fund space, those costs have dropped dramatically, in large part due to the prevalence of “white label issuers”.

White-label ETF issuers revolutionized the ETF industry by significantly lowering barriers to entry. This model allows smaller asset managers to launch ETFs without the substantial infrastructure and regulatory burdens typically associated with fund creation and management. White Label providers handle the complex aspects of fund operations, including regulatory compliance, administration, and distribution, all at the same economies of scale as their larger competitors. This enables clients to focus on their investment strategies.

This approach dramatically reduced costs and streamlined the process of bringing ETFs to market. It shortened time-to-market, decreased initial capital requirements, and allowed for economies of scale in operations and compliance. The result was a proliferation of niche and innovative ETF offerings, enriching the investment landscape.

A similar model could potentially transform the REIT industry. A “White Label REIT” structure could offer smaller real estate companies a way to access public markets without the full burden of going public independently. This hypothetical structure might handle SEC compliance, investor relations, and other regulatory requirements, allowing smaller real estate firms to focus on property management and acquisition strategies.

Such a model could potentially lower costs, improve operational efficiency, and provide economies of scale for smaller REITs. It might enable more diverse real estate portfolios to reach public markets, offering investors broader choices. However, challenges would include maintaining individual REIT identities, navigating complex real estate regulations, and ensuring proper alignment of interests between the White Label provider and the underlying real estate companies, and introducing those real estate firms to the capital market players that will ultimately determine valuation.

By allowing private real estate firms access to liquidity and bringing more real estate investment options to the public markets, we can bridge the worlds of public and private real estate. This would allow real estate firms of all sizes to participate in the miracle of the market and help them access liquidity, better tax treatments, and a chance for higher valuations.

This article was originally published in Thesis Driven and is republished here with permission.