Most newcomers to Bitcoin understand its attempt to be digital gold―a store of value native to the internet. But which is better?

On the one hand, you have a time-tested precious metal with low inflation and steady value appreciation. On the other, an extremely volatile, newly-invented internet coin that acts more like a risk asset than a store of value. For millennia, gold has been a universal store of value, but younger generations like mine are now increasingly turning to Bitcoin. This shift feels like more of a movement than an investment trend, and I’d like to explore why.

Throughout history, I believe money has always been what was hardest to produce. Rai stones in Micronesia were used as currency since it was incredibly difficult to quarry and transport, often exchanging ownership without moving the stone itself. Glass beads and wampum (beads made from shells) were used as currency in Native America, Africa and Asia as they were difficult to produce and obtain, often involving extensive trade routes. Feathers from rare birds that were intricately woven into long coils were used as currency in the Solomon Islands. Salt was used as a medium of exchange in Ancient Rome, often paying soldiers in salt, giving rise to the word “salary”.

Each of these examples eventually gave way to gold. Rai stones were impractical to move given their size and weight. Wampum’s production over time became easier, leading to inflation and a loss of scarcity. The fragility of feathers contributed to their demise. Salt became widely available through new mining methods, ramping up supply and debasing its value. In each case, money lost its value as a currency for one of three reasons: it was too difficult to transport, it lacked durability, or it couldn’t maintain its scarcity.

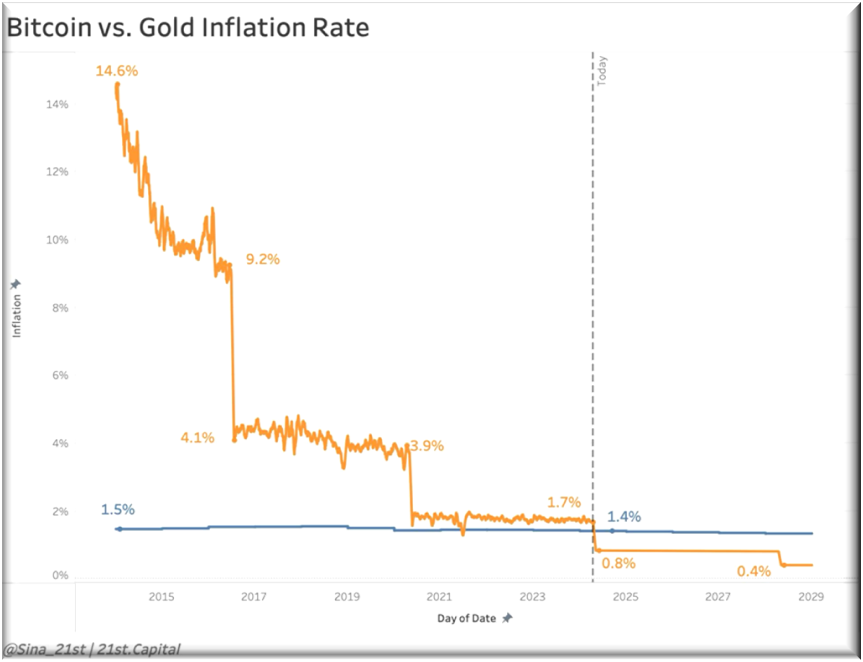

Enter gold, an indestructible, portable, and costly-to-extract metal that has long held its place as the world’s most accepted and oldest store of value. It has earned the trust of older generations and conservative investors who value stability. With an annual inflation rate of around 1.4%, the amount of new gold entering the market each year is small enough to preserve its scarcity and, by extension, its value.

So, how does Bitcoin compete with gold?

Bitcoin operates in a completely different realm, one shaped by the digital age. In today’s increasingly connected world, where data moves seamlessly across the globe, transferring value should be just as simple. That’s where Bitcoin comes in. As both a currency and a payment network, it allows anyone to send value instantly to anyone, anywhere in the world. Its digital nature makes it far more portable than gold. What sets Bitcoin apart is its foundation on blockchain technology – an unchangeable, decentralised protocol that guarantees digital ownership without relying on any central authority.

Gold, despite its stability, is subject to centralisation. It can be confiscated, and governments and central banks hold significant reserves, allowing them to manipulate its market value. Bitcoin, on the other hand, is decentralised, resistant to censorship, seizure, or government interference. Its decentralised nature is a key reason why I believe younger generations―who tend to be distrustful of centralised institutions―are drawn to Bitcoin. It offers financial sovereignty, allowing individuals to truly own and control their wealth without relying on third parties.

But what about its scarcity?

Without getting too technical, Bitcoin’s supply is controlled by its code. Every four years, the amount of new bitcoin that enters circulation is halved, an event known as the “halving”. This year, Bitcoin’s inflation rate dropped from 1.7% to 0.8%, officially making it scarcer than gold for the first time in history. Since Bitcoin is a fixed supply asset, only 21 million bitcoins will ever be produced, with its inflation rate continuing to halve every four years until the last few remaining bitcoins are mined in 2140.

Unlike every other asset you can think of, including gold, Bitcoin is the only asset that’s inelastic to price. No matter how high its price goes, it’s impossible to speed up its production.

While gold’s industrial uses, especially in jewellery and electronics, add utility and offer a very real sense of value, the vast majority of its worth comes from its monetary properties, not its utility. Bitcoin, by contrast, has no tangible use. Its value is purely tied to its scarcity, decentralisation, and role as a store of wealth, arguably making it less vulnerable to external factors that influence gold’s market value.

For older generations, gold remains a trusted and stable store of value. However, Bitcoin’s appeal lies in its monetary innovation, financial sovereignty, and potential for significant price appreciation. With no investor ever losing money when held for four years, Bitcoin offers younger generations a modern and transformative approach to wealth preservation that might just trump gold.