Just some mysteries from the world of borrowing, risk, and price signals.

And we’re back, after a marathon Jewish holiday season.

- lossmaking smallcaps increase (and the crowd goes wild)

- when rates go up, SMBs borrow more?

- when rates go up, borrowers pay less(?) interest

- it’s never been a less-risky time to lend

- . . . which is why all the lending goes to lenders

Six charts that aren’t what anyone would have expected (and are somewhat hard to figure).

Lossmaking small caps go up (and the crowd goes wild)

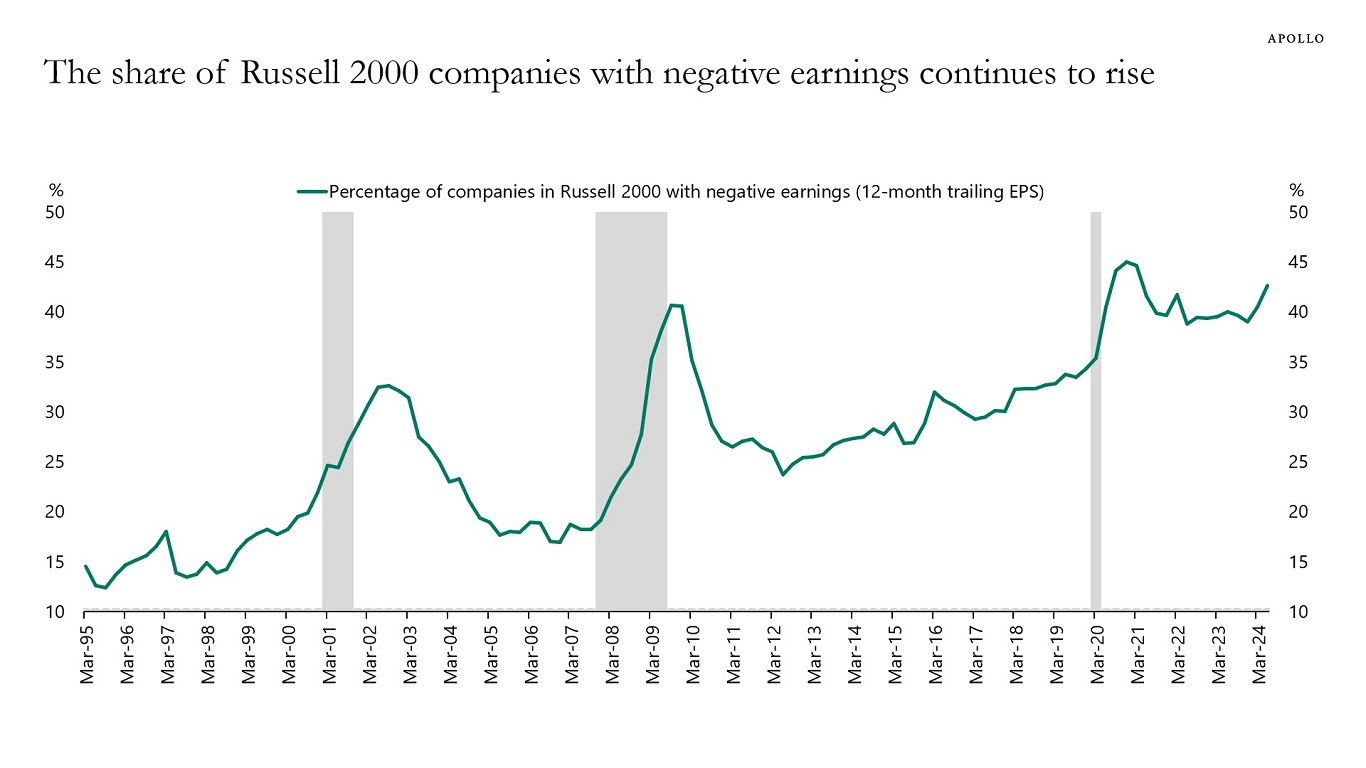

The share of small caps with negative earnings continues to climb:

Loss-making small caps have become increasingly prevalent, essentially on-trend since the GFC (although even more so, lately).

At some point this trend has to roll over, right? I don’t know at what point that is, but they can’t all be lossmakers.

Plus, you know the old adage, that “Private Equity is just small caps with leverage”? If this is what small caps are doing without leverage, then it can’t be pretty with leverage.

Gimme all the junk

Or maybe it can.

Leverage? We love leverage.

Sub-investment grade? Even better:

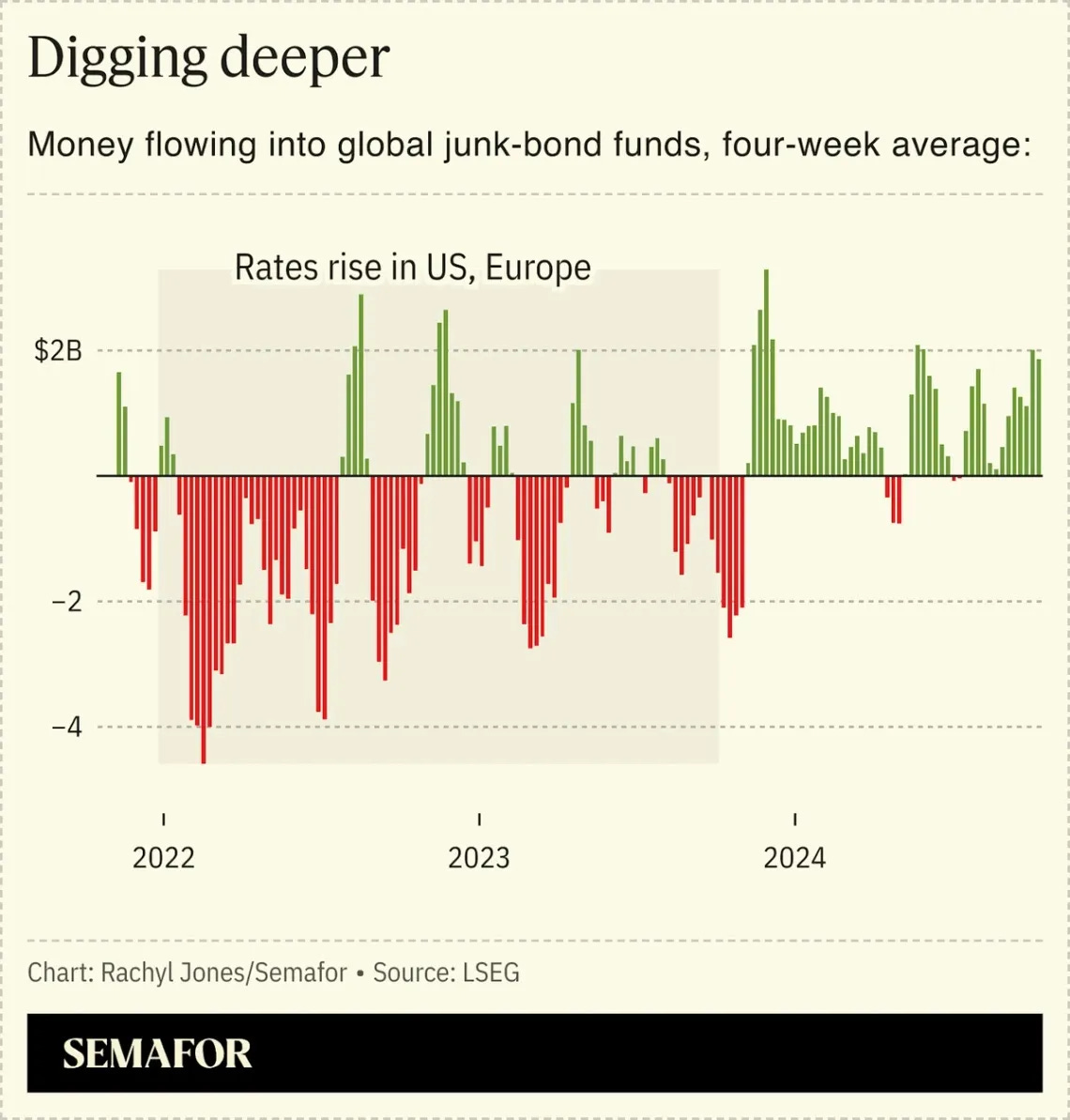

Inflows to “junk” rated debt took off like a rocketship.

The share of loss-making small caps may continue to grow, but that hasn’t stopped lenders from throwing more money at riskier companies.

Presumably, investors thought junk yields were attractive when everyone expected more cuts on the horizon. Query what they think now.

Junk at any price!

Demand for junk was so high that investors were willing to pay top dollar. The toppest dollar, you might even say.

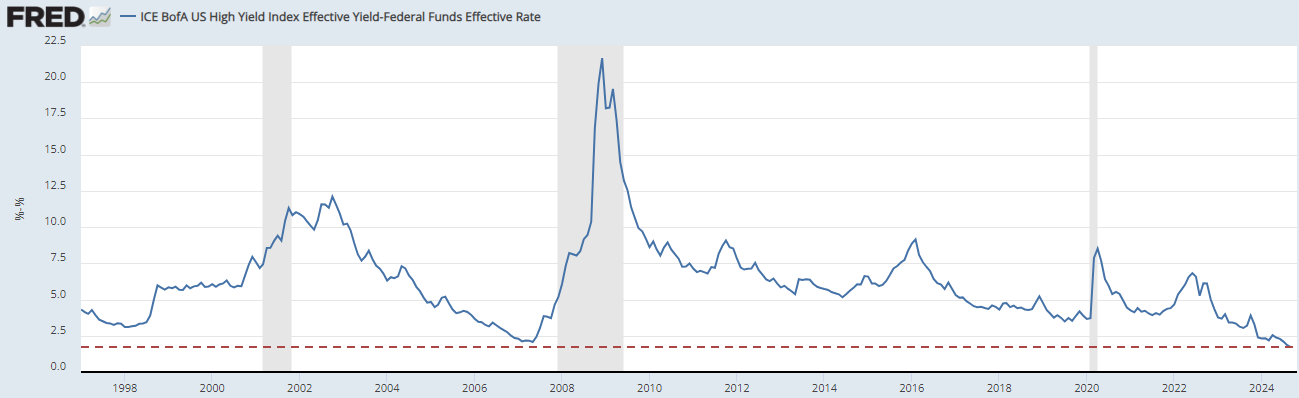

The riskiest stuff is paying only slightly more than the “risk free” stuff:

The difference between high yield “junk” and the Fed Funds “risk free” rate is now smaller than it was in 2007.

As I said, the toppest dollar.

Just to recap:

- the percentage of loss-makers amongst the small caps goes up . . .

- lending to sub-investment grade companies (which is a decent way to describe a lot of loss-making small caps) goes through the roof . . .

- investors are taking this risk, while receiving the least reward than what they’ve received in forever . . .

- and all this is happening in a ‘higher for longer’ climate, where PE-backed companies can’t buy an exit.

. . . and, yet, all of this makes sense, somehow, and the world keeps turning.

When rates go up, small businesses borrow . . . more?

Here’s another mystery of rates and commercial life, involving small businesses (which aren’t necessarily smally caps, to be clear).

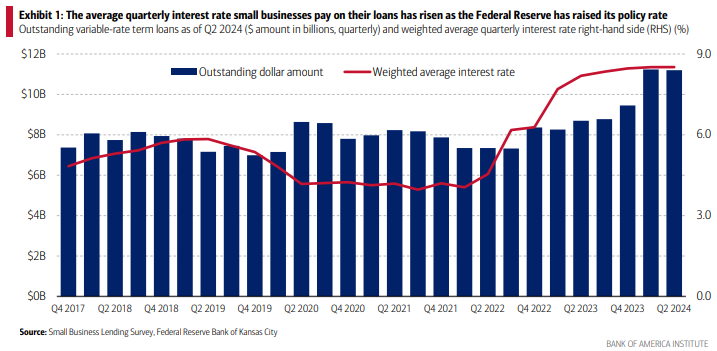

This too is unexpected.

Rates went up and small businesses borrowed . . . more?

Total loan balances increased into the peak of borrowing costs.

Generally, it’s supposed to work the other way.

When borrowing costs go up, it should make borrowing go down (unless you’re Uncle Sam, in which case, you dgaf).

That SMBs have borrowed more at higher rates is even more perplexing given how fine everything has been and appears to be. This should be a harbinger of stress, but if so, where is it?

Maybe without readily available equity, companies are raising debt instead? Or maybe everything is just strange, but also fine.

When rates go up, interest payments . . . go down?

And finally, another little unexpected outcome of the new normal.

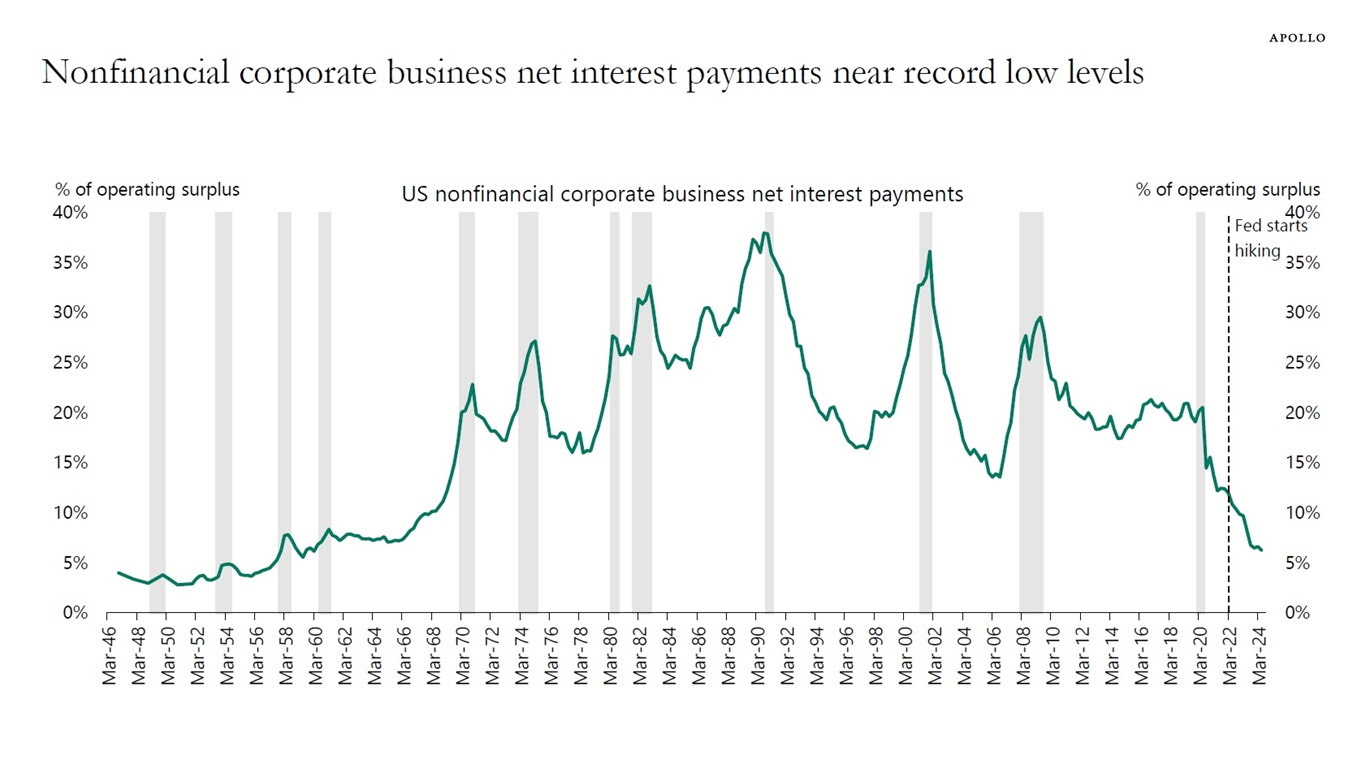

Corporate interest payments are trending towards historical lows!

Net interest payments for corporates is now at 1960s levels.

That’s again, precisely what everyone predicted: when rates go up, borrowing costs go down (obviously).

“Well, it’s just flight to quality,” which ok, sure. The biggest and best companies are hoovering up the credit that’s out there (until recently, at least), and they don’t have to pay much for it.

Plus, “We operate in a “capital light” economy,” OK that too.

Just so much lending

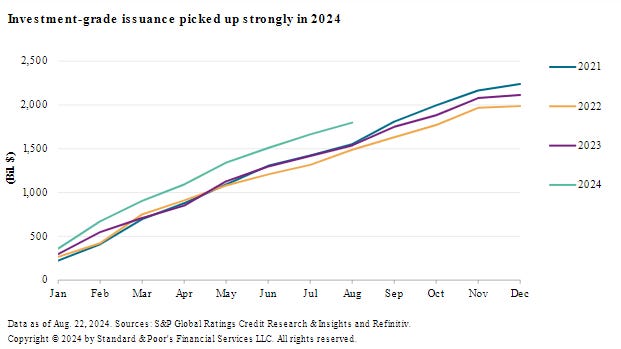

But there’s just so much lending:

Investment grade issuance is gangbusters this year too.

Money has piled into credit, both investment grade and junk, presumably in anticipation of rates coming down.

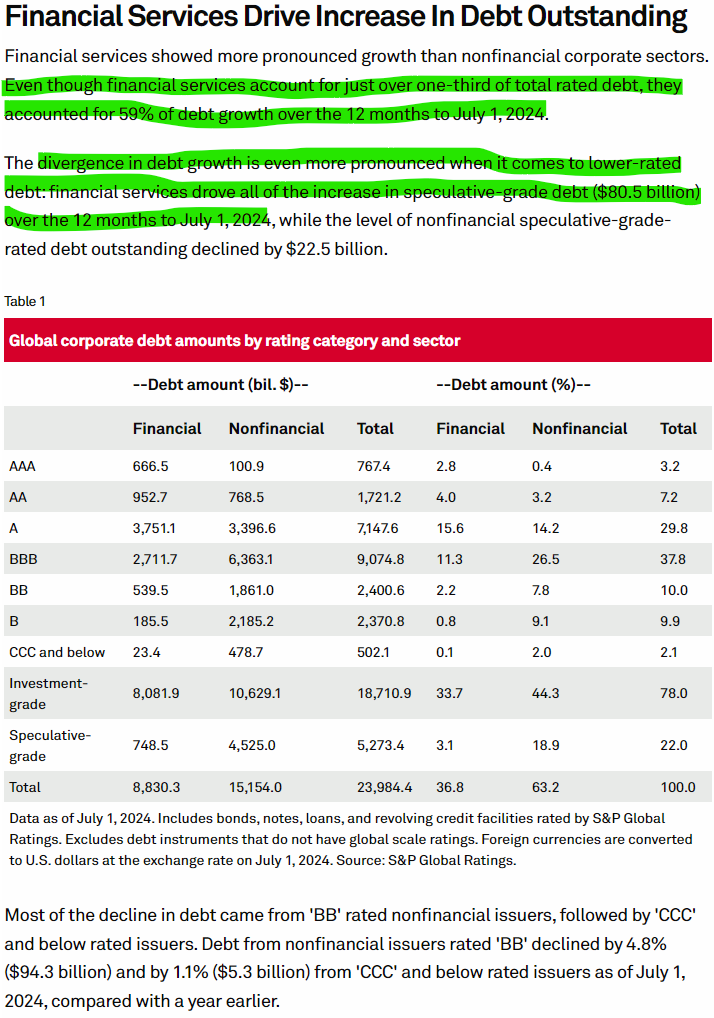

In fact, if you want to put a finer point on it, money has piled into financial institutions specifically—not just generic corporates—presumably already levered financial institutions, so that they can do more leveragy things with it.

Private Credit by itself raised $25B in investment grade notes. But it’s not just them, it’s all the financial services:

As per S&P, financial service firms account for 60% of the debt growth over the last 12 months, including “[100%] of in the increase in speculative-grade debt.”

To repeat, 100% of the increase in junk-rated debt has gone to financial service firms. And it’s probably fine.

Look, with the benefit of hindsight this all makes sense (sort of).

In general, higher rates have reduced the appetite for buying riskier companies, and shifted interest towards lending instead. This is the Howard Marks “sea change.” All that lending has driven the price of debt down, which brings interest payments down, especially recently when investors thought jumbo rate cuts were right around the corner.

And the “get it while it’s hot” moment saved bonus season for a lot of bankers, but still, “incredibly low borrowing costs” is just not what anyone would have predicted.

That ‘capital-starved’ companies are still kicking it, but perhaps slightly less successfully than before, is maybe higher rates catching up to them, or the other shoe still falling, or just something else? idk. But they sure are borrowing a bunch, just as things start looking a little dicey.

There are reasons for all of these, I’m sure, but it’s still a very strange and unexpected monetary “tightening.”

This article was originally published in Random Walk and is republished here with permission.