He’s a great economist, but he also changed how we talk about the subject.

Don’t worry, Paul Krugman is still alive. But he’s retiring as a New York Times columnist, after almost 25 years. He will be greatly missed. (He’s moving to Substack, though, so hopefully he’ll do a lot more blogging!)

When I was in my second year of graduate school, a friend of mine told me that I should start an economics blog, and that I could be the next Paul Krugman. I told her that I was definitely thinking about starting a blog, but there was no possible way I could follow in Krugman’s footsteps. That is still true. In fact, I’m not sure anyone can.

But by a total coincidence, just two years later, Krugman was personally responsible for launching my writing career. When I first started blogging as an angry upstart grad student, Krugman found me through Brad DeLong and Mark Thoma, and started linking to me with a frequency that, frankly, I probably didn’t deserve. I think the first post of mine that he linked to was called “What I Learned in Econ Grad School”, back in April of 2011. I remember being pretty amazed to see my name in the New York Times. Then it became a regular occurrence, and pretty soon I had a following of my own. Looking back, I think there’s a good chance that if Krugman hadn’t discovered me, I wouldn’t be writing this Substack right now.

I say this not just out of personal gratitude, but because it illustrates one way Paul Krugman helped redefine economics writing. Elevating and engaging with nobodies like myself has always been part of his M.O. Krugman’s conversations are a meritocracy of ideas — if you’ve said something he thinks is interesting, he’ll engage with it in the same way whether you’re a legendary academic or a no-name grad student. It’s the ideas that are important to Krugman, not the credentials or the accomplishments of the person who said them.

This is especially important because economics is a profession where hierarchy, credentials, and position are absolutely central. Within the cloistered, closed-off world of the profession, top figures are treated essentially as gods. You can write a paper finding fault with Daron Acemoglu’s research, or Raj Chetty’s, but if you’re a no-name prof from a third-ranked school, or a grad student, your criticisms are generally going to be politely ignored — or at least given a lot less weight than the papers of the superstar you’re challenging. And if, as a low-ranked professor or grad student, you loudly proclaim that Acemoglu or Chetty is wrong, the general response will essentially be “Who are you to talk?”. The pervasive, ever-present power of this internal hierarchy is something you really have to have existed inside the econ profession in order to understand.

Krugman was perfectly positioned to bust this cosseted, hierarchical world wide open. As a top academic with impeccable research credentials — including the Nobel prize in 2008 — he had the authority within the profession to include and elevate outside voices and take their ideas seriously. And he had the authority to question existing academic dogmas, and even to air out the profession’s dirty laundry in public. This is what he did in what consider his most important opinion piece ever, entitled “How Did Economists Get It So Wrong”, which Krugman wrote in September 2009 a year after the financial crisis began. Here are a few excerpts from that excellent piece:

“It’s hard to believe now, but not long ago economists were congratulating themselves over the success of their field…Olivier Blanchard of M.I.T….declared that ‘the state of macro is good.’…[T]he ‘central problem of depression-prevention has been solved,’ declared Robert Lucas of the University of Chicago…

“Last year, everything came apart.

“Few economists saw our current crisis coming, but this predictive failure was the least of the field’s problems. More important was the profession’s blindness to the very possibility of catastrophic failures in a market economy. During the golden years, financial economists came to believe that markets were inherently stable — indeed, that stocks and other assets were always priced just right. There was nothing in the prevailing models suggesting the possibility of the kind of collapse that happened last year. Meanwhile, macroeconomists were divided in their views…Neither side was prepared to cope with an economy that went off the rails despite the Fed’s best efforts.

“And in the wake of the crisis, the fault lines in the economics profession have yawned wider than ever. Lucas says the Obama administration’s stimulus plans are ‘schlock economics,’ and his Chicago colleague John Cochrane says they’re based on discredited ‘fairy tales.’…

“As I see it, the economics profession went astray because economists, as a group, mistook beauty, clad in impressive-looking mathematics, for truth…[A]s memories of the Depression faded, economists fell back in love with the old, idealized vision of an economy in which rational individuals interact in perfect markets, this time gussied up with fancy equations…[T]he central cause of the profession’s failure was the desire for an all-encompassing, intellectually elegant approach that also gave economists a chance to show off their mathematical prowess.

“Unfortunately, this romanticized and sanitized vision of the economy led most economists to ignore all the things that can go wrong. They turned a blind eye to the limitations of human rationality that often lead to bubbles and busts; to the problems of institutions that run amok; to the imperfections of markets — especially financial markets — that can cause the economy’s operating system to undergo sudden, unpredictable crashes; and to the dangers created when regulators don’t believe in regulation.”

This kind of language has become pretty standard now, but in 2009 it was revolutionary — even more so within the economics profession than outside it. It’s the kind of thing you might expect some no-name blogger to say, but to see it uttered by one of the profession’s leading luminaries — on the biggest media stage in existence — was stunning. Some economists hated Krugman for writing this, but most acknowledged that what he said was true, and that things had to change. And he opened the door for a number of other top macroeconomists, like Paul Romer, to vent their own frustrations with their field.

Developments in academic macroeconomics since then — the return of fiscal Keynesianism, the rise of empiricism, the consideration of behavioral ideas — are obviously partly a response to external events, but I think they probably owe something to Krugman’s articles in the New York Times.

Outside academia, Krugman’s 2009 broadside kicked off a golden age of economics blogging. The so-called Macro Wars (a name I think I might have invented, or at least popularized?) were actually a free-ranging discussion about monetary policy, fiscal policy, and the sources of recessions. Besides Krugman — who was often either the instigator or the adjudicator of those debates — the participants included Brad DeLong, John Cochrane, Scott Sumner, Nick Rowe, Steve Williamson, David Andolfatto, Mark Thoma, and a whole lot of other smart folks. I don’t know that we solved any of the big puzzles of macroeconomics, but we went back and productively revisited a lot of basic ideas that had mostly been out of the limelight since the 1980s. In the process, a lot of regular people outside the profession got to learn a little bit about macro debates and theories.

The Macro Wars mostly came too late to affect the policy response to the Great Recession (though it’s possible that the Fed’s third round of quantitative easing was at least partly inspired by Scott Sumner’s idea of NGDP targeting). But when Covid came around, the U.S.’ immediate and vigorous policy response probably did owe something to those old debates from 2011 and 2012. America wasted no time sending a massive flood of government money out the door in 2020-21, and the result was probably a more rapid recovery than other countries experienced (along with faster inflation in 2021).

By 2020, American elites had generally accepted that A) a deep recession needed a strong demand-boosting policy response, and B) fiscal and monetary policy were both important. That conventional wisdom didn’t come from academic papers. It came from the experience of the Great Recession, but I think was deeply shaped by the way Krugman and other bloggers had framed the outcomes and challenges of that earlier era.

One thing that made Krugman essential to these debates was his talent for explaining complex ideas in a way that was simple enough to understand but complete enough to apply. In addition to being a great researcher, he’s also a great educator — his introductory economics textbook, co-authored with his wife Robin Wells, is one of the most popular in the world. And he constantly brought that talent to bear in his popular writing. I never saw him fall into the trap of talking down to his readers, or cite his own authority as a Nobel-winning economist. Nor did he retreat into abstruse language that only other academics would understand.

Instead, Krugman took a page from Richard Feynman, who once declared that “If you can’t explain something in simple terms, you don’t understand it.” Krugman’s explanations always read like attempts to clarify his own thinking.

One example I particularly enjoyed was Krugman’s 2011 explanation of why gold should go up in value over time, and why a fall in inflation expectations should raise gold prices:

“(Yes, it’s 4:30 AM where I am. I found myself wide awake, thinking about gold prices. You got a problem with that?)

“As some readers and correspondents love to point out, you would have made a lot of money if you’d bought gold early in [the Great Recession]. So doesn’t that vindicate the [people who think inflation is going to get really high], to some extent?…

“Well, I’ve been thinking about it — and the answer surprised me: soaring gold prices may be quite consistent with a [deflationary] story about the economy.

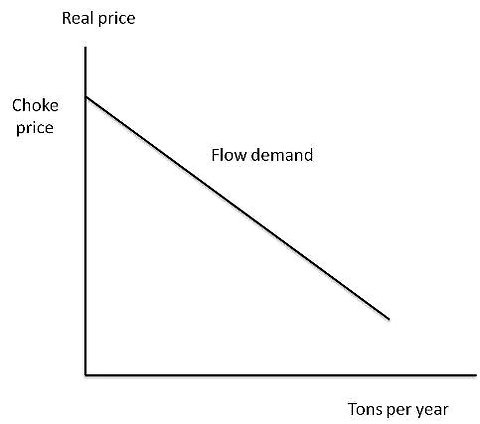

“OK, how do we think about gold prices? Well, my starting point is the old but very fine analysis by Henderson and Salant (pdf), which was actually the inspiration for my first good paper, on currency crises…Here’s how it works. Imagine that there’s a fixed stock of gold available right now, and that over time this stock gradually disappears into real-world uses like dentistry…The rate at which gold disappears into teeth — the flow demand for gold, in tons per year — depends on its real price:

“Crucially…there is a ‘choke price’ — a price at which flow demand goes to zero. As we’ll see next, this price helps tie down the price path.

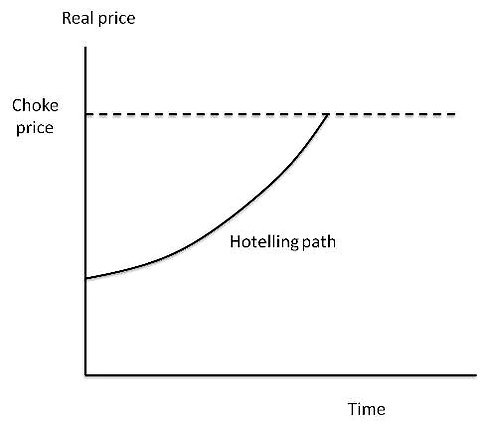

“So what determines the price of gold at any given point in time? Hotelling models say that people are willing to hold onto an exhaustible resources because they are rewarded with a rising price. Abstracting from storage costs, this says that the real price must rise at a rate equal to the real rate of interest, so you get a price path that looks like this:

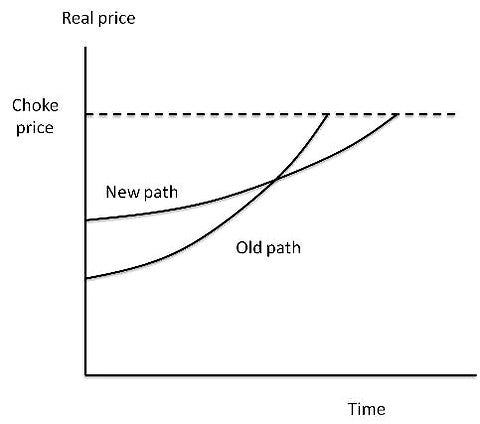

“…Now ask the question, what has changed recently that should affect this equilibrium path? And the answer is obvious: there has been a dramatic plunge in real interest rates…What effect should a lower real interest rate have on the Hotelling path? The answer is that it should get flatter: investors need less price appreciation to have an incentive to hold gold.

“But if the price path is going to be flatter while still leading to consumption of the existing stock — and no more — by the time it hits the choke price, it’s going to have to start from a higher initial level. So the change in the path should look like this:

“And this says that the price of gold should jump in the short run…The logic, if you think about it, is pretty intuitive: with lower interest rates, it makes more sense to hoard gold now and push its actual use further into the future, which means higher prices in the short run and the near future.

“But suppose this is the right story, or at least a good part of the story, of gold prices. If so, just about everything you read about what gold prices mean is wrong…

“[This] is not, repeat not, a story about inflation expectations. Not only are surging gold prices not a sign of severe inflation just around the corner, they’re actually the result of a persistently depressed economy stuck in a liquidity trap — an economy that basically faces the threat of Japanese-style deflation, not Weimar-style inflation. So people who bought gold because they believed that inflation was around the corner were right for the wrong reasons.

“And if you view the gold story as being basically about real interest rates, something else follows — namely, that having a gold standard right now would be deeply deflationary. The real price of gold ‘wants’ to rise; if you try to peg the nominal price level to gold, that can only happen through severe deflation.”

This is really an incredible little post. First of all, it’s about something that a lot of people can easily comprehend — the price of gold. It uses a simple econ model — something anyone who took Econ 101, or even just anyone who knows how to read a graph — can understand without too much difficulty. Krugman doesn’t talk down to his readers — he’s not afraid to show them a graph or three, or use words like “choke price”. But he boils down that model to the point where you can grasp it with just a few super-simple graphs and a few paragraphs of simple text.

And yet the model he shows you can make real predictions, both about financial asset prices and about the real economy. It tells you that a rise in gold isn’t a good predictor of inflation. This prediction was borne out by reality — inflation failed to rise in the years after gold went on a tear in 2004-8, but rose strongly in 2021-22 right after gold stagnated. Krugman’s model also says that the price of gold should move in the opposite direction of interest rates; this prediction came true throughout the 2010s, but has failed during the rate hikes of 2022-present. So no, we don’t have a complete theory of gold prices. But Krugman’s little toy model did pretty well!

Krugman has written a lot of great posts, but somehow this obscure little effort might be my favorite of all.

The most important and famous example of Krugman’s explanatory power, of course, was his “Babysitting co-op” story, which he wrote in an article for Slate in 1998. Krugman uses the story of a babysitting co-op that fails to issue enough coupons to explain how a demand-side recession results from a shortage of liquid assets, and why monetary easing can stimulate the real economy. Note that he was thinking about these ideas in public, ten years before Lehman Brothers failed:

“[S]uppose that the U.S. stock market was to crash, threatening to undermine consumer confidence. Would this inevitably mean a disastrous recession? Think of it this way: When consumer confidence declines, it is as if, for some reason, the typical member of the [babysitting] co-op had become less willing to go out, more anxious to accumulate coupons for a rainy day. This could indeed lead to a slump—but need not if the management were alert and responded by simply issuing more coupons…Even if the head coupon issuer has fallen temporarily behind the curve, he can still ordinarily turn the situation around by issuing more coupons—that is, with a vigorous monetary expansion…So as I said, the story of the baby-sitting co-op helps me remain hopeful in times of depression.”

This general idea — the importance of aggregate demand — ended up becoming the most important idea that Krugman ever injected into the public consciousness. Krugman’s academic research isn’t actually about Keynesian macroeconomics — it’s about other stuff like trade, geography, urbanization, and development. But all the way back in the late 90s, Krugman was looking at Japan’s bubble burst and “lost decade”, and thinking about how to explain what had happened there. His answer was that Japan was in a liquidity trap — a persistent shortage of aggregate demand that occurs when nominal interest rates go to zero, and conventional monetary policy loses its potency.

When the Great Recession hit America, Krugman saw a very similar situation unfolding. A financial crisis caused a shortage of demand, and interest rates hit zero and could go no lower. So Krugman called for major fiscal stimulus and quantitative easing to boost demand back to where it should be, citing both classic and recent Keynesian models as his justification. That call was resisted by a large number of people — hard-money types who feared inflation, conservatives who feared that stimulus spending would become permanent, orthodox economic theorists who thought recessions aren’t even worth fighting in the first place, monetarists who were skeptical of fiscal policy, and so on.

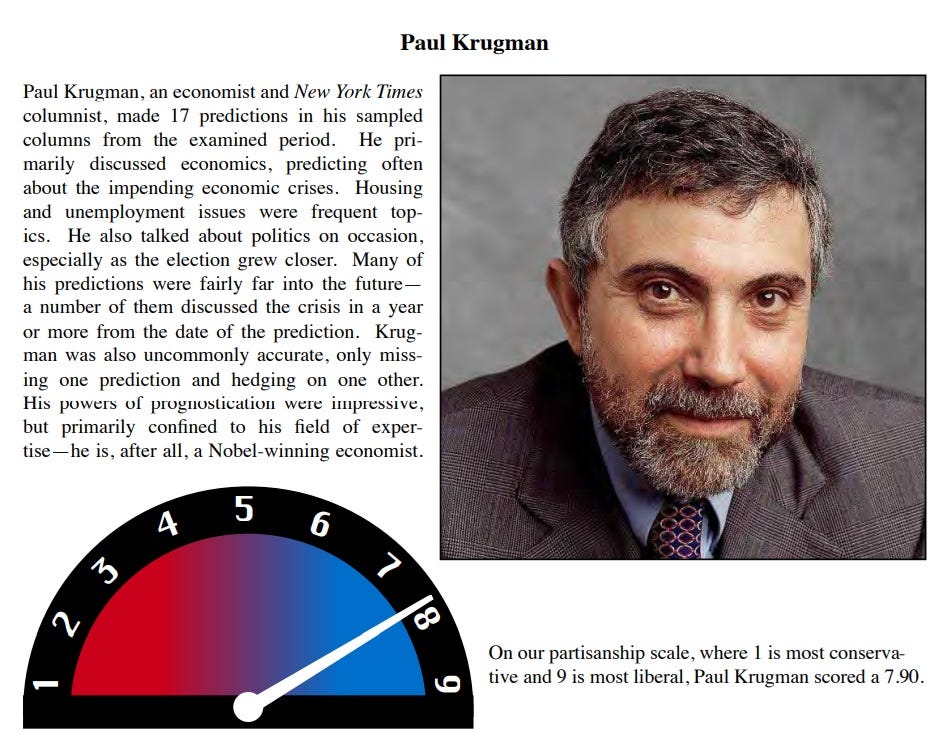

Krugman took them all on, one by one, day after day. I once joked that Krugman was like the 1980s cartoon robot Voltron, taking on a new enemy every week — goldbugs, Austrians, classical economists, libertarians, and hard-money people of all varieties — and predictably coming out on top each time. In fact, a research paper by some students at Hamilton College tested predictions by pundits, and found that Krugman was the most accurate out of the bunch:

KrugTron…er, Krugman argued that his success in these debates was due to his opponents being blinded by their conservative politics. My own guess was that Krugman benefitted from using 1990s Japan as a model. But the truth is probably just that Krugman recognized the importance of aggregate demand in a situation like the Great Recession. Simple, classic Keyensian ideas are still the best thing we’ve got.

But another of Krugman’s great strengths as a pundit was his open-mindedness and mental flexibility. He kept hammering home the idea of aggregate demand and fiscal stimulus during the early 2010s. But when Covid came around in 2020, he correctly realized that the country was facing a very different kind of shock. When I interviewed Krugman for Bloomberg in May of that year, he argued that we would bounce back much more quickly than in the Great Recession. Some excerpts from his part of that interview:

“The aggregate-demand-aggregate-supply framework doesn’t work well for this crisis…What’s happening now is that we’ve shut down both supply and demand for part of the economy because we think high-contact activities spread the coronavirus. This means we can’t just use standard macro models off the shelf.

“But…Even though this crisis is really different from anything we’ve seen before, my sense is that we’ve got a pretty good handle on the economics. In particular, we know enough to understand why conventional responses like stimulus or tax cuts are inappropriate, and why we should be focusing on safety-net issues…

“My take is that the Covid slump is more like 1979-82 than 2007-09: it wasn’t caused by imbalances that will take years to correct. So that would suggest fast recovery once the virus is contained…[R]ight now I don’t see the case for a multiyear depression. People expecting this slump to look like the last one seem to me to be fighting the last war.”

That sort of mental flexibility and objective analysis is very rare in pundit-land, and it’s less common in academic economics than one might like. So it was pretty impressive to see Krugman respond to a new crisis by tossing out his old analytical framework, finding more appropriate models from the literature, and making completely different recommendations and predictions from the last time around. And getting it all right, once again.

Of course, Krugman didn’t always get everything right. In 2021, he predicted that the post-pandemic inflation was mostly due to transitory supply disruptions, rather than to fiscal and monetary policy; when inflation failed to go away, Krugman admitted he had messed up. Ironically, it was Olivier Blanchard — whom Krugman had dinged back in 2009 for neglecting the importance of fiscal policy — who used a simple Keynesian multiplier and Phillips curve analysis to predict substantial inflationary effects from Biden’s 2021 Covid relief bill. Standard classic Keynesian models, of the type Krugman constantly stumped for during the Great Recession, did still work after all.

So all in all, what was Paul Krugman’s impact on the public face of economics? Along with Tyler Cowen, he defined what economics blogging ought to look like — the rest of us, to a large extent, are still just following the formula he pioneered. He managed to reintroduce and popularize Keynesian macroeconomics, both inside and outside the econ profession. And he educated the public on a wide variety of interesting econ theories and empirical results. In Cowen’s assessment, Krugman — in his public-facing incarnation — was the closest thing to a Milton Friedman for the modern age.

But unlike Friedman, Krugman never integrated his whole worldview into a coherent paradigm. Friedman’s worldview incorporated monetarist macroeconomics, neoclassical microeconomics, libertarian values and politics, and various notions of political economy — it all fit together into a paradigm, which deeply informed the economic approaches of Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher, possibly Deng Xiaoping, and even some modern-day leaders like Javier Milei.

Krugman, in contrast, never created his own world-encompassing paradigm. He has made no secret of his left-leaning politics, and his support for the Democratic party is staunch. There was at least one protester at Occupy Wall Street with a sign reading “Krugman’s Army”. But his econ writing has always focused on isolated topics of interest instead of trying to build an overarching framework; even his advocacy of Keynesian economics was fairly narrow.

Krugman had the rhetorical skill, the technical brilliance, and the ideological credibility to create a new progressive political-economic paradigm — a complete answer to the “neoliberalism” created by Friedman and his contemporaries. But he chose not to, leaving that task to others like Joseph Stiglitz, James K. Galbraith, and Robert Reich. I can tell you a bunch of things Krugman believes, but I can’t really tell you what “Krugmanism” is.

In my view, this is much to Krugman’s credit. Cohesive political-economic worldviews are powerful tools in the hands of their creators, but tend to crystallize into ideological straitjackets as soon as others try to apply them. And all ideologies eventually overreach. The flaws of Friedmanism are so well-known that I don’t have to go over them again, and even just a few years in we’re already starting to see the cracks in the progressive alternative that folks like Stiglitz have whipped up.

Of all Krugman’s approaches to economics writing, this is the one I most want to emulate. Punditry isn’t science, but I believe there are approaches from science we can benefit from. Chief among those is what Richard Feynman called the “freedom to doubt” — the insistence on using our curiosity as our primary tool of seeking truth, instead of our ideologies. It was curiosity that had Paul Krugman up at 4:30 AM writing a post about gold prices. It was curiosity that led him to think about the importance of liquidity traps and aggregate demand ten years before almost anyone else realized they mattered. With Krugman, the ideas always came first, and that’s perhaps the biggest reason his shoes will be so hard to fill.

This article was originally published in Noahpinion and is republished here with permission.