As we stop having kids, do we still need real estate developers?

Regular Thesis Driven readers know that I’m as pro-housing as they come. Home prices and rents in the places with the most economic opportunity—like New York and San Francisco—are a national scandal, and I’m very much in favor of legalizing more housing to combat rising costs.

But one of the most alarming macro trends of the past decade has been the worldwide fertility collapse which has led to rapid downward revisions of both national and global population growth estimates. With a total fertility rate of 1.6 children per woman (versus a replacement rate of 2.1), the US is now entirely dependent on immigration to maintain its population—immigration that is as politically unpopular as it has ever been.

It’s possible that the next decade will bring us a shrinking America. In that context, it’s worth asking: will we still need to build things?

Today’s letter will explore the population crunch from a real estate perspective. Specifically, we’ll tackle:

- How the global population crunch is materializing;

- Politics and population projections;

- Examples from around the world, including many nations far worse off;

- Implications for the real estate industry across sectors and predictions of when problems may start materializing.

A Global Local Problem

Writing about global population change is challenging for a few reasons. One, the data available is often imperfect. In the US, for instance, undocumented migration—and the fact that recent migrants tend to avoid census workers—has made estimating the number of people in the country challenging. And the US is a relatively easy case; it’s likely that population data for some African countries are wildly wrong. (If one were to generalize, it’d be that US population is probably underestimated and global population is probably overestimated, but we can ignore that for now.)

But writing about population is also hard because it’s a global problem with highly variable local implications. The US population as a whole could be declining, but if people are still moving to Los Angeles, the LA real estate market might do just fine.

Caveats aside, the overall trend lines are clear: population growth is declining far faster than expected.

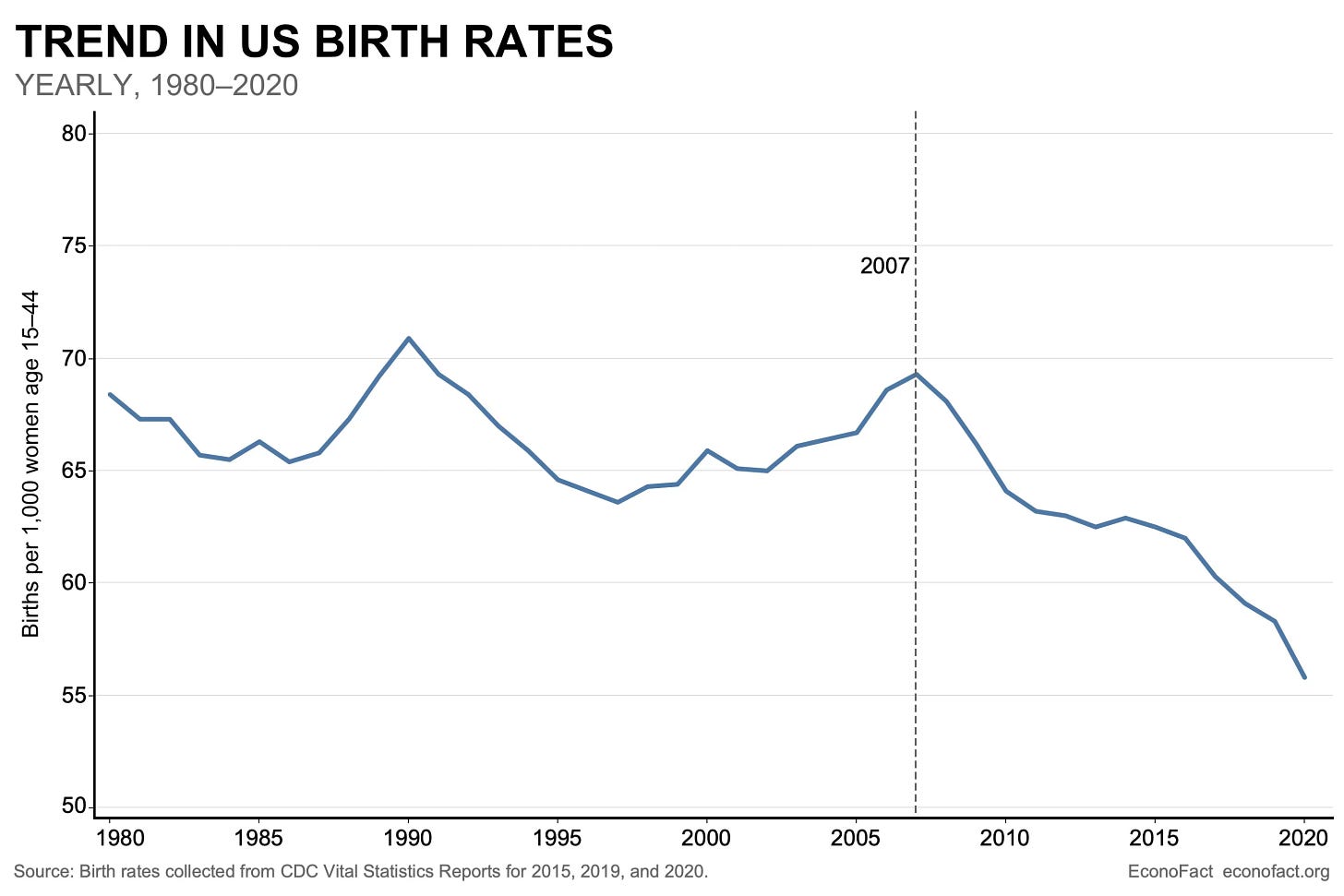

This is not a new thing; population growth has been slowing in the US since end of the postwar Baby Boom. But the years since the GFC have been particularly bad for birth rates, which were hanging on around replacement rate until cratering after 2010.

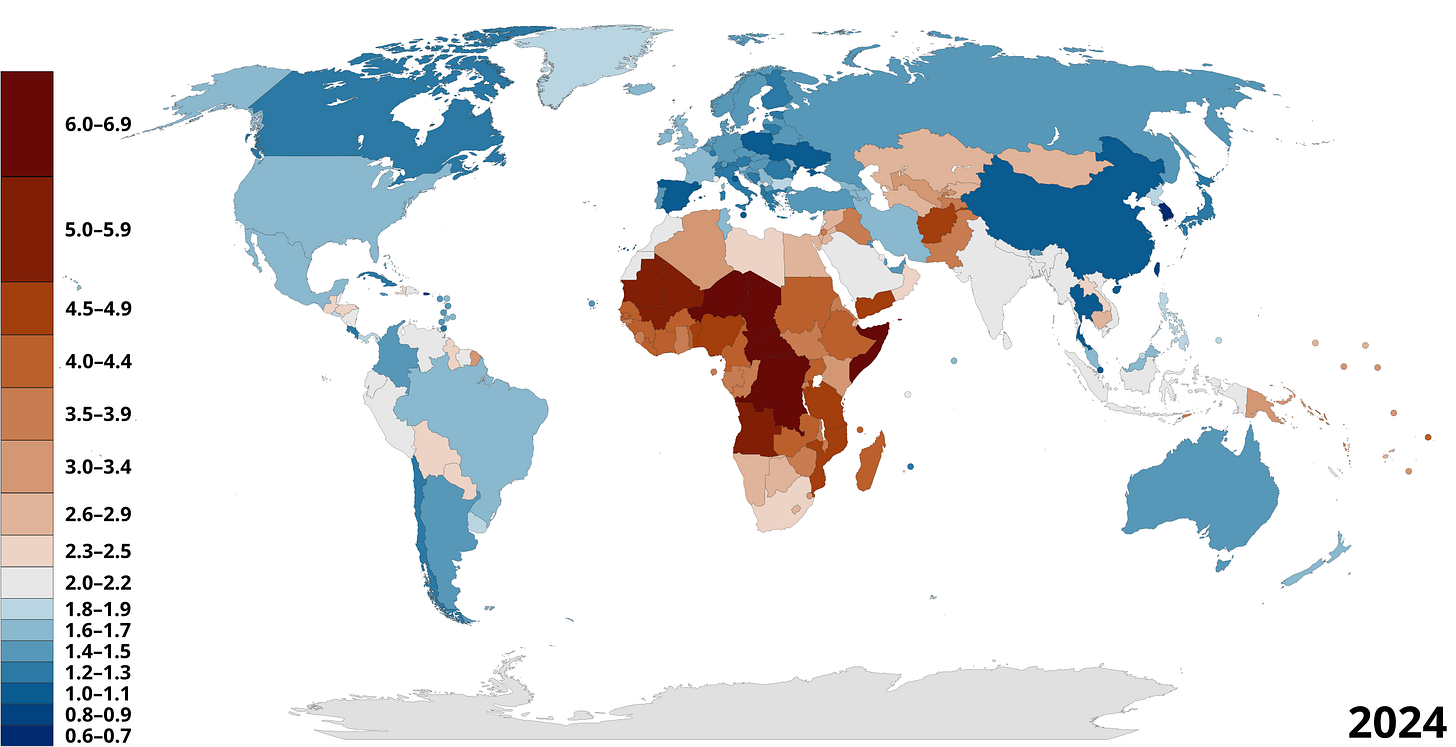

It’s worth noting that, despite this rapid decline in fertility, the US is in relatively good shape in comparison to its developed peers. Some countries, particularly in Eastern Europe and East Asia, have terrifyingly low birth rates. With a TFR of 0.72, South Korea is staring down a demographic catastrophe in the back half of the 21st century. China isn’t much better off, perhaps putting pressure on them to shake up the geopolitical landscape sooner rather than later. While Western Europe is holding up slightly better, no single country is above replacement rate.

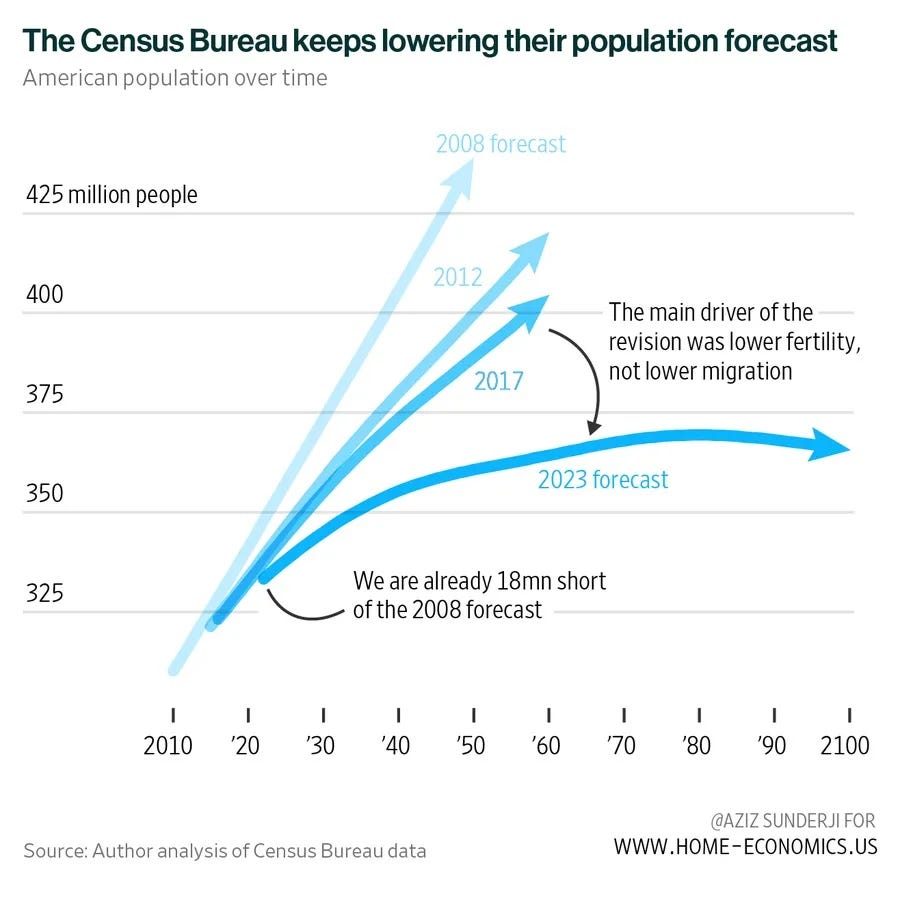

The US’s rapidly declining birth rates have led the Census Bureau to repeatedly revise estimates of the US population downward. As of latest forecast, even with immigration the US population will never reach 375 million, with growth slowing significantly in the 2030s as the Baby Boomer generation dies off before finally plateauing after 2060.

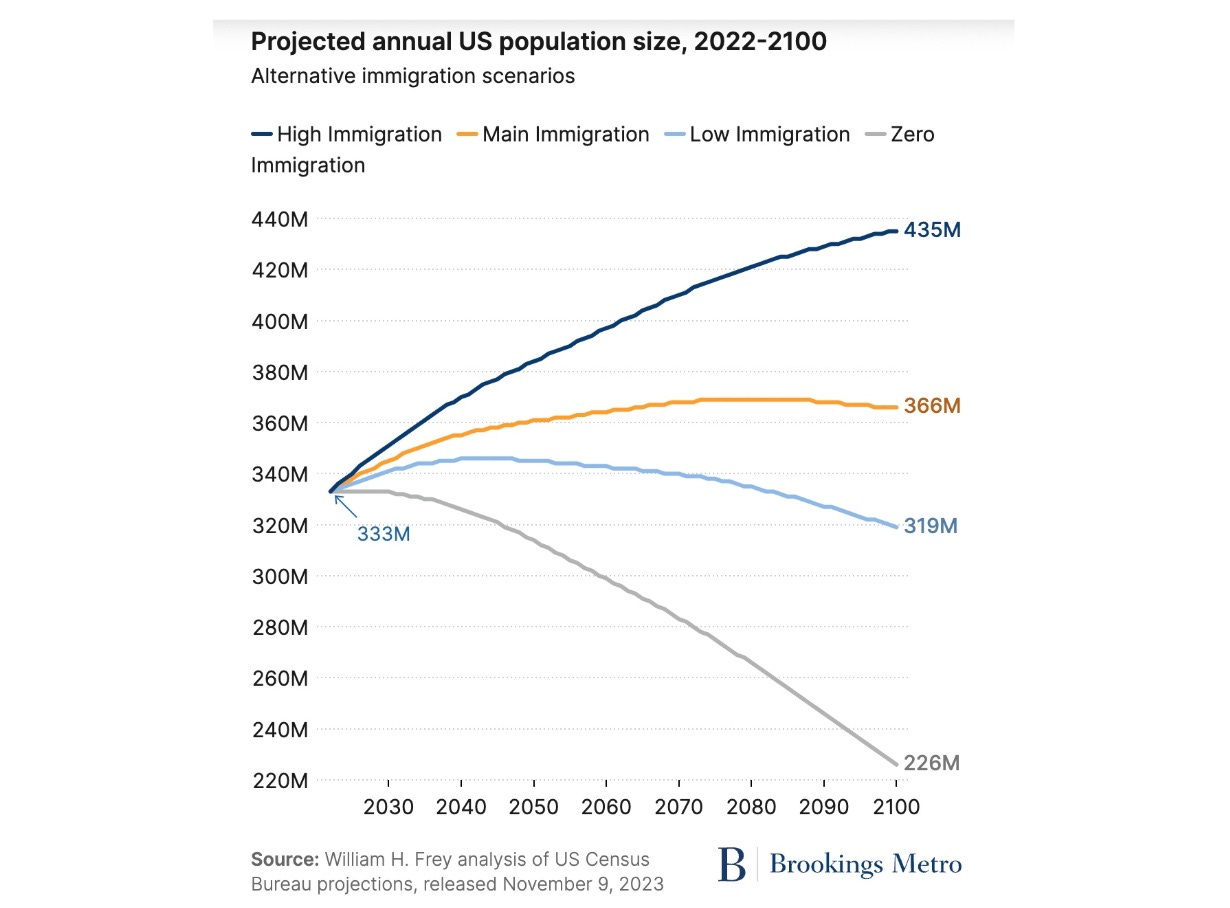

Many economists believe that the US’s demographic struggles can be staved off with immigration. And for sure, immigration plays an important role in maintaining the country’s population today—without it, the US would be shrinking and on track to have two-thirds as many people by 2100.

But there are two reasons to be skeptical of immigration as the answer.

One, immigration is historically unpopular. As of last June, 55% of Americans believe we should have less immigration versus only 16% advocating for more—the highest delta in more than 20 years. And the current administration is likely to dramatically cut immigration levels, both legal and not. As much as economists talk up the benefits of immigration, voters just aren’t buying it.

But the larger reason why immigration might not be the answer is that birth rates are falling everywhere, and fast. Many countries seen as steady growth machines have recently sagged below replacement rate with little sign of recovery. Turkey, Iran, Brazil, and even India and Indonesia are now experiencing sub-replacement rate fertility. Outside of Africa, the number of countries with birth rates above replacement can almost be counted on two hands.

Even Africa is experiencing dramatic declines in fertility; the continent dropped from almost 7 births per woman in 1980 to only 4.1 today. Economists estimate that sub-Saharan African will also drop below replacement rate fertility around 2070.

(Note that for many of these countries, sub-2.1 TFR doesn’t necessarily mean population declines, as improvements in sanitation and medicine mean people live longer. But that’s simply kicking the can down the road; in the absence of immigration, sub-2.1 TFR will eventually lead to shrinkage.)

Compounding the problem is that birth rates are largely uncontrollable as a matter of policy. No intervention—from free childcare to tax incentives to direct payments—seems to make a difference. Among developed countries, only one—Israel—has a birth rate above replacement. When countries get wealthy, people simply lose interest in having kids, and institutions appear powerless to change that.

So in a shrinking world, what becomes of the real estate industry?

A Local Global Problem

At risk of stating the obvious, population growth is the most important long-term indicator of real estate demand. Developers and investors want to bet on places that are growing and avoid places that are shrinking. When buying and building real estate, betting on assets in the path of growth can forgive many mistakes.

It’s important to note that a shrinking country would not shrink uniformly, so “growth is going away entirely” isn’t the right conclusion. But it’s probably fair to say that a shrinking country would have fewer areas of growth and far more places in which there just simply aren’t enough humans to take up all the real estate that already exists.

While it’s tough to pick geographic winners and losers, the places with the greatest housing shortages today—and correspondingly high rents—are likely to weather the storm better than places with lots of supply and wobbly rents. If NYC’s eye-watering rents drop by 20% (the average Manhattan 1BR is $4,956), lots of people who always wanted to live in New York City are likely to make the leap, lending some stability to prices and occupancy. The same cannot be said for other places that might just run out of people who want to live there, potentially setting off a death spiral of depopulation driving less demand from employers and retailers driving further depopulation. This is particularly true for rural and Rust Belt towns with demand primarily coming from first-generation immigrants today.

But shrinking population doesn’t necessarily mean zero real estate development. New office projects are still breaking ground in 2025 because there are pockets of significant demand for the right office products—Class A+ and boutique assets in “neighborhood” locations, mostly—despite far less demand for the asset class writ large. “Demand” isn’t a monolithic concept just as real estate isn’t a monolithic asset class; it’s totally reasonable for one subcategory or market to boom even as the market as a whole pulls back.

Shrinking cities today, after all, still have some real estate development activity. The Detroit metro, for example, permits about 400 new homes per month despite losing 1% of its population since 2020. But these projects are often unsustainable sprawl, new greenfield developments poaching a dwindling pool of residents from existing, aging housing stock. In many cases, this leaves entire neighborhoods hollowed out and cities holding the bag of legacy infrastructure maintenance.

On the surface, this is a dire picture for the future of real estate. But the reality of the next few decades will be somewhat more complicated.

Timing the Crest

The urgency of this problem largely depends on how aggressively the Trump administration cuts immigration and how lasting those cuts will be. A Brookings report from 2023 highlights immigration’s key role, painting diverging pictures of US population ranging from continued steady growth through 2100 (high immigration) to immediate stagnation and shrinkage (no immigration).

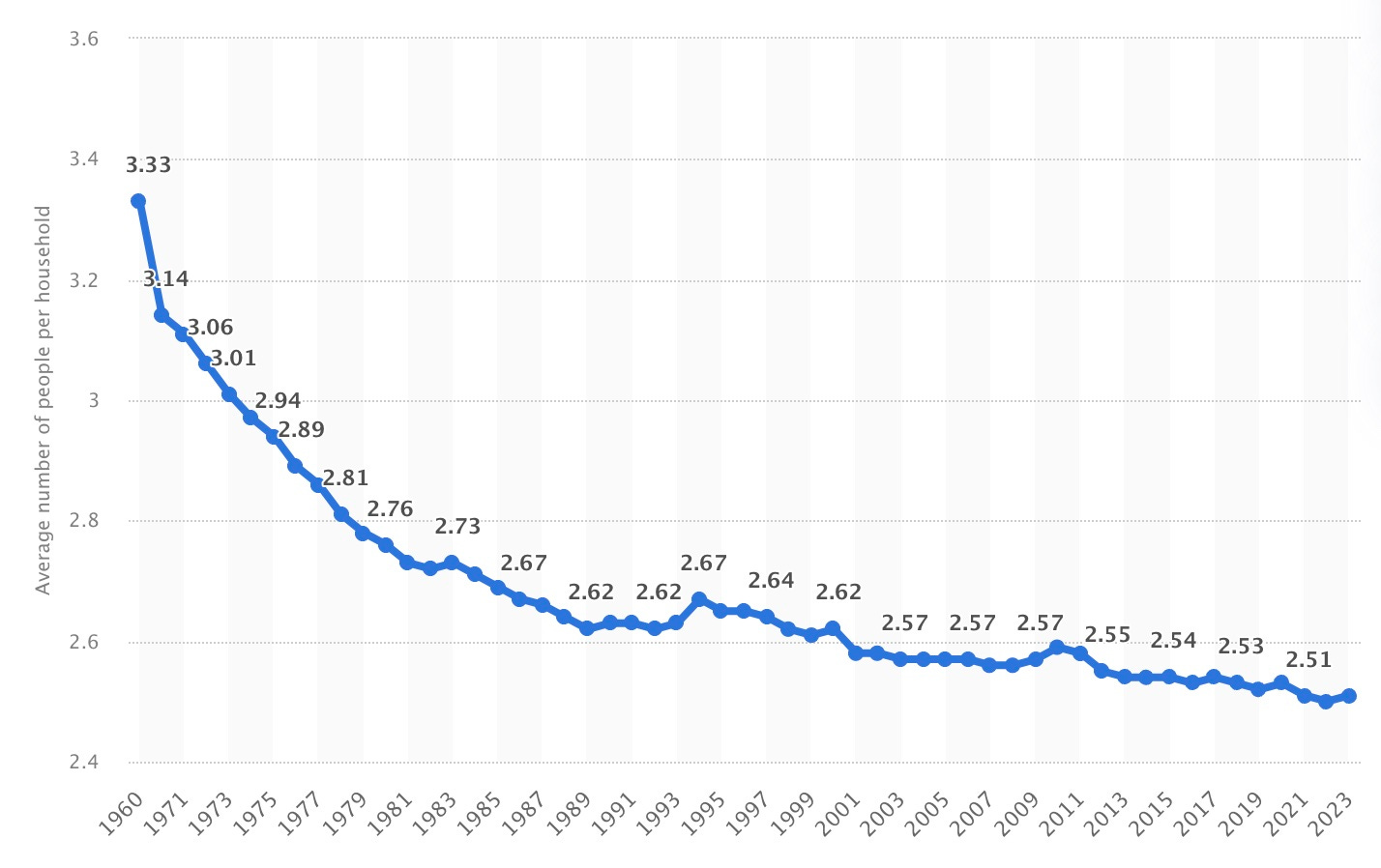

From a real estate perspective, household size is the other key variable. Household size has been steadily ticking down for about as long as humans have been around, and the average household size currently sits around 2.5 people per household. (Housing shortage skeptics like to point to the US having a growing number of homes per capita to claim we have plenty of homes, neglecting to adjust for declining household size.)

The question is how elastic household sizes really are. If we had fewer people, there would be less demand for real estate, dropping rents. How far rents drop depends on how much lower rents encourage new household formation.

Currently, 57% of 18-24 year olds and 22% of 25-29 year olds live with their parents, slightly off 2020 peaks but still close to the highest levels since the Great Depression. It’s very likely that, given the choice, many of these young people would live on their own but simply can’t afford the rent. If rent were to drop, say, $200 per month, it’s likely that some number of young people would break off on their own sooner, supporting housing demand and stabilizing rents.

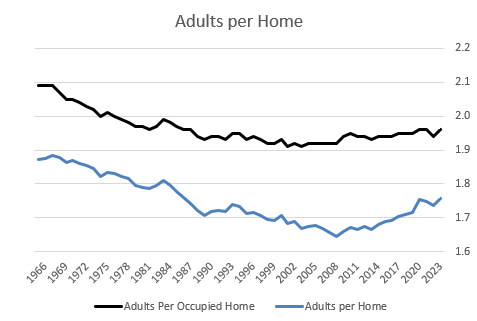

This pent-up demand shows up in the data in other ways, too. Despite a record number of single-person households, the number of adults per home has actually increased over the past 20 years. This is likely the effect of more adult children living with their parents.

Housing writer Kevin Erdmann estimates that getting back to 2008-era levels of adults per home would require 11 million new units:

“[…] you can see that even adults per household has risen since 2008. So, homes per capita is at all time highs because of the declining number of children. Adults per household bottomed at 1.91 and has increased up to 1.96. In other words, homes per adult is not at all-time highs.

“Returning adults per occupied home to 1.91 would call for about 4 million units itself.

“But, remember, many of the new households were occupying formerly vacant units. Vacancies are far too low now. Adults per home bottomed out at about 1.65 and has risen back up to 1.76. Getting that back to the pre-2008 level would require about 11 million homes.“

So even if population were to suddenly stagnate—Brookings’ “no immigration” scenario—the US would still need a lot more homes to make up for almost two decades of underproduction.

Slow Crash

In other words, there is no immediate downfall on the horizon for the US real estate industry. Even in the tougher, low-immigration scenarios, pent-up household formation will likely keep rents and housing demand strong for at least the next decade or two.

But more fundamental assumptions about the value of holding real estate long-term deserve a hard look. We’ve been trained to view real estate as a great long-term asset; we revere those who purchased real estate decades ago for peanuts only to see it appreciate to create generational wealth today.

That natural appreciation, however, was always predicated on growth. The supply of land is fixed, and if more people and wealth are pursuing a fixed supply of land, the price of that land will go up. Long-term appreciation of real estate isn’t an inherent natural force; it’s downstream of supply and demand. While real estate assets have generally appreciated faster than inflation over the past 75 years, that can’t be said for real estate in shrinking places like St. Louis, Detroit, or the ArkLaMiss. And the next 50 years will see that kind of decline become the norm while booming metros are fewer and farther between.

All this means that real estate investors will have to work smarter, making informed bets on specific places likely to see sustained growth. An allocator-like portfolio approach just might not work in a world where each generation brings a smaller pool of potential renters, employers, and buyers. And cities would be wise to adopt business-friendly policies that proactively encourage growth and development before it’s too late.

A surge of immigration over the past several years has allowed the real estate industry to ignore some hard demographic realities. But with new management at the helm, a shrinking America may be upon us sooner than we all thought.

This article was originally published in Thesis Driven and is republished here with permission.