More thoughts on a great civilization at its peak.

“We are amazed, but not amused” — Stevie Wonder

The 20th century had a bunch of rising powers that all reached their peaks in terms not just of relative military might and economic strength, but of technological and cultural innovation. These included the United States, Japan, Germany, and Russia. So far, the 21st century is a little different, because only one major civilization is hitting its peak right now: China. All the old powers are declining, and India is just beginning to hit its stride.

China’s peak is truly spectacular — a marvel of state capacity and resource mobilization never seen before on this planet. In just a few years, China built more high-speed rail than all other countries in the world combined. Its auto manufacturers are leapfrogging the developed world, seizing leadership in the EV industry of the future. China has produced so many solar panels and batteries that it has driven down the cost to be competitive with fossil fuels — a huge blow against climate change, despite all of China’s massive coal emissions, and a victory for global energy abundance. China’s cities are marvels of scale — forests of towering skyscrapers lit up with LEDs, cavernous malls filled with amazing restaurants and shops selling every possible modern convenience for cheap, vast highways and huge train stations. Even China’s policy mistakes and authoritarian overreaches inspire awe and dread — Zero Covid failed in the end, but it demonstrated an ability to control society down to the granular level that the Soviets would have envied.

But it’s still an open question whether China will be as creative as the great civilizations of the 20th century. Many people (including myself) compare early 21st century China to early 20th century America. But by the start of World War 1, Americans had already invented the airplane, the light bulb, the telephone, the record player, air conditioning, the automatic transmission, the machine gun, and the ballpoint pen. And the country had already given rise to jazz music, Hollywood movies, and lots of well-known literature. Japan’s cultural explosion came a bit later, but was every bit as impressive.

It’s pretty obvious that an autocratic, repressive government stifles cultural creativity. I still expect China’s cultural exports and influence to increase as time goes on, due to increased personal wealth and leisure time that make Chinese people feel more free to pursue artistic interests. But everything in the country is heavily censored, which means that the movies and music and video games and TV and art that come out of China will usually tend to be bland, anodyne stuff.

It’s much less clear whether scientific and technological creativity suffers from autocracy, though. Autocrats want to develop science and technology to make their countries strong. They sometimes squelch private entrepreneurs out of fear that an alternative center of power would threaten their rule, but at the same time they tend to direct large amounts of resources toward research and development. The USSR beat the U.S. to space (twice), and Germany was pretty autocratic for most of its run as the world’s leading scientific and technological powerhouse.

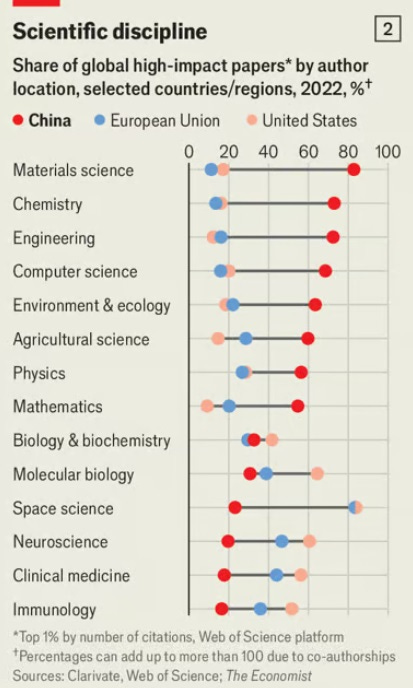

Modern China is certainly a very innovative country. Chinese scientists now publish the majority of high-impact papers in fields like chemistry, physics, computer science, materials science, and engineering:

The country’s true dominance is probably less than depicted in this chart, due to “home bias” in the citations used to measure papers’ impact. But even correcting for that bias, China is undeniably a scientific superpower.

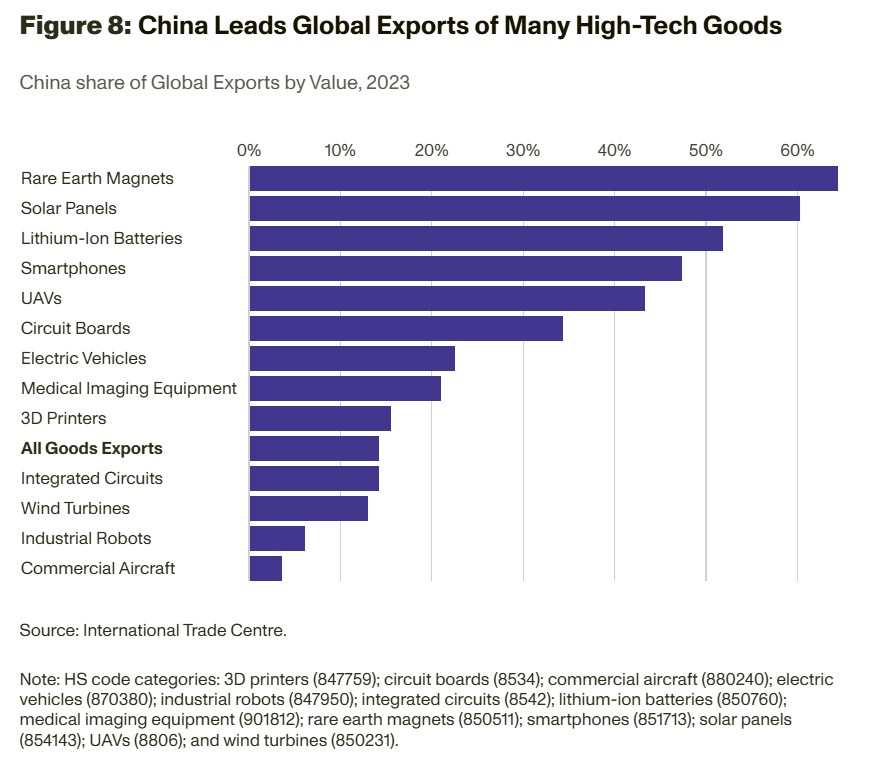

China’s innovation outside of the laboratory is just as impressive. A vast number of incremental improvements and process innovations allow many Chinese businesses to improve product quality and decrease manufacturing cost much more effectively than their foreign rivals. Without Chinese innovation, most of the manufactured goods we consume would be either lower-quality, more expensive, or both. In fact, Chinese companies are responsible for most of the nation’s research spending. As a result, Chinese companies dominate the global market for a number of high-tech products:

And in terms of deploying technologies so that people can use them, China is now ahead of most or all of the rest of the world. It has the world’s biggest high-speed rail system, one of the world’s best 5g cell phone networks, the world’s best mobile payments system, the world’s best delivery robots, some of the world’s most automated factories, and the world’s most futuristic cars.

But in terms of actual big scientific and technological breakthroughs — game-changing inventions, theories, and empirical findings — what has China produced in its golden age so far? The answer to this question might not be economically important — it’s hard to name an invention that came out of Singapore, and yet it’s among the richest countries on Earth. But it’s kind of an interesting question nonetheless.

Now, some people argue that big breakthroughs are just less common than they used to be. Some believe the low-hanging fruit of science has already been picked. It’s also possible that the much greater competitiveness of today’s global scientific enterprise and today’s global economy mean that it’s harder for a single inventor or discoverer to get far ahead of the pack. Nevertheless, we have seen a bunch of big breakthroughs and game-changing inventions in the last two decades — AI, generative AI, mRNA vaccines, Crispr, smartphones, reusable rockets, lab-grown meat, self-driving cars, and so on. And it’s usually not too hard to identify a few researchers or a single company that made the big breakthrough for each one of these.

So what big ones have come out of China in the last decade and a half? First of all, I think it’s helpful to differentiate three different types of breakthrough innovation:

- Scientific discovery: This is when someone either finds some important empirical result, or invents a new useful theory.

- Prototype invention: This is when someone demonstrates some technological functionality in a lab setting.

- Commercial invention: This is when a company creates a version of a technology that has sufficient functionality to achieve mass commercialization.

The line between 1 and 2 isn’t especially important in my opinion, but the difference between 2 and 3 is the source of many arguments about who invented what. James Watt didn’t build the first working steam engine, nor Apple the first working smartphone, but they made critical improvements that made those technologies mass-marketable in forms that would be recognizable many years later. This leads some people to say that Watt and Apple don’t deserve the credit for these inventions, but I think they’re wrong. Successful commercial invention requires bringing together a set of features, functional improvements, cost reductions, design, marketing/branding, and a business model for selling the thing, and so it involves a different set of skills than making a prototype in a lab.

On the other hand, prototype invention is clearly important as well, because it demonstrates that something is possible to build. Everyone recognizes the Wright Brothers as the inventors of the airplane, even though they didn’t make the kind of plane that a bunch of people wanted to buy and use.

So anyway, I tried to look up the answer to this question. My sources include Wikipedia’s lists of Chinese inventions and discoveries, Google searches, a conversation with Glenn Luk (who is very bullish on Chinese innovation), and a report by ChatGPT’s “Deep Research” AI.

In terms of commercial inventions like the smartphone or the steam engine, there are some big things that have come out of China since the turn of the century. These include:

1. The quadcopter drone

When people say “drone” these days, they usually don’t mean things like America’s Reaper or Iran’s Shahed — things that run on fossil fuels. They mean battery-powered quadcopters. This type of drone has transformed our physical world much more than any other — arguably more than any piece of tech since the smartphone — and seen much wider commercial adoption.

The first electronic remote-controlled quadcopter drones were built by a Canadian company called Draganfly in the 1990s. A French company called Parrot released the first commercially successful quadcopter in 2010. But it wasn’t until China’s DJI released their Phantom in 2013 that drones attained the baseline level of functionality we expect from them today, and took off as a popular global product. DJI’s drones had better control, more stability, and longer flight time than Parrot’s, as well as a number of additional features that we now see as crucial.

So I think it’s probably fine to call DJI’s founder Frank Wang (pictured at the top of this post) the inventor of the modern quadcopter drone, in the same way that Steve Jobs is generally regarded as the inventor of the iPhone.

2. 5G wireless communications

5G isn’t one thing — it’s a product standard, meaning it’s a suite of various wireless technologies and capabilities. But Chinese companies, especially Huawei and ZTE, led the world in terms of the integration of those various technologies. Those companies brought together technologies like Massive MIMO (a technique for using multiple antennas), beam forming (a way to transmit wireless data more directly and efficiently), and polar codes (a technique for noise reduction), they optimized and improved on these technologies, and they rolled them out effectively to consumers.

So I think it’s fair to say that Chinese companies “invented 5G” in the same sense that Japanese companies invented 3G, or American companies invented 4G.

3. The personal air taxi

Lots of companies have been working on these, but most people agree that the Chinese company Ehang was the first to commercialize these. They look pretty nifty:

4. The semi-solid state battery car and the sodium-ion battery car

Chinese car companies were the first to release vehicles powered by semi-solid state batteries and sodium-ion batteries, two alternatives to the typical lithium-ion batteries we use in EVs. Each one offers some tradeoffs relative to the typical kind of electric car — sodium-ion batteries are a bit safer and charge faster, while semi-solid batteries have faster charging, better safety, higher energy density, and longer lifespans.

5. Dockless bike sharing

Bike sharing itself was invented elsewhere, but a Chinese company is generally believed to be the first to commercialize dockless bike sharing, which has now become widespread in the country.

6. The foldable smartphone

The Royole FlexPai is generally acknowledged as the world’s first commercialized foldable smartphone. It’s pretty neat!

7. Face-scan payments

China’s Alipay was the first to implement “smile to pay” systems, back in 2017.

8. The vape (e-cigarette)

This was actually invented back in 2003, by a Chinese pharmacist named Hon Lik.

9. The skyscraper building machine (and various other construction machinery)

This is pretty awesome. A Chinese company created a machine that moves up a skyscraper as it’s constructed, building each floor as it goes:

There are also some pretty cool original machines for laying high speed rail track.

10. Electromagnetic car suspension

This was invented a long time ago by Bose, but BYD appears to be finally bringing it to market:

Those are the main commercial inventions I could find. I’m sure this isn’t a complete list, because A) there are a few things that are probably known inside of China but not well-known in English-language media yet (I’ve heard rumors that Chinese chip companies are already mass-producing 3D DRAM, for instance), and B) there are some inventions that will end up being important but whose importance people haven’t generally realized yet (like the air conditioner in 1902).

Also, this list might soon expand. Chinese companies might soon come out with the world’s first marketable humanoid robots, solid-state car batteries, vacuum maglev trains (“hyperloop”), thorium nuclear reactors, perovskite solar cells, lab-grown organs, etc. These technologies have been in development for a while, and while any one of them would represent a game-changing invention, it has never been clear how far they were from mass-market adoption.

So if you can think of anything else that should go on this list, please let me know.

But even allowing for the incompleteness of this list, I feel like I expected it to be…a little more impressive? Drones are amazing, and are already changing the world, but some of the other items here seem a little bit marginal. Dockless bike-sharing is neat, but I’m not sure how big of a difference it makes in terms of transportation convenience relative to the docked variety. Foldable smartphones are cool, but will you really buy one? Sodium-ion and semi-solid-state battery cars have some advantages, but seem likely to end up as niche products. Facial recognition payment doesn’t really save you much time versus swiping a phone, and it’s a little creepy. A couple of commonly mentioned items, like BYD’s “blade battery”, seemed so incremental that I didn’t even put them on this list.

Anyway, prototype inventions are a bit harder to identify, because unless they’re done in an academic lab, it’s hard to tell how well the prototype really works. Companies tend to be tight-lipped about what they invent, especially in China where other companies are always trying to steal their IP. And what you do see publicly released is often a marketing stunt that doesn’t really reveal how well the thing works. Then there are military inventions, which are kept under even tighter wraps. Even when you know that a Chinese company has a working prototype of a humanoid robot, or a solid-state battery car, or a vacuum maglev, it’s not clear whether they got there first in any meaningful sense.

The Wright Brothers were sort of a special case here — everyone could see for themselves that the thing flew.

As for scientific discoveries, here I’m having a lot of trouble constructing a list. The top ones I could find include:

1. The creation of space-based quantum communications (useful for telling when your communications have been compromised)

2. The first cloned primates

3. The first photonic quantum computer to demonstrate “quantum supremacy”

4. The first human babies whose genes were edited using Crispr (though the scientist was jailed for doing this)

There’s really…not much else. Not being a scientist, I’m not really able to judge how groundbreaking a discovery in chemistry or materials science or biology is. But AI, Wikipedia, and the lists I find online are having real trouble listing Chinese achievements in science that aren’t of the form “world’s biggest radio telescope” or “fastest supercomputer on Earth for six months”. Wikipedia’s list of modern Chinese discoveries is almost all math theorems from the mid 20th century (usually work done outside China).

Again, if there are big ones I’m missing, please let me know!

This is a little strange, right? Chinese scientists are publishing 80% of the world’s high-impact papers in materials science, 75% in chemistry, and almost 60% in physics, and neither I nor the entire English-speaking internet can find more than one or two breakthrough advances coming out of China in these fields?

The answer here can’t be “Chinese science is fake”. I mean, a bit of it is fake, because of citation rings and perverse incentives at Chinese universities, but most of it is very real. It’s just all incremental stuff. The weight of all those incremental discoveries is certainly world-changing, but so far there have been startlingly few big breakthroughs.

The seeming paucity of Chinese invention and discovery is even stranger when we consider how much human capital the country has. With 1.4 billion people, one of the world’s best education systems (at least in the richer regions), and incredibly well-funded universities, the country should be producing more Nobel-caliber scientists. The talent is there. Except when you hear about Chinese scientists making world-changing discoveries, they all seem to have done their work outside China, often in the U.S.

Now, I’m always very wary of the stereotype that Asian countries are uncreative. This stereotype got lobbed at Japan for a long time, but it was never true; a list of Japanese inventions and discoveries will run for many pages. Yes, there were cases in which Japanese companies adopted and improved technology from the U.S. and Europe — CNC machine tools, shipbuilding, and fuel-efficient cars come to mind — but at the same time, Japanese scientists and inventors made breakthroughs at about the same rate as their counterparts in the West. The “Japan is uncreative” trope partly came from Japan’s slightly later industrialization, but was also a defensive coping reaction by American businesses in the 70s and 80s who were afraid of Japanese competition.

But the stereotype does seem to fit some smaller Asian countries a bit better. Singapore, especially, is notorious for having some of the world’s best scientists and engineers, but very few breakthrough discoveries. The same is true of Taiwan. South Korea is somewhere in between — there are a few standout Korean inventions, but so far no science Nobels and few game-changing products. Together those three countries have 80 million people — about 2/3 of Japan’s population — and yet together they’ve produced far fewer breakthroughs than Japan.

The good news here is that a country doesn’t actually have to produce a bunch of standout inventions and Nobel-winning scientific discoveries in order to get rich. Singapore, Korea, and Taiwan all have higher per capita GDP than Japan does. So the question of “Where are all the Chinese breakthroughs?” might ultimately not matter to China’s leaders. Being “giant Korea” or “giant Taiwan” doesn’t sound like a particularly bad fate.

Still, I do wonder why China, with its vast talent pool, its avalanche of research funding, and its huge consumer markets, hasn’t produced more game-changing inventions and discoveries yet. I really doubt it’s a function of autocracy — the CCP would surely reward a Chinese researcher for inventing mRNA vaccines or the transformer model or Crispr. And Frank Wang wasn’t punished for inventing the modern quadcopter drone — in fact, he’s a billionaire, and seems to be escaping the negative attention that peers like Jack Ma have received.

One possibility is that China’s economic institutions reward fast-following and intense competition over breakthrough innovation. The lack of strong intellectual property protection might make it economically pointless to invent something really new — it’ll just get copied by someone else who takes all the money. That seems like it would encourage more incremental advances. In science, incentives for quantity of papers over quality might be the culprit. These incentives, along with various industrial policies, might produce intensive overcompetition, which I believe Chinese people call “neijuan”.

Whether China can tweak its system to produce more breakthrough discoveries and inventions is an open question. Whether it should even care about doing so, given the success of countries like Singapore, Taiwan, and Korea, is another open question. The country certainly does tons of innovation, and maybe the incremental kind is all you really need.

But if the scarcity of breakthroughs persists, I think there’s the possibility that, between that and China’s censorship of art and culture, 21st century great powers might simply turn out to be a bit more boring than their 20th century predecessors.

This article was originally published in Noahpinion and is republished here with permission.