The global agricultural investment spotlight has moved ‘down under’ and is fixed firmly on the Australian dairy farm sector. Long overlooked as the ‘poor cousin’ of the agricultural sector, Australian dairy is now coming of age. Cattle stations, broad-acre cropping properties, wool and lamb-producing grazing properties and permanent row crops like citrus and almond orchards have been the darlings of the investment community as institutional money has flowed into the great southern land. But in recent months the focus is increasingly on the nation’s dairy farms – and for good reasons.

Located on the best arable land, access to huge and growing markets, consistent cash turnover and consistent capital growth that historically produces 6%+ returns, have institutions with their rulers out. The Asian food boom underpins the rising tide that is the Australian dairy sector. Recent market research from Euromonitor International shows that by 2020 China will overtake the United States as the world’s largest dairy market, and more than 60% of all new dairy sales in the next five years are expected to be generated in the Asia Pacific region. All that’s happening right in Australia’s backyard where Australian dairy products are in high demand. Such is the growing demand for agricultural commodities from Asia that farming is now firmly entrenched as Australia’s biggest contributor to the nation’s GDP – and the fastest growing sector with a 23% growth in the 2 year period of 2016 / 17.

Australia exports 50% of its dairy production and it has capacity to increase production to meet demand. Many view an investment in Australian dairy farms as a proxy investment in the Asian food boom – with little of the risk. While China is the largest and most exciting market for Australian dairy, the nation’s processors have extensive footholds in the other booming regional markets including Indonesia, Japan, Thailand, Korea and Vietnam. As these markets grow, demands are being made of Australia to increase supply – and the dairy industry is set to respond.

The industry hangs its hat on an international reputation for being clean, green and ethically produced; proximity to market and competitive pricing through a low cost-base farming system. While the thematic makes sense, getting set in the dairy industry has always had some hurdles. Scale has always been a large dissuader with the average acquisition size, including cows and plant & equipment, between AUD4 – 7million. For institutions looking to place decent bets, that’s simply too small. However there are now an increasing number of aggregations of dairy farms that make the due diligence and ticket size meaningful. Secondly, finding an experienced management team to aggregate and then manage such a portfolio has also been difficult. Dairying is the most demanding of all agricultural industries. Twice-a-day milking every day of the year is gruelling work and experienced management teams have been hard to find. That too is changing. Thirdly, for some years it was a lonely place for institutional investors with only a handful taking the plunge. The opportunity for liquidity was often in question, given a paucity of players in the game with big balance sheets and access to big chequebooks.

Over time that too has slowly changed with up to 20 institutions now actively invested in the sector, including European, Australian and north American pension funds, US endowment funds, Asian SPVs and many family offices. Leading the charge are North American and European pension funds with ‘over-the-horizon’ investment mandates and the patience to ride through the inevitable seasonal fluctuations that are the hallmarks of agricultural investment. Canadian giant PSP Investments has recently acquired 4 farms in Tasmania; US pension fund-backed Laguna Bay Pastoral Company has made a foray into the industry building a portfolio of 10 farms milking 10,000 cows; Thai food group Dutch Mill is another with farms and a factory purchase; Singapore-based Milltrust is also another recent entrant. Existing investors include Australian superannuation giants Telstra Super and Vision Super. The large international institutional investors have for decades watched the value accretion of farmland in the UK, Europe and the better farming states in North America.

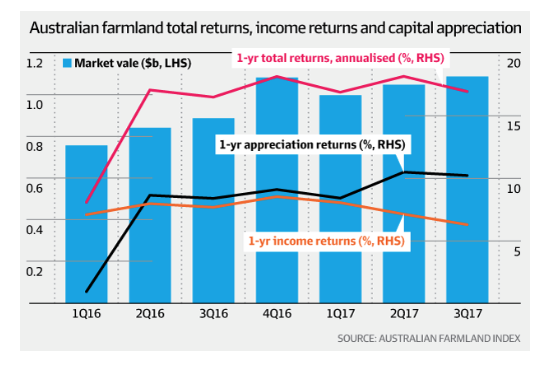

Recent surveys now show that Australia is the investment hotspot with returns from Australia’s top farming properties now almost three times higher than those from comparable farm operations in the United States – according to the latest farmland index compiled by the National Council of Real Estate Investment Fiduciaries. While the third quarter saw a seasonal dip in returns for Australia, the index shows that the total return for the full year to September reached 16.95 per cent, much higher than the 6.15 per cent reported over the same period by the NCREIF US Farmland Index. The high level return was driven by income returns of 6.30 per cent and capital gains of 10.23 per cent.

While this year’s results have been driven by some anomalous events, the 20 year spread on farmland growth by Rural Bank’s Australian Farmland Values index shows a 6% annual capital growth. For those willing to trade the cycle, returns can be very attractive, with farmland in the state of Victoria recording a 16.5% valuation increase in 2016.

Australian dairy land prices are also inexpensive when compared with similar land in Europe, US or even New Zealand – for the moment. For example the best dairy farmland in Australia trades at AUD10,000 per acre (GBP5700pa), while there’s plenty of excellent dairying country available at circa AUD5000 per acre(GBP2850pa). By contrast, in New Zealand the better dairy land is at NZD30,000 per acre (GBP15,900pa).

Many are starting to bet that the value dislocation won’t last and Australian farmland must catch up to those of its competitors. Along the way, an investment is a very secure capital protection play. Dairying is conducted on the best agricultural land with the most secure water resources. Since white settlement, this category of farmland has never retreated in value. Dairy farming has historically been conducted on the edge of the major towns to allow for the convenient transport of fresh milk. Operationally that’s made life easier, but it also means that farmland often has longer term development options.

Land suitable for dairying is also suited to most other intensive farming operations, particularly horticulture. So the Armageddon option for dairy farmers tired of milking, is to sell their herd and grow lettuce or corn. They can make that transition within 3 months. This security is very attractive to the cabal investors with long-term horizons. For international investors, Australia is also a very low risk environment.

It has a stable, democratic Westminster system of government where the two major parties are busy tripping over themselves in the battle for the middle ground – basically putting a different dust jacket around the same policies. Foreign investment is welcome, the currency is stable, there’s ample recourse through a robust and independent legal system that applies the rule of law and absolute freehold title applies. For Europeans and North Americans it really is a ‘home away from home.’

Investors from nations that were once part of the British empire find particular favour with the broader population. The widespread xenophobia that came with the first rush of Chinese investment in Australian agriculture is now tempered – leading to ever-increasing interest from Australian dairy’s largest trading partner. Even recent changes to the rules around foreign investment are of nuisance value rather than a real deterrent.

The caveat to investing in the sector is that any investment in agriculture comes with operational risk. Australia is a sunburnt country and droughts happen, so do floods and fires and global shifts in commodity prices impact in the colonies as they do elsewhere. However due to the micro-management required in dairying, many of these weather-related risks can be somewhat mitigated. Most dairying is conducted on irrigated country, where value-accretive water resources supplement rainfall. In fact water rights have become almost as valuable as the land on which they can be used. Water values have soared by 100% in the past 5 years in some regions, adding millions to the value of many agricultural investments.

There are all sorts of physical and financial instruments that are used to mitigate price fluctuations in key inputs such as water, grain, fodder and fertiliser. There’s another dynamic at play in Australia that is also lighting a fire beneath the dairy industry. The population of dairy farmers is ageing –with the average now at 58 years. Many want to retire but their farms are too small and inefficient and their children simply do not want to farm. These farmers are leaving the industry at the rate of 300 per year – quite a haemorrhage from an industry with only 5800 registered participants. The farmers that remain are buying up the smaller holdings and milking more cows – ostensibly concentrating the means of production in the hands of a few. That too is changing the dynamic between farmers and the processors. Where once farmers were price takers, they’re now increasingly price setters as they use their larger milk supply to argue for higher farm gate prices – and it’s working. This shift in power back to the farmgate will mean sustainable milk prices that will underpin farm profitability, and in turn land values, for decades. Processors need to secure the supply of milk for their growing markets from a diminishing number of farm suppliers. So it stands to reason that the winners will be those holding large portfolios of prime dairy farms in the key dairying regions.