Since China’s economic take-off in 2000, investment has driven GDP whilst the contribution of consumers’ spending diminished. This is common in export-oriented economies, but China’s low private consumption has continued for over a decade, setting it apart.

There are many factors behind this: the uncertainty created by the transition from full-blown communism caused households to save, not spend; To generate rapid growth on its own terms, the Chinese authorities prioritized exports, including urban infrastructure improvements to support hyper-efficient manufacturing; the post-GFC stimulus was, in retrospect much too strong, leading to a wave of over investment.

China is shifting gears for future growth and will become a consumer-led economy in little more than seven years (Figure 1). Inflation-adjusted retail sales increased by 10.5% in 2017, up 50 bps from the previous year. Consumer confidence is near the all-time high. New light-vehicle sales were up 11% in the year to April. We hear a lot about China’s “debt mountain,” less about the growing power of the consumer economy. A number of forces are at work creating this change:

- Policy has changed. The government has long recognized that its initial growth strategy has run its course. Excess investment in production capacity has driven return on capital to low levels. The continued flow of low cost goods from China has irritated its trading partners, particularly the United states. More strategically, China wants the yuan to become a global reserve currency and for that, its capital account needs to be opened and the yuan freely traded. Were the capital account to be opened right now, money would flow out of China because of the high risk and low returns currently on offer in the Chinese economy. The economic model had to change, and it is.

- The Chinese are becoming middle class. This rising middle class is anticipated to comprise 65% of total Chinese households by 2027. With higher education, income and different consumer preferences from previous generations, this population will largely define the new consumer economy, as already reflected in China’s surging food, fashion and auto industries.

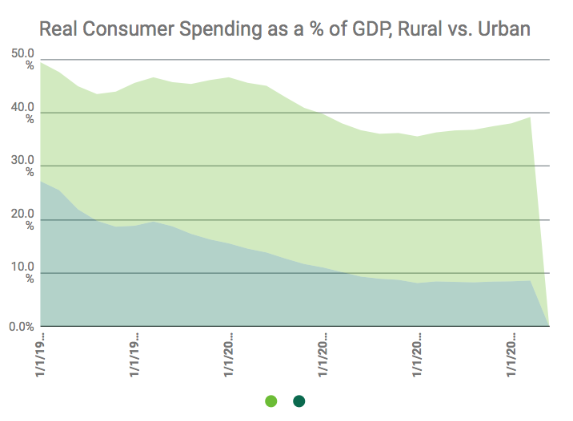

Source: China National Bureau of Statistics & CBRE Research, 2018.

- The internet has unlocked the spending power of rural consumers. Now that urban migration is easing back, the growth of urban real consumer spending started to flatten (Figure 2). However, China’s robust digital economy, which accounts for 30% of current GDP and is expected to make up 35% by 2020, is helping rural consumers to spend more freely, with Internet-enabled mobile devices, convenient digital payments and parcel-based distribution (B2C e-commerce). Since 2012, the real household consumer spending in rural areas rose by 55%, adding up to 9% of GDP. This will only continue as the government’s infrastructure improvements and e-commerce companies’ strategic expansion combine to tap into a larger consumer base.

It won’t be long before China transforms from the world’s factory to the world’s consumer, which is a good thing on many levels. The continual rise of the Chinese consumers points to substantial ongoing demand for logistics facilities in the APAC region. The massive consumer economy in the making is projected to reach $6 trillion by 2020. Its incremental growth over the next three years alone can add another Canada-sized consumer market. Against the backdrop of the U.S.-China trade negotiations, the pace of China’s opening up seems to be accelerating, giving international businesses wider access to Chinese markets and thus phenomenal growth opportunities in many arenas, including real estate and logistics.

Appendix: