When asked by a journalist why she had a mirror above her bed, Mae West answered, ‘to see how I’m doing.’ The same applies to property indices: owners, buyers, lenders and commentators need indices to make sense of what is going on in a market in which almost everyone has some stake. But if you look at indices over the last four years, from when almost everyone agrees the market peaked, you will find a big spread of opinion.

Both Savills and Knight Frank produce indices for London that show a fall in the market of between 16% and 8% respectively since 2014. Over the same period, the Land Registry says it was down 9% in Prime Central London – while for the same areas, Lonres (a firm that aggregates market information) reckon they were down 7%. A big London Estate (a proxy for the market) had a valuation that was 4% up in 2015 and flat in 2016. These are big differences. Does it matter? Well yes; sentiment is a funny thing and often self-fulfilling. Buyers like buying into a rising market and a ‘falling market’ is a good reason to sit on your hands. It also matters in court, getting a mortgage or settling a divorce. These discrepancies in what should be a transparent and sophisticated market shouldn’t happen.

Why do they? Much of it is down to methodology. The main estate agents’ indices use valuation to produce their figures. A basket of flats and houses is assessed by individual offices once a quarter. These indices have less to do with actual sales but a lot to do with how optimistic or pessimistic the valuer is feeling. When turnover is low, and your bonus is dependent on it, it’s easy to conflate turnover and value. Over time this can produce large discrepancies – so much so that one index had to be recalculated as it was wrong by nearly half. On the other hand you have the Land Registry which is compiled on completed sales. Unfortunately it is bald information that, for example, takes no account of lease length or size. It is also a lagging indicator as completions can be months – sometimes years – later. What you are measuring also makes a difference. Take so called Prime? Does it include Nine Elms? Or the Cromwell Road? You can start to see the problems.

So did we at Property Vision – and we now have our own index for Prime Central London – but have set about it in a way that we believe will address the weaknesses outlined above. Perfection is impossible – but as accurate as possible will do. We have a database of market intelligence going back twenty-five years off which our London business is run. We have access to Lonres as a cross-checking tool and we know what we want – to produce information that is up to date, based on real sales in the streets and areas in which our clients would like to buy, that will stand up to forensic scrutiny and, ultimately, be the go-to index for a very specific area – Prime Central London. We have chosen to define this narrowly in post code terms as SW1/3/5/7 and 10, W1/2/8/10/11and 14, NW1/3 and 8 and WC1and 2. After much deliberation, we decided to exclude new developments being sold off-plan as the pricing information we have is not accurate enough; developers, for obvious reasons, prefer opacity to clarity.

Size, location, lease length and condition are the main variables in any property. Size is dealt with by using the price per square foot on exchange of contracts and adjusted for lease length. The house and the flat markets are different so we have split them. As mentioned earlier, we have rejected streets that are second rate in an area that would, as a whole, be considered prime. We have included, for example, Onslow Square but reject the Cromwell Road. We compare properties in the same street but smooth out the data to make a meaningful index that tracks the change in the market. It is a method called Hedonic Regression and used by, amongst others, the Halifax Index.The one factor that is very difficult to compress into an index is condition, but if the sample is large enough, this effect should not be statistically important. If you think about it, the number of houses or flats in really bad condition in Central London is tiny; hardly big enough to influence an average – an average being what we are after.

What does it reveal?

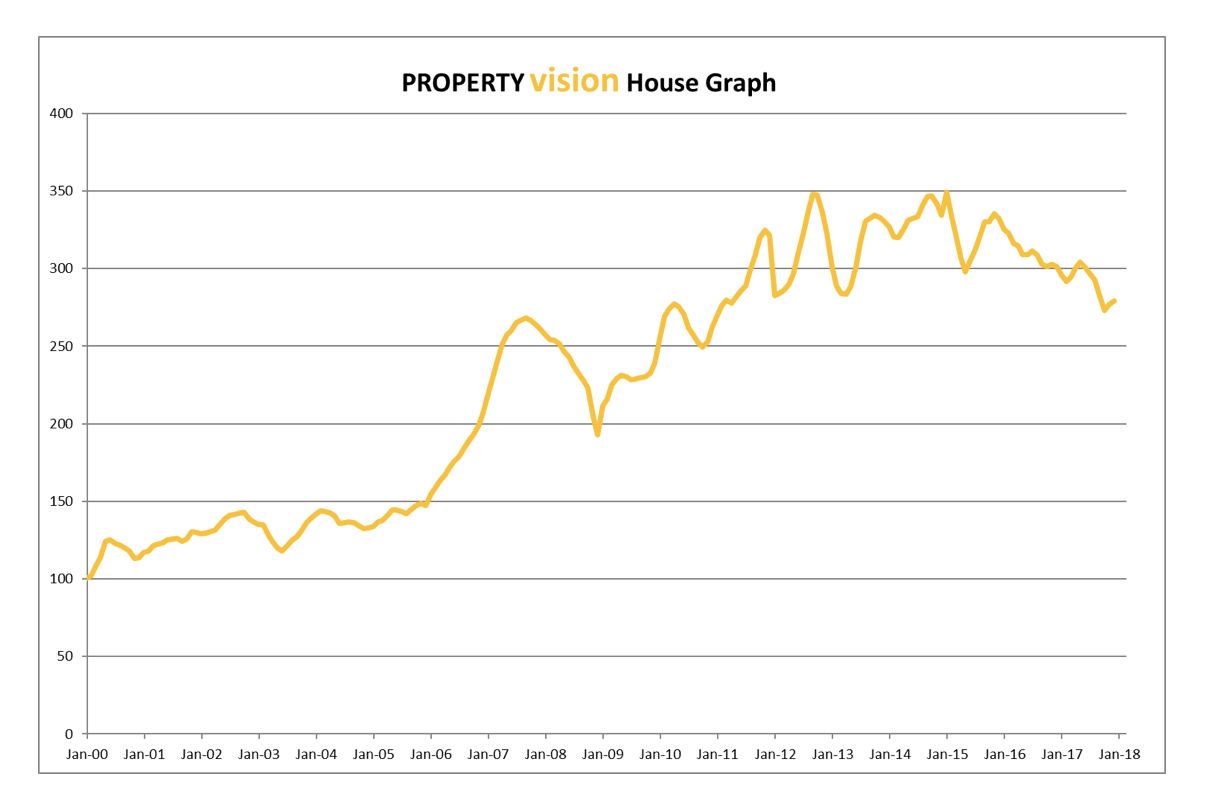

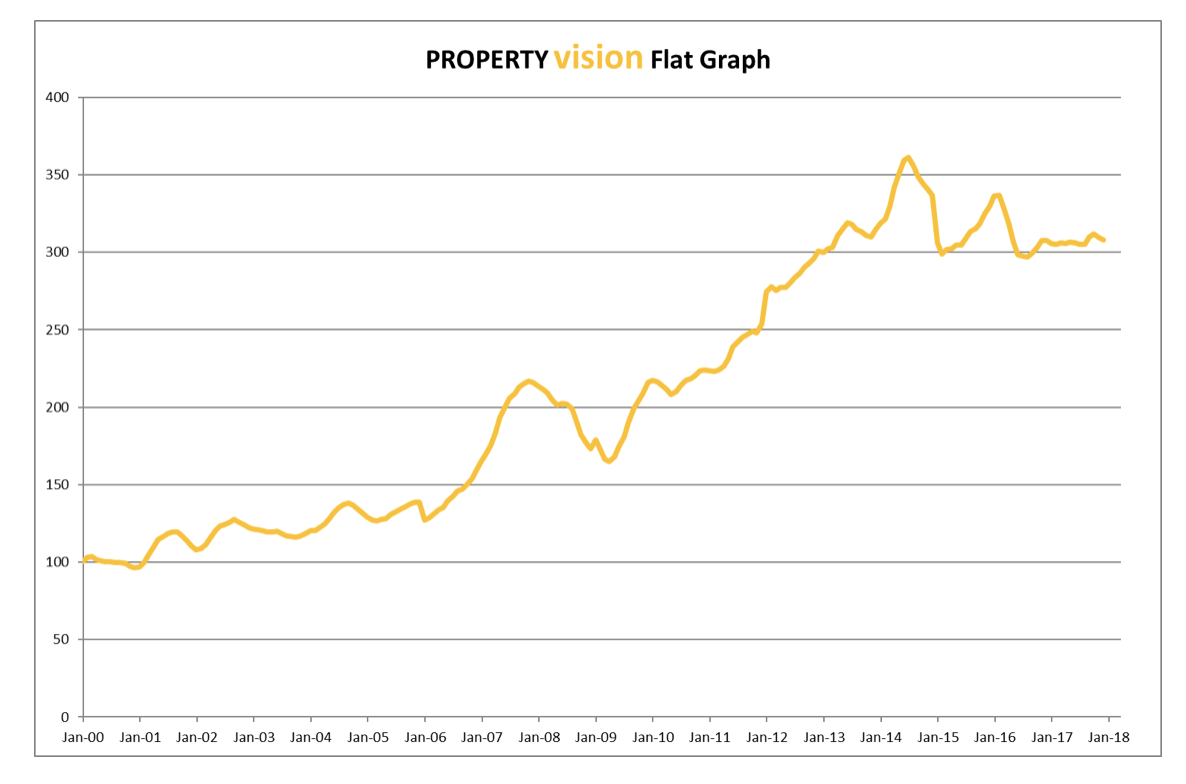

Here are the graphs for houses and flats – more user friendly than raw numbers and better for illustrating trends

Putting this in percentage terms 2017 saw a decline of 7.3% in houses and a plateauing of the flat market. Since the market peak of 2014, houses are off 20.7% and flats down by 14.7% – which demonstrates the efficacy of splitting the two. Houses are now below 2007 in real terms..

What it shows is not pretty – and shows what you can do, as Chancellor, if you throw enough sand into the gear box. Unfortunately the current, politically weak, Chancellor decided in his last budget not to apply any oil. Despite that, the market is definitely looking and feeling better this year – but that, as ever, depends on quality: wide, modern, air conditioned flats are going at a premium and tall, tired houses at a discount. In the large scale new-build market – the towers that are erupting all over the South Bank – there is an obvious oversupply and prices must be off by considerably more than in Prime Central London; but that is another story.