Britain in 2025 will be very different from today. London and the UK reached peak inequality in 2018. That was when income inequalities at the very top were first seen to fall. We are past the peak of income inequality today. House prices have been falling in London since August 2016. They fell first and hardest in the more affluent parts of London. Salaries near the top in London have stalled. For the highest paid chief executive officers who live in the capital, they have fallen by around a million pounds per man (they have fallen a little less for the few women in such posts, but this is only because gender inequality at the top is declining).

In April 2018, the European Banking Authority revealed that there had been a 10% drop in the number of bankers in Europe being paid a million Euros in 2016 alone (from 5,142 in 2015 to 4,597 in 2016). Almost all of this was income lost by bankers working in London, as almost all of these bankers lived and worked in the capital. The pound had fallen; but more importantly it was almost exclusively the London banks that began paying their ‘top talent’ less.

By 2016, even before the vote for Brexit could have had any effect, London had past peak banker pay. And since 2016, it has slumped further. After all, you don’t pay somebody more in London when you are trying to persuade them to relocate to Dublin, Frankfurt or Paris.

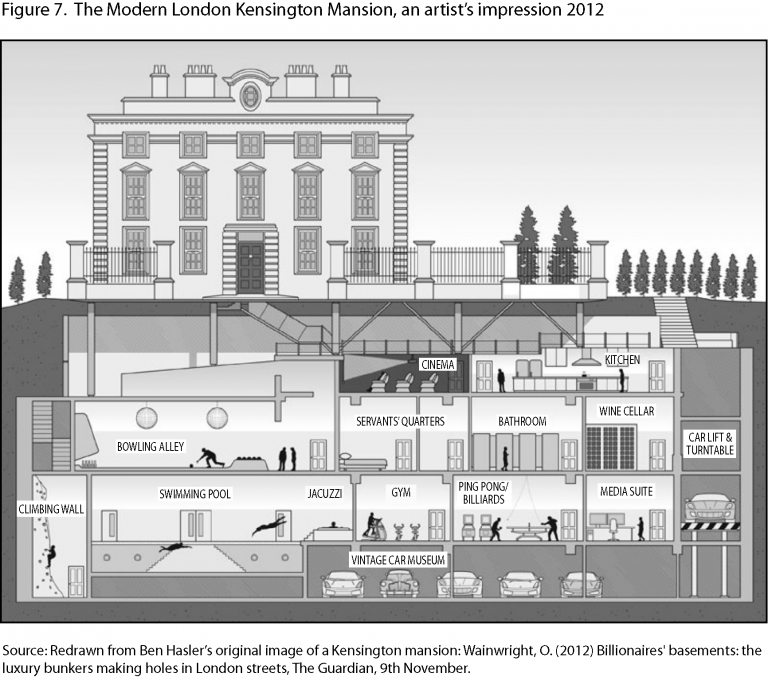

Figure 7 from “All that is Solid: The Great Housing Disaster (Penguin, 2014)

If you are a London-based architect and you were wondering why the commissions were a little thin on the ground, it is because there is less money out there than there was, and far greater uncertainty. Falling house prices is another reason why fewer people might ask you to come and redesign their ground floor and bedrooms, knock all the walls out here and put an extra basement room in there. Suddenly they start to worry about the equity. Suddenly it’s not play-money anymore. Suddenly that kitchen can last a few more years. The conservatory can wait. Let’s not buy up those two flats and knock them into one – not quite yet.

The effect of economic changes on London housing has been witnessed through history. London’s housing today mostly reflects the tribute received at the heart of the world’s largest empire. Tribute that allowed the first great underground train system to be built and metro land to expand. But as the Empire waned, and was then lost, London’s housing changed. The last time London hit a peak of income inequality was in 1913. Back then, monied families would arrive in the capital with their servants for the season. Servants lived in the basements and attics of the grand houses and the families lived in the middle floors.

Then everything changed. It was not just the First World War, or the Russian Revolution, or the agitation of trade unionist, or the rent strikes, or the women who won the vote, or the general strike, or the economic crash, or the depression – it was everything. Soon the most common job for women in England ceased to be a servant. In fact, within just a few decades there were almost no servants. And almost no gentry.

In turn London housing was transformed. By the 1960s and 1970s many – if not most – of the grand houses had been subdivided into flats to house several separate households. New housing was being built for families to be allocated on the basis of their need rather than ability to pay. Most of London’s social housing came late to the capital in comparison to the rest of England. By the end of the 1970s, housing across England was distributed as fairly as it had ever been. There was the least overcrowding and the least underuse of property. When income equality was at its highest across the UK we had the fewest unused bedrooms and the least empty property in the capital.

But then people forgot what they had won, and inequality began to rise again. During the affluent 1980s, social housing began to be sold off to tenants who, in turn, sold it on to new private landlords. Suddenly, a maisonette that had been a home to a happy family of four became the rented living space for a disgruntled single ‘professional’. Inefficiency in the use of housing increased greatly when the market was allowed to let rip. By the time of the 2008 crash, the flats had often been knocked though, and the grand houses restored, although more often than not for someone who flew in from Qatar or Moscow for the season – with their servants.

Figure 1 from “All that is Solid: The Great Housing Disaster (Penguin, 2014)

Now, the UK government is running out of money and history risks repeating itself, but never quite as before. In the past, it was through introducing very high income tax that the government found the monies it needed in the 1920s and 1930s as inequalities then fell. Today there will need to be new taxes, as more money is locked up in wealth than income. Property taxation is the most obvious way to tap the wealth. Council tax levies across London will one day soon be equalized, so you no longer pay the least if you live in the poshest of boroughs, and the council tax and will be extended up to band Z.

Empty homes will be double or triple taxed. Tenants will be given rights – three-year tenancies says the current (Conservative) government. This is a good first step, if they actually implement it, but it is only the first step along a very long road towards greater equality and the UK becoming a normal European country. In normal European countries private tenants have far better rights than in the UK and housing cannot be used be so many speculators. All those people who brought property in the capital thinking it is a safety deposit box for their money are about to get a rude shock.

The 1960s and 1970s were a time of young families, whereas the future, more equitable London will be a London of older people and more people living on their own. That future London is today’s Tokyo or Stockholm. London’s mansion blocks will morph accordingly. They will be divided into smaller, more affordable spaces that can be owned by a more equal society in London. They will be rented out at fair renst and the quality will have to be high – not awful as is so often the case today. This raises all sorts of questions as to how architecturally London housing can be adapted.

How do you fit all the doors that are needed onto the front of the former London mansion block, to accommodate entrances to the sub-divided spaces? How do you connect them to the lifts that will be required to take people with old hips to their carved out, comfortable, liveable pocket of what was once wasteful decadence? And what do you do with all those subterranean basements built many floors beneath the city now? Collectively they are the height of hundreds of Grenfell towers. While we have been failing to build new social housing for those in most need, the richest have been adding huge home cinemas and swimming pools beneath the ground. How can they be adapted to turn them into part of a real home?

Grenfell Tower, Autumn 2017

We are at the very start of what is a very positive change. We are beginning to leave a time of madness when simply owning property earnt someone more than working in a year. We are realising that the market is the most inefficient way of allocating housing. Letting the market rip leaves thousands sleeping rough on the streets and millions living in dwelling unfit for human habitation. If you want a challenge to think about take a look at Bishops Avenue, just to the north of Hampstead Heath. Take the time to walk along that road one weekend and think – what would be the best use of this space in London in the future?

Originally published on dannydorling.org