I keep hearing it said that we should not re-regulate private renting, or if we do then we need to be very careful about it, lest landlords disinvest. This would exacerbate supply issues in places like London, it is claimed. One policy type told me last week that restricting what landlords can do with their properties had ‘implications for supply… we already have a shortage here!’ Sadiq Khan’s interest in rent stabilisation measures (presumably via some kind of index-linking) risks ‘the loss of good landlords’, the National Landlords Association warned. The government, meanwhile, is said to be treading very warily around the issue of security of tenure for fear that it will deter landlord investment.

To the extent that additional burdens would put off investment in new-build developments, there is a valid point to consider here. But new-build by landlords is tiny relative to the size of the sector, the vast majority of which comprises stock that was previously owner-occupied, and much of it council-owned before that. Only about 10 per cent of the 4.4m homes that are privately rented were even built post-2002; more than a third are pre-World War One. So the idea that landlords contribute to the supply of housing is mostly false. Landlords have invested in existing homes while interest rates and the returns on competing assets have been low. In so doing they have edged out of the market perhaps in the region of 2.5 million households who otherwise would have bought a home by now. Those households now rent from the landlords who edged them out.

Depending on your view of these matters, this is not necessarily a problem. Owning your own home is one investment option among many, it isn’t necessarily as good a deal as many tend to assume (as Ian Mulheirn has expertly explained), and the headlong pursuit of mass owner-occupation has not all been plain sailing in the macroeconomic context. But where it is certainly a problem is if standards in the private rented sector fall significantly below those that owner-occupiers enjoy, so that those who cannot (or choose not to) buy a home live in second-class accommodation. This is where regulation is important, and as Christine Whitehead and Peter Williams pointed out in a recent study of international comparisons, the UK ‘probably sits at one extreme’ in this regard. The deregulated extreme, that is.

The precise nature of such regulation can be debated, and unintended consequences are always an important consideration, but it makes little sense to run scared of landlord disinvestment unless your overriding objective is to maintain the size of the private rented sector – or even increase it – at the expense of would-be first-time buyers. If a landlord sells a property, it does not disappear into thin air. For a home to leave the private rented sector there has to be a corresponding buyer who is going to live in it, meaning it will then be classed as owner-occupied. The size of the housing stock does not change, only the tenure split of that stock alters.

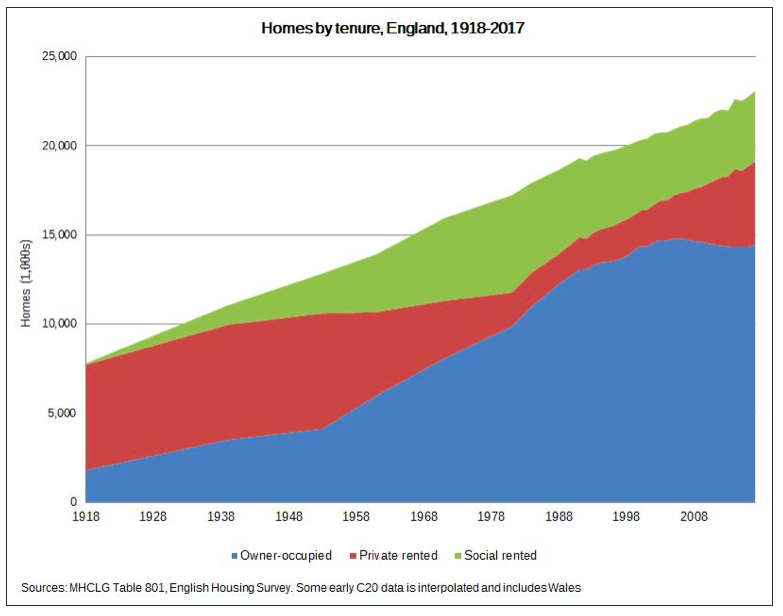

We can get a sense of this by looking at the housing stock of England between 1918 and 2017 in the chart above. During that time the number of homes has increased from about 8m to about 23m. Within that stock there have been very large shifts in the tenure split. The biggest is the collapse in the number of private rented homes between 1918 and the early 1980s. During this time the private rented sector was heavily regulated, notably by hard rent controls for most of the period, which encouraged landlords to disinvest. But those homes (at least those that weren’t demolished in slum clearance) were steadily purchased by homeowners, as were new-build homes, and the size of the owner-occupied sector ballooned alongside. What we have seen since the late 1990s is that process go into reverse, as private renting has been deregulated (rent controls and security of tenure abolished at the tail end of the Thatcher government), interest rates have fallen and mortgage availability for landlords stepped by the banks.

So the balance between the tenures – who owns the homes that were there already and will be there in any event – is not particularly significant for supply. There are a few caveats though. The first, mentioned already, is that when landlords are investing in new-build, they are contributing to supply. Uppermost here is the institutional investment in build-to-rent which has finally begun to take off in recent years. It would not be helpful if steps to re-regulate choke off that investment, particularly given that it is the part of the private rented sector that possibly least needs additional regulation: it is mostly targeted at the more affluent, who have a better chance to vote with their feet, and anecdotally I detect that the ‘offer’ to new tenants, including longer tenancies, is often superior to that in the traditional private rented sector. For that reason it might be sensible to carve out exemptions for new-build (perhaps for a period of 20 or 30 years), as is customary in countries that have higher levels of regulation.

A second caveat may be that, while a tenure shift does not materially affect supply, might it affect demand? There is no clear data on this but I believe, for instance, that household formation has fallen slightly over the past 20 years as a result of younger people finding it more difficult to buy a home. Faced with the choice between renting or continuing to live with their parents, some (not all) who would otherwise have bought their first home have decided to remain with their parents a bit longer. To the extent this is the case, if owner-occupation became more accessible we would expect that to go into reverse. This means that while the supply of homes would not change, there might be some shift in the demand for them. This is likely to be only a very small adjustment in the scheme of things, however, on the very margins of this question. And to the extent that we need more homes, then we need to build them: relying on depressed household formation due to the size of the private rented sector is not much of a strategy.

Finally, housing stock is much more efficiently consumed in the private rented sector than in owner-occupation. Fifty per cent of owner-occupied homes – half! – are under-occupied, according to the English Housing Survey, compared with just eight per cent of those in the private rented sector. What if, then, a landlord sells a home that has been occupied by eight people to an owner-occupier who wants it to live in with just their partner and two children? Or even just on their own? Superficially this might look like a case where the property would more usefully be kept in the private rented sector, where a landlord is more minded to sub-divide to collect more rent. But over-consumption is a demand issue, not a supply one, that also predates the tenure shift. A more efficient use of the housing space we have would be desirable but that must surely begin by tackling the tendency to under-occupy across that entire half of the owner-occupied sector, not by fixating on the comparatively small number of homes that cross into it from the private rented sector. The answers to that probably lie in taxing property more progressively and addressing some of the hidden subsidies that owner-occupies enjoy and which reinforce the under-occupation.

None of these side-issues make a fundamental difference to the basic fact that shifts in housing tenure are quite different to shifts in housing supply. If we are designing policy to support the continued expansion of the private rented sector at the expense of would-be first-time buyers, then re-regulating renting might indeed be a problem: the sector is after all attractive in part due to the almost total freedom landlords have to evict a tenant. That is the story of the past two decades. But if our objective is to improve standards, let’s do what is necessary, relax and let the tenure balance re-adjust as it will.

Article originally published by Civitas.