More likely those yield falls are just

US political adviser James Carville is reputed to have said: “I used to think that, if there was reincarnation, I wanted to come back as the US president or the pope or a .400 baseball hitter. But now I would like to come back as the bond market. You can intimidate everybody.” Government bond markets in the US and Europe have been pretty intimidating lately, with sharp falls in yields suggestive of imminent global economic recession and disinflation. Is the bond market right? Is the global economy falling apart? Is inflation dead? Or has the bond market embarked on a flight of fancy, chasing butterflies into the long grass?

At Economic Perspectives our research indicates that credit markets, rather than bond markets, do the best

job of warning what lies around the corner. As long as the real growth rate of global private and public sector debt is expanding and US corporate credit spreads

are not widening, then the strong likelihood is that the global economy will be growing too. If weighted-average government yield curves are becoming steeper, then more’s the good. If they are flattening or inverting, then this will detract from the real outlook.

Our latest assessment of the credit data shows a stable growth rate of private and public debt, in real terms, of around 3% a year: in advanced economies it’s nearer to 2%, and in emerging economies it’s about 7%. US credit quality spreads spiked in the final quarter of 2018 and have not fully retraced but remain very tight from a longer-term perspective. Government bond yields have inverted in the US and Australia, flattened in Japan, the Eurozone, Russia and Brazil, but steepened in China and India. Overall, this gives a pretty neutral outlook for the global economy, with a bias towards deceleration but not recession.

Does the bond market have a better understanding of the unfolding dynamics of the global economy? One that is distinctly more downbeat and scarily imminent? Or is this all about the market’s confident anticipation that policy-makers will cave in, taking interest rates back to the lower bound and restarting quantitative easing programmes?

In other words, is this ultimately about the capture of the central banks by financial markets?

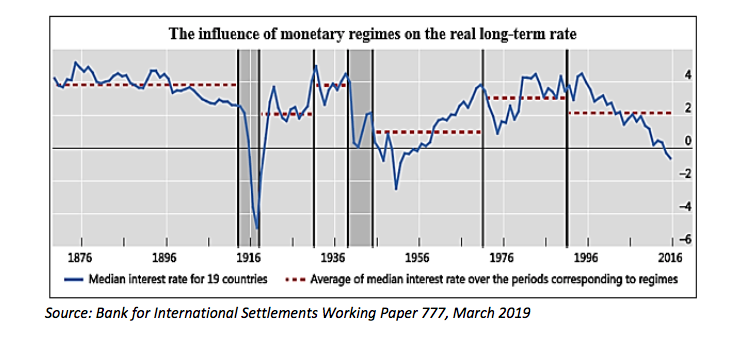

I fear the latter. Not only have the US Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank surrendered their operational independence to the market’s whims, but their ability to stimulate private-sector spending – consumption and investment – is highly questionable. What the central banks may see as pre-emptive easing, analogous to taking out insurance against an economic slowdown, comes across as another act of desperation. The economic case for the July US Fed funds rate cut is threadbare: underlying consumer activity is still expanding, labour market indicators suggest acute supply contraints, underlying inflation trends are little changed from a year ago and financial market conditions are buoyant. Even the money supply is accelerating, propelled by commercial bank purchases of US Treasuries (see figure 1).

The backstory concerns the declining credibility and influence of Fed chair Jay Powell since the autumn of 2018. In the ascendancy is Richard Clarida, installed as vice-chair in September last year. In partnership with New York Fed head John Williams, Clarida has been hard at work to reinstate the Bernanke-Yellen analytical framework as the basis for the communication of Fed monetary policy after Jay Powell sought to distance himself from it.

Speaking in Helsinki in early July, Clarida raised a flag for the elusive concept of ‘r-star’ – the neutral (or natural) real interest rate. “This (alleged) global decline in r-star

is widely expected to persist for years. The decline in neutral policy rates likely reflects several factors, including aging populations, changes in risk-taking behaviour and a slowdown in technology growth,” he said. The repetition of this assertion marks the clearest signal to date that the Fed is preparing to hunker down on interest rates, irrespective of incoming economic data.

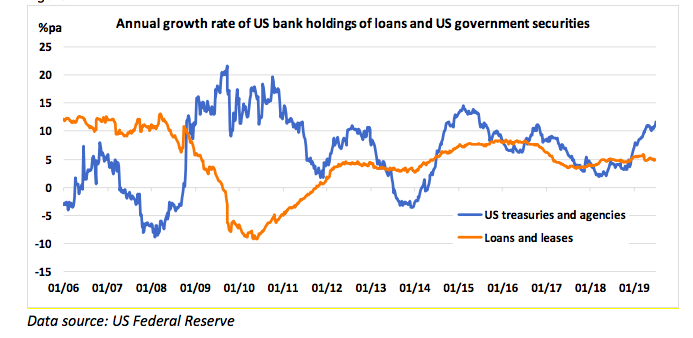

In our experience, the more attached an economist is to a structural explanation, the less likely they are to embark on a cyclical normalisation of interest rates. Claudio Borio of the Bank for International Settlements will hear none of it. In a working paper entitled ‘What Anchors for the Natural Rate of Interest?’, published in March, he and his colleagues provide compelling evidence that “monetary policy plays a significant role in anchoring the financial cycle” (see figure 2). They add: “The reaction function of central banks influences the financial cycle, not least by influencing risk-taking. The cumulative impact of policy today may end up constraining policy choices tomorrow.

“In practical terms, the issue is not so much whether monetary policy should lean against the wind; rather, monetary policy is the wind – for better or worse, the policy regime is a determinant of long-run outcomes (including r-star).” The endogeneity of monetary policy makes the quest to reflect a notional decline in r-star in policy rates a futile and perilous endeavour. What Clarida and Williams are devising is a wartime strategy that will ultimately backfire. Enjoy the era of cheap borrowing while it lasts, but beware the backlash when renewed policy stimulus fails to deliver the hoped-for reflation.

Figure 1

Figure 2