It’s hard to know if debt refinancing at today’s rates is a gross distortion of reality or the shape of things to come

Are interest rate cycles a thing of the past? Have we entered an age of permanently cheap capital? It is astonishing to be asking these questions, but these are extraordinary times. For construction and real estate developers – and investors – it would be helpful to know whether low borrowing rates are a cruel fantasy with imminent expiry or something closer to a settled equilibrium. Is debt refinancing at today’s rates a gross distortion of reality or the shape of things to come?

There are at least three versions of the thesis that we are living in an age of low interest rates. The first is the ‘ice age’ thesis, long expounded by Albert Edwards, the ultra- bearish global strategist at French bank Société Générale. He has argued for many years now that the world is rushing inexorably into a financial ice age, with the developed world following Japan into an era of collapsing bond yields and equity prices. He predicted back in January that yields on US government debt would slide below zero during the next recession. Central bankers are cast as hapless bystanders in this scenario.

The second version is the ‘collapsed roof’ thesis: that interest rates cannot increase because the global debt burden would become intolerable. Interest rates can move only in a very tight, low, range because debt-income ratios are so high. The inference here is that central banks have engaged in financial repression, seeking to prevent an increase in interest rates to an extent that would likely plunge the world economy into recession or depression. This leaves two big questions: do central banks genuinely set interest rates, and how likely is it that they will avoid policy mistakes?

The third version is the idea that central banks have led us towards a socialist utopia, which embraces the radical notion that governments should not have to pay interest on any of their borrowings. This thesis has revived in the context of the popularity of modern monetary theory. Wealth-holders (including pension funds) should be content to hold government bonds solely for their utility as liquid (readily tradable) assets. Therefore governments should borrow freely in order to provide job guarantees, renew the infrastructure, protect the environment and keep everyone safe. That line item for debt service would be so much better deployed elsewhere.

The ice age thesis asserts that the journey towards deflation and negative interest rates is an incomplete adjustment to a new, if unstable equilibrium. The collapsed roof thesis asserts that the new equilibrium is already here and central banks are constrained by it. The socialist utopia thesis is that the existing policy framework is fundamentally flawed and should be abandoned in favour of a new and better equilibrium. What these three theses have in common is a failure to acknowledge that there is an external corrective force, whether of mean reversion or of broader normalisation, which will bring the reign of very low nominal interest rates to an end.

There are two powerful corrective forces that threaten to overturn the era of low inflation and low nominal interest rates. At Economic Perspectives we have showcased each of them in recent seminars: Blowing up the Box on 26 June, and The Coming Collapse of Corporate Credit on 10 October.

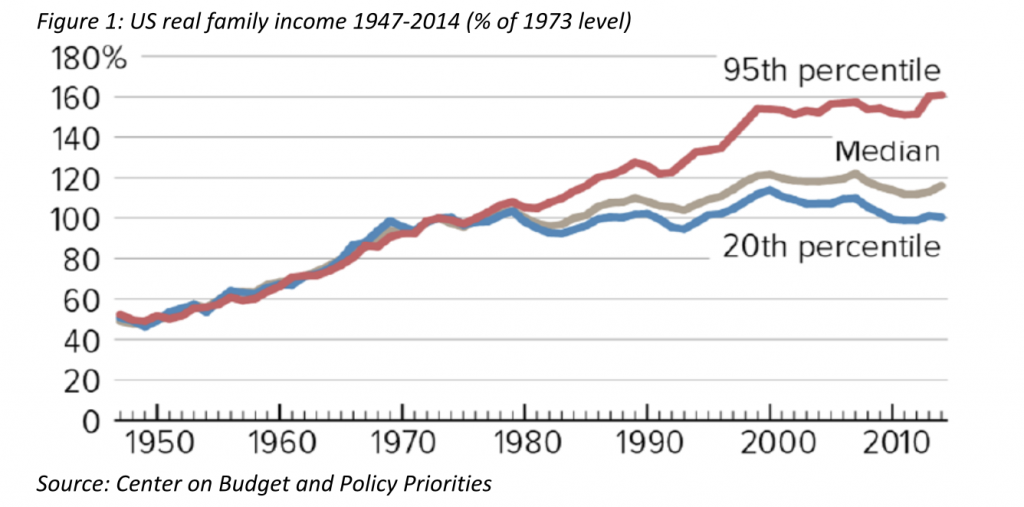

‘Blowing up the box’ refers to the obsolescence of the macro policy framework, or box, that has prevailed in advanced western economies for the past 35 years. This box, designed to lock in low inflation, uphold fiscal discipline and rebuff political interference, is now in mortal danger, charged with inadvertently crystallising and compounding relative economic advantage and disadvantage over the past decade (see figure 1). We stand at the threshold of a policy revolution that will blow up the box, overriding the primacy of the inflation objective and abandoning fiscal orthodoxy into the bargain.

As political economy overrides the ‘new normal’, the policy box is set to explode, bringing a reordering of policy priorities. Central banks will probably be reassigned to the defence of sovereign credit in the context of ambitious public spending programmes and the continued repression of nominal interest rates. In practice, the inflation objective will be jettisoned, and the inflation rate will find a new level, paving the way to significantly higher nominal borrowing costs.

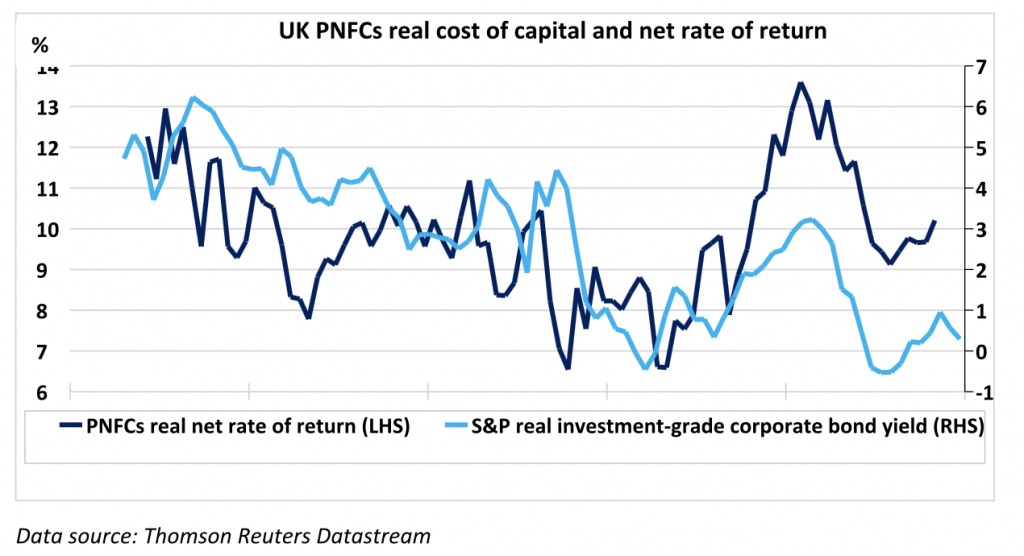

The second threat arises from the unavoidable connection between the cost of private sector borrowing and the return on capital, illustrated for UK non-financial companies in figure 2. A side effect of financial repression is the compression of the net rate of profitability as capital discipline is eroded. The downturn in global corporate profitability and net cash generation is well under way and is intersecting with a skewed distribution of indebtedness: the pricing of corporate credit – in the US, but not only in the US – is bifurcating. The debt issued by a cluster of impressive companies will continue to price off – and sometimes under – their respective government yield curves. But the debt of a fat tail of vulnerable, poorly rated, corporate borrowers will price according to idiosyncratic risk and illiquidity. We observe this effect most clearly in CCC-rated corporate bonds, but our expectation is that the infection will spread up the debt structure, with casualties as highly rated as BBB. Widening credit spreads will signal the end of the global economic expansion, with aggravated impacts on capital spending and employment over the next two to three years.

Central bank financial repression – expressed until now as the suppression of nominal interest rates, the elimination of the term premium and the compression of corporate credit spreads – appears to be losing its grip on the pricing of the weakest credits. We expect that central bank responses, cuts in short-term rates or the resumption of quantitative easing (QE) will be unable to prevent this bifurcation in the pricing of corporate credit.

To summarise, the reign of low nominal interest rates is under siege from a prospective macro policy revolution that up-ends priorities and opens the inflationary valve. The era of low corporate borrowing costs is additionally vulnerable to a fracture in the pricing structure for private sector credit, leaving a significant segment of the market with elevated borrowing costs as a new bond and loan default cycle unfolds.

Figure 2: Cost of borrowing and return on capital, for UK non-financial companies