Several shocks, both positive and negative, have prevented the US economy entering an overdue recessionary phase

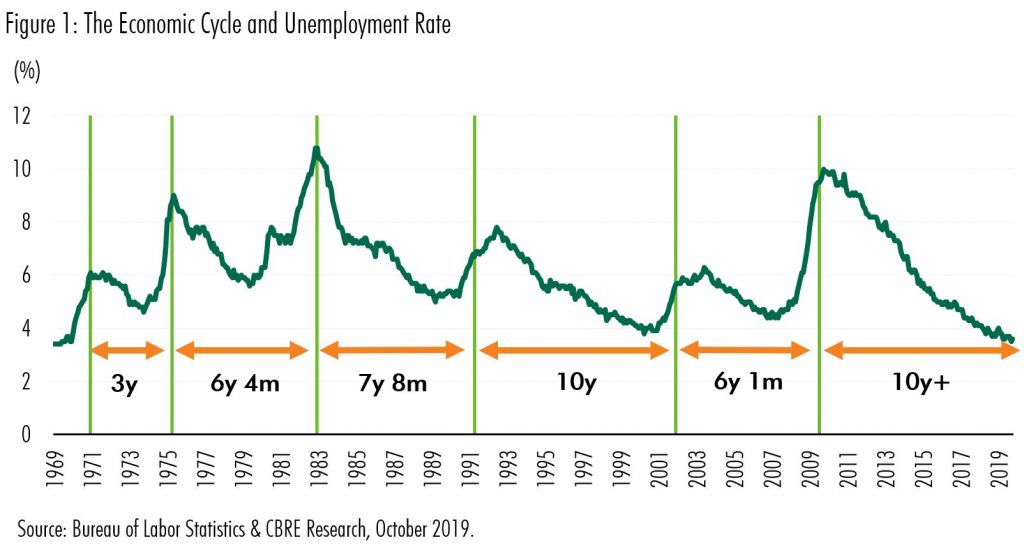

The US economy is in its longest economic expansion on record. The unemployment rate fell to a 50-year low of 3.5% in September (see figure 1). Unemployment is a good way of observing the economic cycle. It does not correlate exactly with economic growth, but it gives a good picture of demand conditions and it reflects most people’s perception of the state of the economy (it is closely related to the real estate vacancy rates, for instance). To understand why this latest cycle has been so long in the US, we need a theory of why recessions happen.

Typically, after a period of sustained above-trend economic growth, aggregate demand catches up with aggregate supply and inflation begins to rise. Interest rates move up to control prices, but often not quickly enough because poor economic data create policy lags. Explosive late-cycle growth sets in, mainly due to over-aggressive lending by banks and often in response to buoyant real estate conditions or high rates of new business creation. Inflation rises sharply and interest rates must play a quick game of catch-up. Economic activity slows and a realisation occurs in the banking business or household sectors that debts cannot be repaid as planned. A recession ensues.

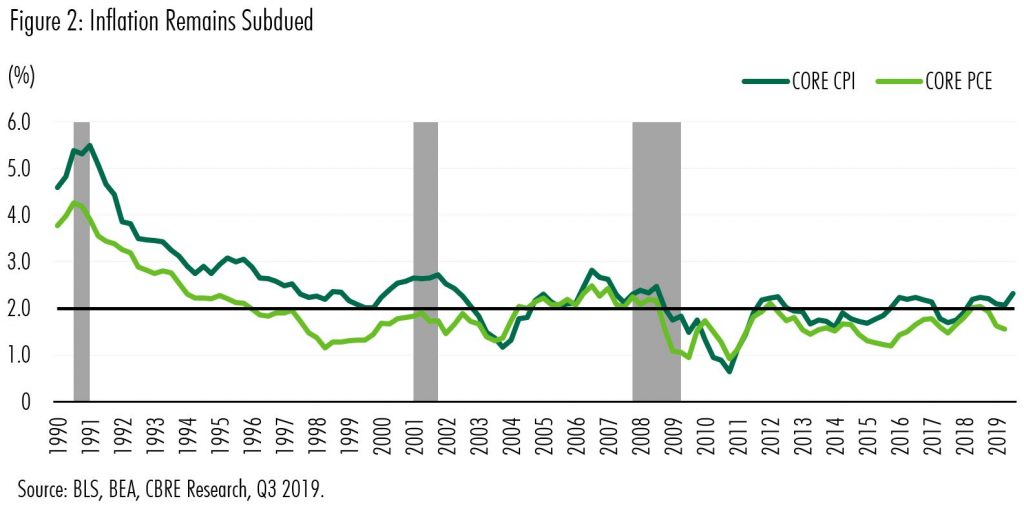

So why hasn’t it happened this time? The answer lies in low inflation and a sustained period of below-trend growth. In the US, three negative demand shocks and two positive supply shocks have created a slow but sustainable economic expansion, in which inflation has not shown up.

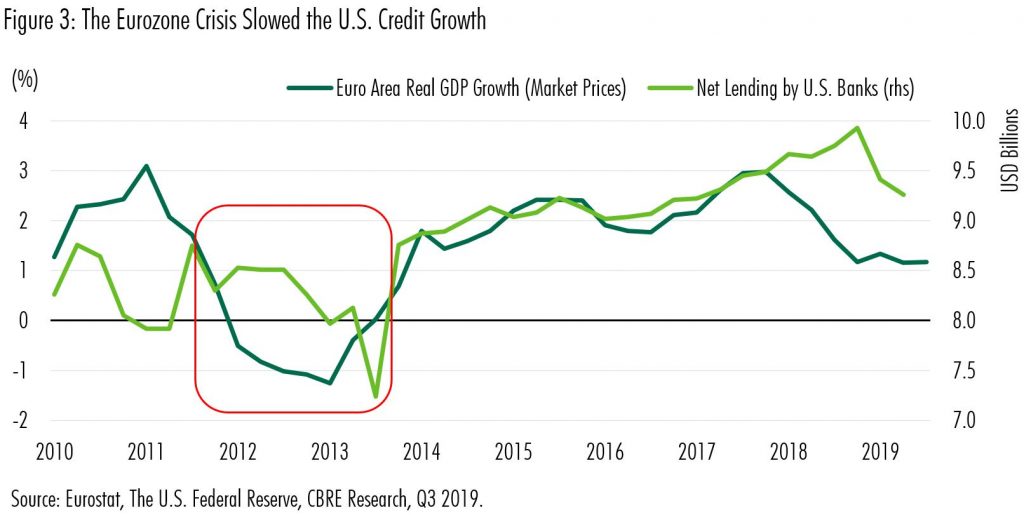

The first of the three negative demand shocks was the eurozone crisis of 2011-12. Following a brief recovery from the Great Recession, the eurozone economy entered a multi- year downturn as several members looked likely to default on sovereign debt obligations. Inflation dipped below 1%.Consumer and business confidence dropped in the US and the softness affected US exports in 2012 and 2013. It also weighed on the US stock market and bank lending (see figure 3).

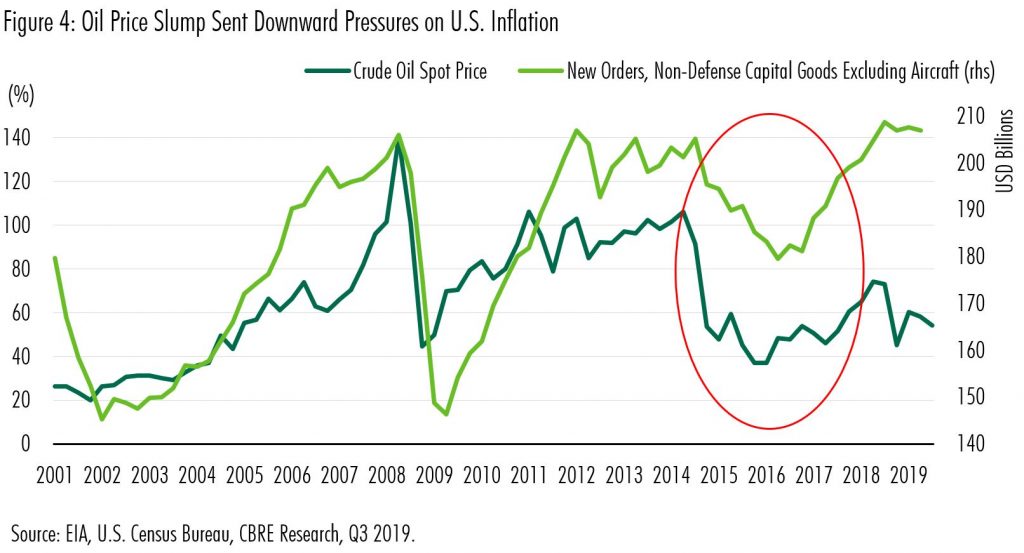

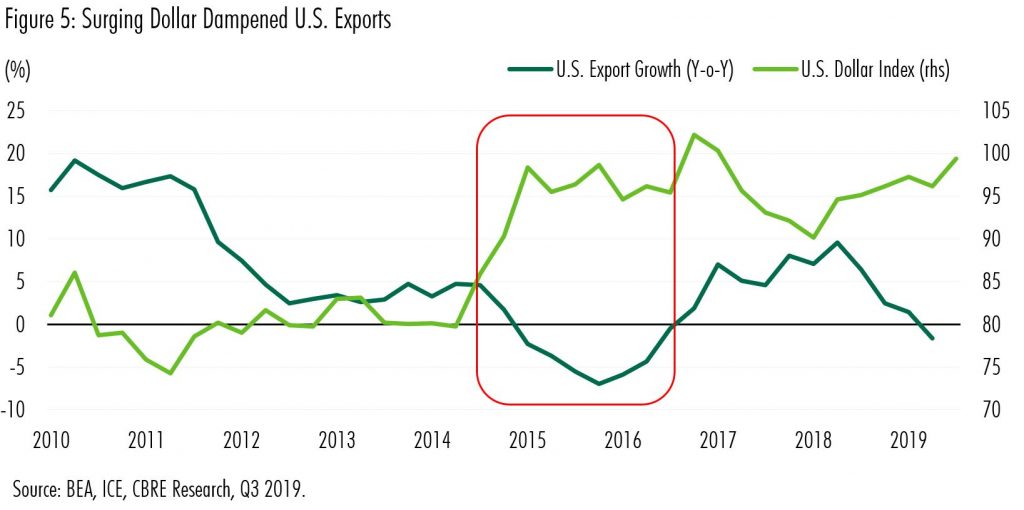

Next came the 2015-16 oil price slump and US dollar surge. The growth of US oil and gas production is a very big deal for the global economy. In the early stages (2010-14), it created a surge in capital expenditures that helped drive US economic recovery. However, when oil prices slumped in 2014 due to a global build-up of supply, some very negative consequences set in for the US economy (see figure 4). The dollar surged (there is an inverse relationship between the price of oil and the value of the dollar), causing exports and capital expenditures to decline. A very weak period of GDP growth ensued, and the US came close to recession (see figure 5).

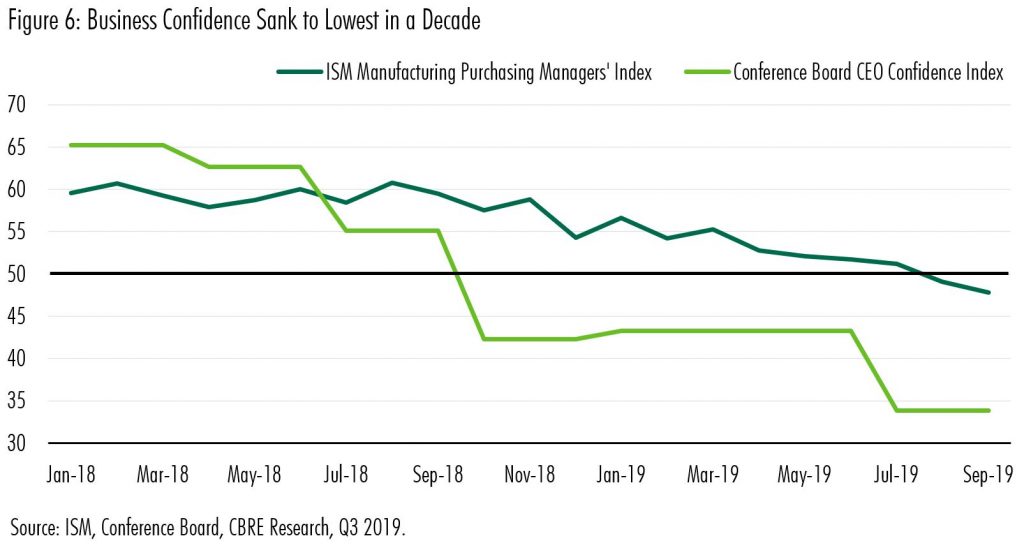

The third negative shock was the trade war and manufacturing recession of 2018. A decline in corporate confidence due to the US-China trade war and the possibility of a hard Brexit has clearly lessened capital expenditures and manufacturing output. The rise of populism has had negative consequences for the economy and potentially the fortunesof the average citizen. However, it is not the only factor at play. An as yet poorly explained downturn in the global auto industry is also at work, as are the ongoing difficulties at Boeing in the wake of the 737 Max debacle.

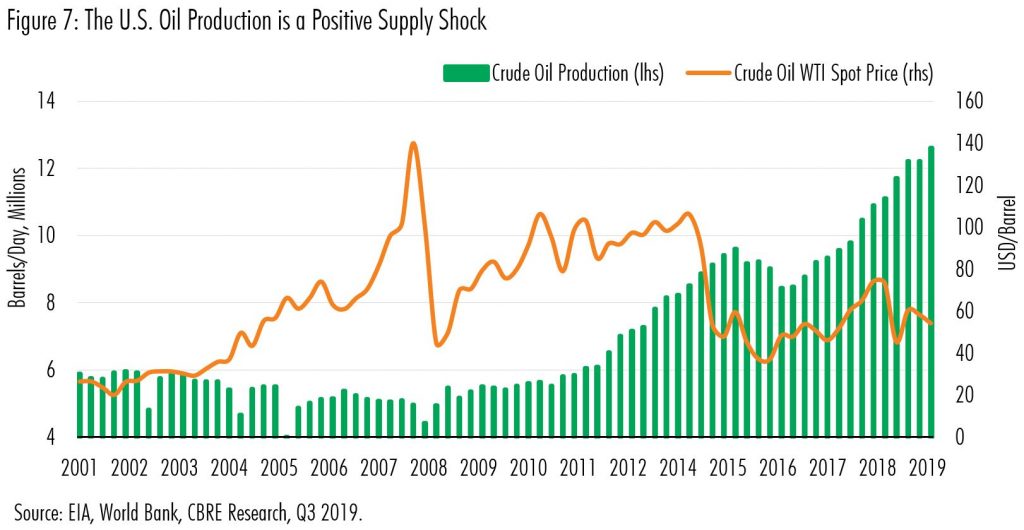

Two positive supply shocks have also contributed to low inflation. The first is the doubling of US oil production since 2012, thanks to new technologies and the absence of production limits. In 2018 the US outproduced Saudi Arabia to become the world’s largest producer of petroleum, and in October 2019 it became a net exporter. The oversupply in the industry has put a cap on oil prices (see figure 7). This is a positive supply-side shock of major proportions, allowing non-inflationary output growth to continue for longer than at any time since the 1970s.

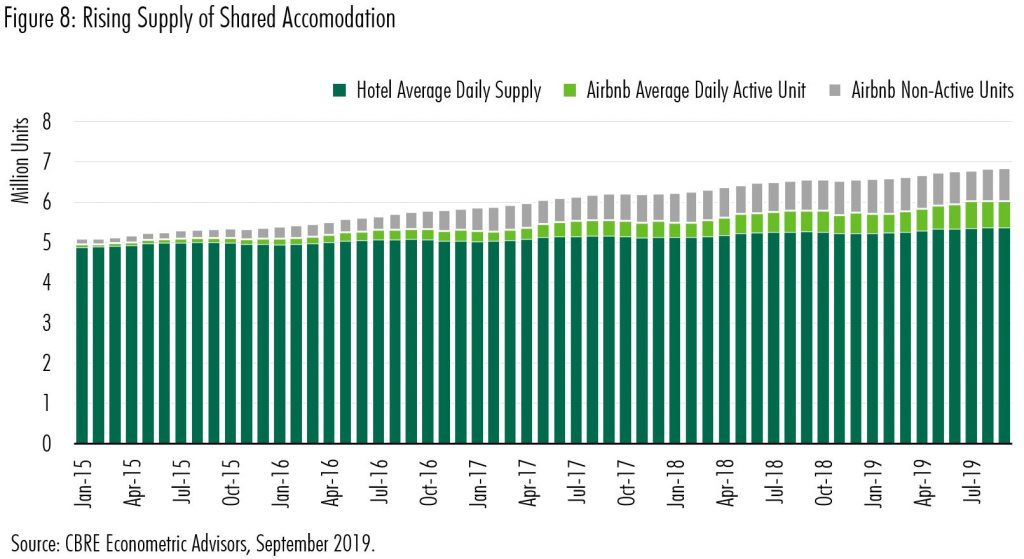

The second positive shock is the rise of the sharing economy since 2009. Led by millennials and Generation Z and facilitated by technology, consumers have developed a penchant for sharing cars, bikes, clothes, hotel rooms, workspace and even homes for the sake of cost savings and sustainability. As well as opening a broader range of consumer choices, the sharing economy has allowed a more intensive use of society’s supply of capital, whether it be for clothing, vehicles or real estate (see figure 8). Greater output for the same level of input is deflationary.

So, how long can this carry on? The answer is: probably quite a while. Mediocre aggregate demand alongside aggressively expanding supply has totally suppressed inflation. The US Federal Reserve has latitude not just to cut rates to support economic growth but to engage in further open-market activities if necessary. It might be that further monetary stimulus will, and possibly already has, created asset-price booms in stocks and the technology and commercial real estate sectors. But this does not accord with generally solid fundamentals in each of these markets. One of the benefits of slow and volatile growth is that, despite low interest rates, it has prevented the kind of heedless risk-taking behaviour that typically emerges late in the economic cycle. For once, there is no overhang of speculative real estate.

What could bring this sustained cycle to an end? A very major Middle Eastern war that impacts oil supply might do it. A major military confrontation between the U.S. and China, perhaps over Taiwan, would also be very problematic. Alternatively, a further wave of radical populism leading to anti-trade policies might further undermine corporate sentiment and the stock market – even after 10 years of growth, the US economy has yet tosubstantively lift the living standard of working-class people. A hard Brexit, and/or a further fracturing of the EU would be highly disruptive. But it is very hard at this stage to see an interest-rate-generated recession due to rising inflation. This is a quite different situation to any of the last four cycles in the last forty years.