Covid-19 may or may not trigger

Here’s the conundrum: invest with the madness or against the madness? Credit and financial markets have become increasingly reflexive as central

A recent Bloomberg Businessweek feature described the heavy concentration of the US fund management industry, where the big three firms own 22% of a typical constituent of the S&P 500 index, up from 13.5% in 2008. The determination of the US Federal Reserve to ‘first, do no harm’ to the US economy has convinced investors that 2020 will be another year of bumper returns as interest rates fall and the Fed’s balance sheet expands.

Voices of caution tend to be drowned out by the chorus of self-serving bull market opinion. The polarisation of political life is mirrored in the investment community, where confirmation bias is rife. Indeed, the invisible algorithms that run on our devices are carefully curating the messages we receive to give us more of what we like, and less of what we don’t.

Famously, in July 2007, Chuck Prince, then chief executive of Citigroup, told the Financial Times that global liquidity was enormous and only a significant disruptive event could create difficulty in the leveraged buyout market. “As long as the music is playing, you’ve got to get up and dance,” he said. “We’re still dancing.” Testifying before the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission in 2010, this quote came back to haunt him. Prince’s rationalisation before the panel could be summarised thus: it was a race to keep up with competitors who kept loosening lending standards and Citi couldn’t afford to drop out.

These same dynamics are in ample evidence today in the US corporate junk bond, leveraged loan and private equity markets, but the world of ‘new monetary policy tools’ has aggravated reflexivity and turned financial markets even more toxic. As Helen Thomas of Blonde Money observes, quantitative easing and the passive money machine have transformed the process of asset price formation. “Prices of assets used to reflect the probability of future risks and react accordingly when information changed. Now, it is only profitable to assume that everything is wonderful, until a risk becomes so immediate that the price adjusts suddenly in a step change,” she says.

In this brave new world, most of the time, it is highly lucrative to sell volatility using derivative instruments. While the Fed ‘has your back’, liquidity is plentiful and nothing goes wrong, then equity market put options will expire worthless and the premium becomes profit.

To asset managers, buying protection against adverse market moves seems just a waste of money and a drag on investment performance.

However, all this volatility selling leaves market makers with something called a long gamma position. As Blonde Money’s Thomas explains, whoever is left holding volatility must trade every day to cover the time decay inherent in their options.

They must buy every dip and sell every rally, and as trading ranges shrink, they must do so more often and in larger sizes to avoid a constant drag on their profits from ever-decreasing volatility. A mere 1.5% move in the S&P 500 index can turn (profitable) positive gamma into loss-making negative gamma. Everything is on a knife-edge. Similarly, BBB-rated and BB-rated corporate bonds can price close to perfection one day, only to fall off a cliff at the merest whiff of impairment.

On 3 January, former Fed chairman Ben Bernanke (remember him?) delivered a punchy speech at the Brookings Institution, singing the praises of the ‘new monetary tools’ which have been extensively deployed in the past decade. Bernanke is a cheerleader for the effectiveness of said tools, believing that the Fed has more than adequate firepower, in the form of QE and forward guidance, to fight the next recession.

He conceded that other tricks – constructive ambiguity regarding negative nominal interest rates, yield curve control or a moderate increase in the inflation target – might also come in handy. What he seems not to have considered is that the manipulation of financial conditions might already have lost its ability to transform economic outcomes.

Central bank models of economic behaviour – which inspire them to claim that the Fed still has the equivalent of 300 basis points of rate-cutting at its disposal – assume that the world is full of benign risk-takers, who interpret central bank signals as cues for increased consumption and capital formation.

In truth, there is a mixture of benign risk-takers, no risk-takers and malign risk-takers. In an artificial atmosphere of perpetually low interest rates, the proportion of charlatans and chancers – those who borrow recklessly with no intention or expectation to repay – rises exponentially.

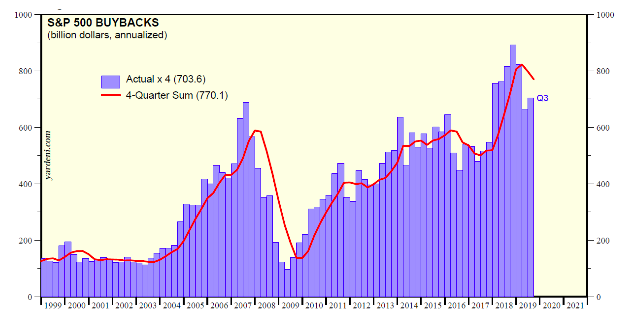

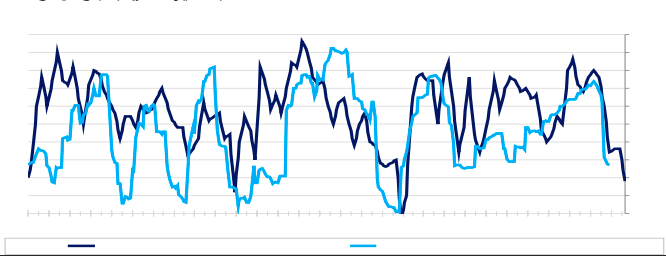

Figure 1 reinterprets global monetary policy as a pick-me-up, or put-me-down, for CEO confidence. It suggests that even-lower interest rates will be needed to assuage the fears of big business. Even if the slump in business confidence can be arrested, global economic recovery is not guaranteed. A surge in financial asset prices predicated on ever-easier financial conditions will hit the rocks as corporate profitability crumbles and share buy-backs (figure 2) are cancelled.

Figure 1: How global monetary policy influences CEO confidence

Figure 2: As share buy-backs are cancelled in response to falling corporate profitability, asset prices will drop