Long term interest rates, in real and nominal terms, have fallen continuously since the early 1980s, and yields on commercial real estate have come down with them. Most recent analysis, suggests that it is real rather than nominal interest rates that dive property yields. Why?

So, what has driven long term real interest rates down? The fall in inflation is the main factor behind the decline in nominalinterest rates. The decline in real(i.e. inflation adjusted) interest rates has been more difficult to explain, but CBRE Research and others, point to the centrality of demographic change.

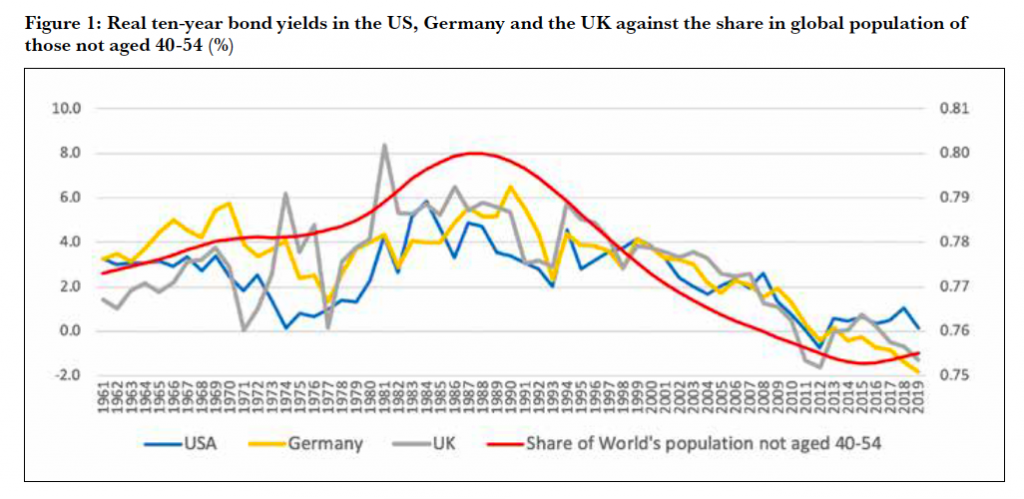

Specifically, tt is the growth, as a percentage of the global population, of the 40 to 54 age group that has driven down real bond yields, and property yields as well. Figure 1 illustrates the trend. It shows real 10-year bond yields in the United States, Germany and the UK alongside a line indicating the share of global population of those not aged 40 to 54. That line falls in the period since 1985, indicating that the proportion of those aged 40 to 54 has risen. Econometrics, not shown here, confirms a statistically significant relationship.

Correlation is not causation: but the economics is also persuasive. The 40 to 54 age cohort has a high propensity to save, mainly for retirement, but also for childrens’ college education and for other forms of bequest. Real interest rates are determined in global capital markets by demand and supply. Over the last 30 years relentless demographic change has , boosted the supply of capital relative to demand so the price of money has fallen. There is another, even more subtle factor at work, also driven by demographics. As the global population has aged, and people have become concerned to be able to support themselves in old age, the preference for risk free assets has increased. As savings have grown more of those savings have targeted safe government bonds.

Is demographics, and the increased supply of capital, the only factor? No, the demand for funds by companies for productive investment has also declined. Capital goods are relatively cheaper than they were so companies need to spend less to create productive capacity. It is also possible that societal ageing is behind decline in productivity growth in the advanced economies over the last twenty years. Lower productivity growth gives companies less motivation to invest in productive capacity.

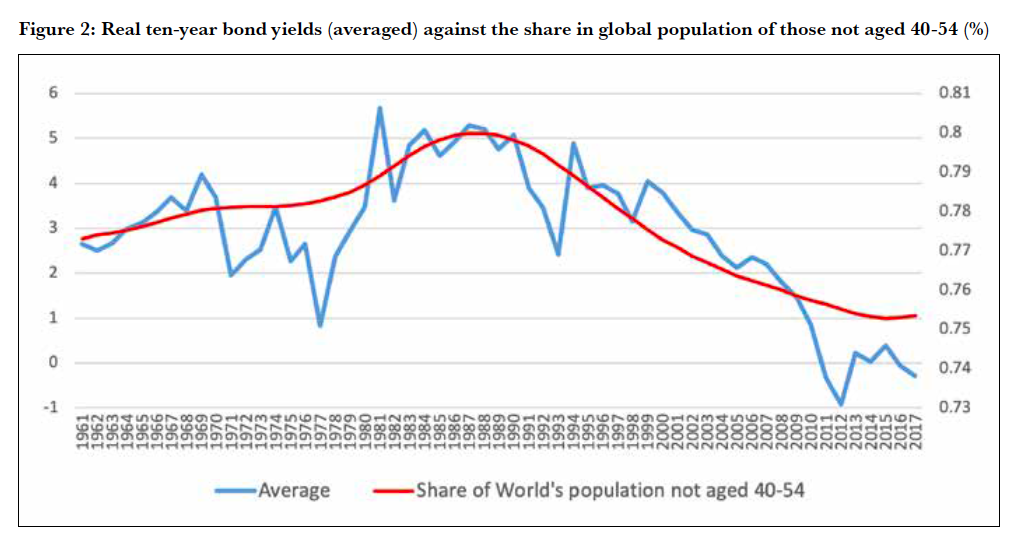

Figure 2 suggests one other influence on long term interest rates. It has the same data as Figure 1, but for ease of explanation, the country bond rates are averaged, and the chart scales are altered. There are two periods in which bond rates have sunk below the level suggested by the principle demographic trend: the 1970s and the 2010s. In these periods, investors experienced acute financial uncertainty. In the 1970s, the U.S. dollar lost its link to gold. In the 2010s, the banking system nearly failed. In both cases, the demand for ‘riskless assets’ surged.

What’s next? It is hard to see where a productive investment boom will come from, unless governments start to borrow big-time for infrastructure investment (which they should, but probably won’t). Central banks have recently restarted the QE programs, so it unlikely that financial insecurity is going away any time soon. Most importantly, demographics suggests that the overwhelming supply of capital won’t dry up. The proportion of those in the high savings 40 to 54 age group continues at about the same level for the next ten years. Real interest rates and property yields are set to stay low for some time yet.

Richard Barkham and Neil Blake, Global Chief Economist and Global Head of Forecasting at CBRE, respectively.