It is my experience that, when travelling, the best way to understand a country is to follow in the footsteps of an artist or architect of that country’s culture. This leads to some unexpected results. On my last visit to Japan, I discovered some of Tadao Ando’s early and more obscure churches. These are often located in the

(Photograph by Houston Morris Architects)

Ando’s churches are certainly beautiful enough to inspire the taking up of a faith. Ostensibly they have the same root of much modernism and are inspired by that architectural figure, who is both derided and venerated in equal measure, Le Corbusier. Ando started out his career as a boxer but switched to architecture in spite of having no formal training. He visited Europe for the first time from his native Japan in 1963 and arrived at Le Corbusier’s office, but unfortunately, two weeks after the great man had died. Although Ando had just missed meeting his great hero in real life, the autodidact remained undaunted and has since had a remarkable career, building over 400 buildings including some of the finest and most praised museums in the world.

It has just been announced that the opening of Francois Pinault’s new Tadao Ando designed $170 million museum in Paris’s former stock exchange has been delayed, presumably as a result of corona virus issues, until June of this year. Pinault, who owns a number of well-known luxury good companies including Christies auction house and many other well-known brands, has already used Ando for the conversion of the classical Palazzo Grassi on the Grand Canal and the former customs union, the Punta del Dogana in Venice. Tadao Ando appears to be the billionaire’s go-to architect but the supreme irony of this is that his architecture has its origin in Brutalism, that most socially progressive and aggressive movement in architecture. Brutalism was named by the critic, Reyner Banham amongst others in 1955, after the French term for raw concrete, ‘breton brut’.

Brutalism is the marmite of architectural styles in that you either love it or loathe it. It has a certain cult following among the cognoscenti now that it is so out of fashion. They will go and search out the most obscure post war Eastern European housing blocks, and laud them with praise equal to that of Le Corbusier’s original brutalist masterpiece, the Unite d’Habitation. Likewise, a town hall in Boston will be compared by them on an equal footing to the civic buildings of Brazilia. In contrast, there are others (and not just traditionalists of the Betjeman persuasion) who will impulsively spit at the mere mention of a new town or concrete. Words such as ‘carbuncle’, ‘bunker’ and ‘monstrosity’ emanate almost immediately from their lips. But somehow Ando is able to tread a fine line in his buildings, managing to be appreciated by both camps.

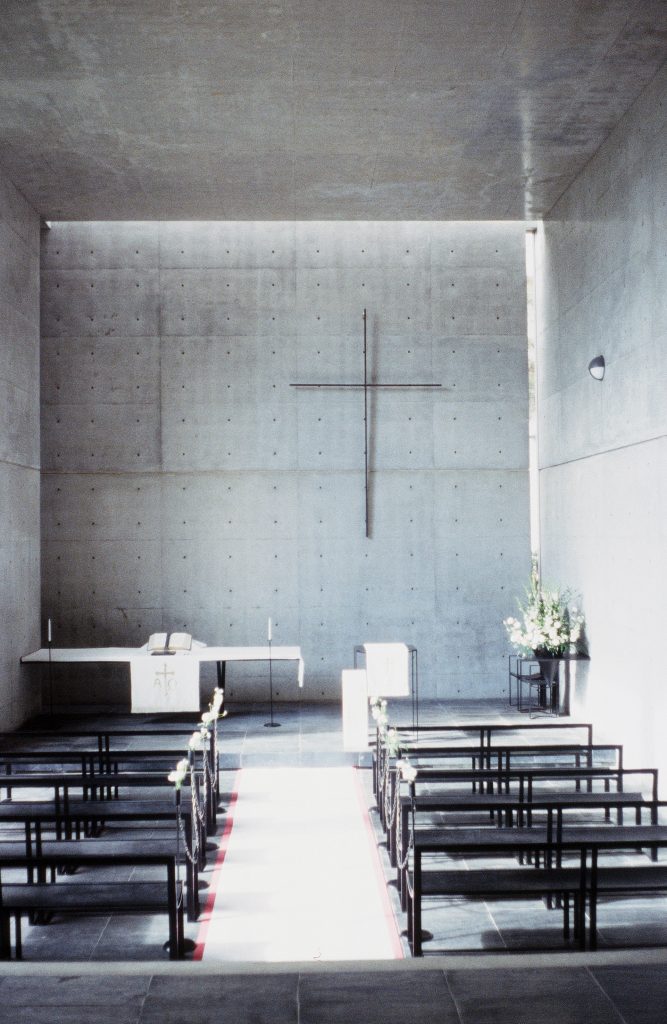

Although reinforced concrete (Ando’s material of choice) is the same as that used by the Brutalists, in many ways his work is the opposite of Brutalist architecture. When building in reinforced concrete, the key to the finish is the wooden shuttering (or formwork) into which the liquid concrete is poured. Brutalism often celebrated the texture of the concrete through the use of roughhewn wood formwork or coarse aggregate at the edges or even the use of a pneumatic drill, post setting, to create an exposed rough effect. In contrast, Ando’s walls are smooth and polished. The position of the ties that hold the formwork together are spread in a rational visible grid and all tie holes are filled in and polished after setting. On site supervision is one of the aspects of construction that most architects struggle with and with the ‘wet’ trades in particular. Poured concrete is notoriously difficult to get right but Ando manages it with a precision that is impressive even by the very high standards of Japanese construction.

(Photograph by Houston Morris Architects)

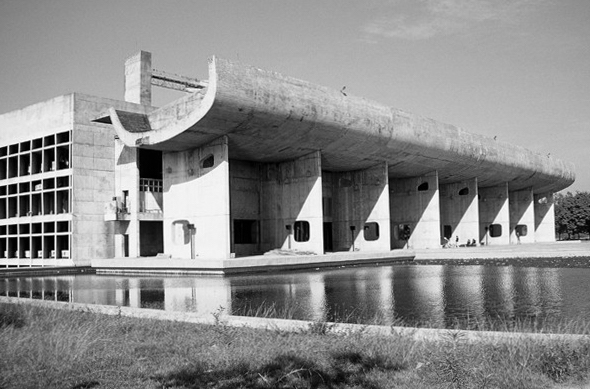

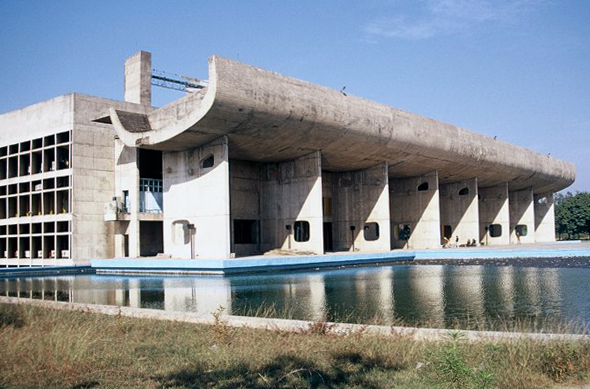

Despite the arch brutalist Le Corbusier’s great success, ranging from private house commissions to entire cities, the pre-eminent twentieth century architectural thinker’s detailing was often poor. Anyone who has visited the highly praised and photographed buildings of Chandigarh will be appalled by the shoddy workmanship. Perhaps, after all, it was a blessing that Ando narrowly missed meeting his architectural hero and the Japanese architect’s love of fine detailing was never questioned.

This precision is the reason Ando manages to play with light so well. His walls and windows seem uplifting, soaring and even spiritual. The walls appear wafer thin, even sensual, whereas much of brutalism celebrates the contrast of light and shadow, and an almost gothic celebration of the dark and scary shadow. It is not just the geometry of intersecting platonic shapes but the abstraction of the building into the separate elements, wall, ceiling and floor that make his buildings into calming and soothing sculptures. Window frames are rarely visible but the slits or openings are, so you get this reduction of the building to pure sculpture with light. This is where the power of Ando’s architecture lies and is achieved through a masterful control of the architectural detail.

It is rare that we achieve this type of precision in this country. Possibly Peter and Alison Smithson’s Economist building in St. James, London comes close but this is not, strictly speaking, built from poured concrete. I don’t think our lack of precision or flair can be solely attributed to our wet and inhospitable climate. Some believe that there must be a cultural reason that Ando is able to achieve such godlike spaces and that it must stem from a Shinto Japanese Buddhist tradition of calm.

What fascinates me, though, is that after the socially and community based architecture of public building that was jettisoned in the nineteen eighties, it is architects like Ando who have thrived and mostly from the private commissions of wealthy individuals. This is true of the other star architects of today too. Rem Koolhaus, David Chipperfield and Zaha Hadid have all produced dynamic sculptural buildings as daring as any brutalist. Yet they have not tackled the essentials of modern living such as social housing, hospitals, libraries and transport buildings which were the bread and butter of the brutalists.

Due for completion in June 2020

image ©

It might be worth speculating about what might happen in the post Corona virus world. Will there be a shift in thinking? Might there be a new political will to build more interesting publicly funded architecture? Maybe we will see a more national and progressive approach to building. Maybe there will be a move away from the public/private partnerships that produce such banal places to live and work. It might be that architects wrestle back the ground they lost to the large scale housing developers who land us with dull, traditionally styled suburban housing. Architects might again be used not just for prestige projects but also for producing our vernacular buildings, which are, after all, also part of our cultural heritage. It might be that a version of the modernist dream finally comes true and anyone and everyone, and not just French billionaires, can enjoy living and working in a smooth concrete, light filled masterpieces designed by a quality architect such as Tadao Ando. We have seen that we are vulnerable in a world where the cost advantages of unfettered trade and travel also can expose us to physical danger. It might be that self-sufficiency and sustainability goes to the top of politicians’ agendas. Could there be a new approach, post Covid 19, that takes hold, similar to what happened after the Second World War but not in the aggressive, divisive way that Brutalism proposed? Perhaps we may see a new spirit of togetherness that enables us to pursue a more sustainable, community based and locally sourced architecture which is both more architecturally interesting and, indeed, we hope, uplifting in a similar way to the buildings of Tadao Ando.