The ‘potato cycle’ is a staple (sic) of the economics menu. The first thing, in fact, I was taught on the first day I began as an undergraduate, so, so many years ago. This simple rule uses the demand and supply curves for potatoes to illustrate how negative shocks to short-term supply, for whatever reason, trigger production responses. In the vast majority of cases, this returns the inflated price to what the fundamentals of the good’s production functions determine it should be.

What the potato model shows is that, for the most part, an upwards shock to the price of a fungible/commoditised good – of which the potato is a mere generic example – triggers a supply response. This positive supply response reverts the price back to its fundamentally determined level. And, to be clear, the model predicts that in almost all cases where supply is responsive, this price reversion is to the marginal cost of production. Straightforward stuff indeed. And yet, as simple as this model is, we have failed to employ it where it is perfectly sensible to do so, in a market which has recently seen a short-term negative supply shock, the energy sector. Indeed, any economist who denies the global energy market is competitive is far from competent.

The reality is that the near-term energy price shock we have suffered in the aftermath of events in Ukraine has set off a train of supply events, which will inevitably and quickly send the price of oil and gas – in dollar’s – back to its marginal cost of supply (and so too most other commodities).

“The gap between the market price for energy and the much lower fundamental marginal cost of supply will see new channels of production open up far and wide around the world”

One cannot stress enough how the marginal cost of energy in all its forms has not materially changed since the invasion of Ukraine. From a surge in ethanol production in Brazil, to oil sands in Canada and nuclear in France, Venezuela returning to the global oil-supply fold, and Nigeria and Angola ramping up output, and so too the Gulf states et al, the gap between the market price for energy and the much lower fundamental marginal cost of supply will see new channels of production open up far and wide around the world. This extends to all sorts of varied forms of origination, possibly even potatoes! As for timing, the speed it will take for a new supply to come on stream correlates strongly to the size of the overshoot of market price – and what we have witnessed is a large overshoot. Remember too, that in relation to, say, ethanol production, the cereal crop cycle is between two and three months, with moreover the same arable land being reusable quickly. So, while we may not have quite noticed it yet, there is a huge increase in the supply of grain for food, and grain for ethanol, set to hit the global market. There is also new supply coming from oil and gas and all other substitutes for energy. Those who are creating monetary models – inflation and growth forecasts – assuming energy prices remain stubbornly high, need to explain to me why the potato model does not apply to energy?

Yes, for a while the world will have two energy markets. One made up of nations who do not discriminate in who they buy from, the second comprising those who self-restrict their suppliers; the latter paying a premium for their indulgence. This accepted, the pricing gap will close. After all, those energy suppliers not on the ‘restricted list’ will direct their production efforts to where the price they get is highest. And such arbitrage cannot fail to close the energy pricing gap.

Let me return to the first day as an economics undergraduate. Back in 1984, the Cold War/Iron Curtain made things very chilly at a time when there was no Chinese economy in any meaningful way. All those years ago, Japan was an economic giant with the yen poised for a rapid doubling, a surge in wealth which Tokyo would squander. A time when the UK jobs market was plagued by high and persistent unemployment. Back then the supply of oil was in the tight grips of a seemingly all powerful OPEC cartel; the ongoing bloody Iran/Iraq war constraining supply all the more. Thankfully things have now changed.

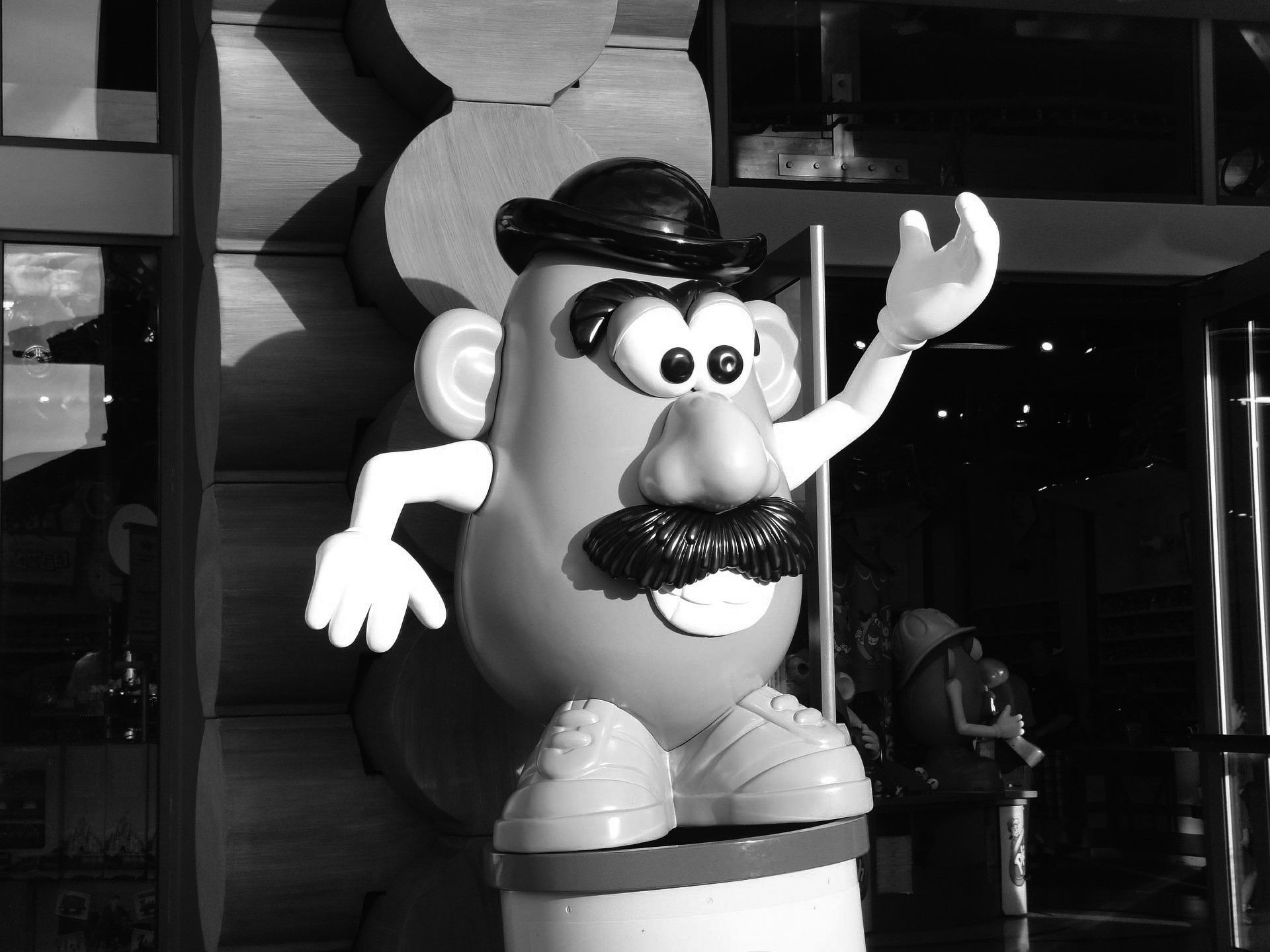

To be frank then, only a Mr Potato Head could believe global energy prices will not fall and do so rather quickly. Now, there’s an image which cannot fail to bring to mind the Bank of England Governor and his projections for persistently high energy prices.