The real estate industry has a lot to learn about human behaviour and happiness: dissatisfied occupiers won’t stick around.

Richard Thaler, the behavioural economist, received long overdue recognition when he won the Nobel Prize for Economics in 2017. This opened many people’s eyes to the value in understanding the psychological reasoning behind decision-making. At a very simplistic level, traditional economic theory suggests that people are rational and self-interested in making judgments about their life. A behavioural view might take a counterpoint approach and infer that people, while overall operating as rational beings, have the capacity and in some cases the compunction to make seemingly irrational decisions.

For example, before the age of five, children are very hesitant to conform to the rationale behind delayed gratification. Given a choice between one biscuit now or two biscuits in 15 minutes’ time, they will grab the one on offer. Adults too can sometimes prefer the certainty of an immediate reward and not want to risk a reward being snatched away should something go wrong.

In real estate we are seeing a slow realisation that people are indeed irrational at times and have a differing set of requirements based on their changing behaviour. The people who occupy buildings, such as office workers, have become more demanding, and we must adapt how we operate to better meet their evolving needs. Behaviour is defined as the response of individuals or groups of people to internal and external stimuli. On a more basic level, this means how people react when things happen. These stimuli can be emotional, they can be environmental factors – almost anything in our lives can be viewed as having an influence on the way we behave.

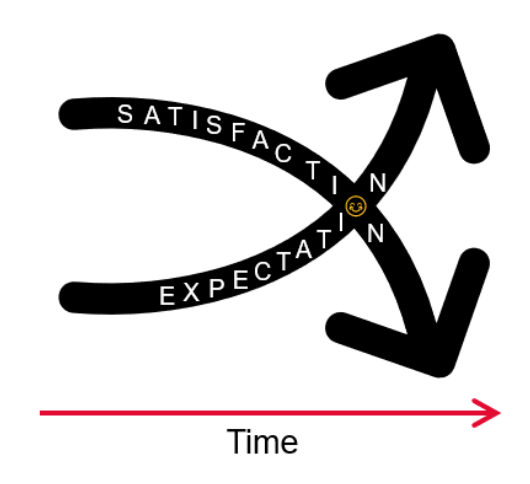

As a society our behaviour has changed dramatically over the past 50 or so years. Levels of satisfaction have decreased while expectation levels have risen. In the immediate post-war period, even unbounded fresh fruit or unrationed confectionary was a dream for many people. Then came two big game-changers: family cars and television. Access to a car gave instant freedom – the chance to go anywhere at any time. Yes, since then we’ve had bigger and better vehicles, but that dream of taking the family to the coast for the day was realised more than 50 years ago.

The 1953 coronation of Elizabeth II is imprinted on the minds of many as the day that television entered our lives. On the day itself, 20.4m people watched on television (considering there were only 2.7m television sets in the country, this meant an average of 7.5 people per set, excluding children). The 9-inch, goldfish-bowl-shaped screen holding shadowy figures transfixed neighbourhoods, with people craning their necks to see over heads of those in front of them. Yes, we now have 80-inch OLED curved-screen televisions, we can access content from anywhere in the world and we have hundreds of channels to choose from – but the core principle of home access to entertainment hasn’t changed.

As a result of being mobile and being entertained, people’s expectation levels began to grow. They will no longer settle for ‘something’; they want ‘everything’. Most people on an average income have the potential to access the latest smartphone, the fastest games console or a holiday in some far-flung place. The simple truth is that when you can have anything, your satisfaction at receiving a product or a service is lessened. We are never going to say we want something to be more expensive, of worse quality or not available until some point in the future – we just expect it all, and now.

But what does this have to do with real estate? The changes in behaviour that come from raised levels of expectation have a direct influence on how real estate operates. Occupiers, as individuals, call upon their experiences in other areas of their lives: in hotels, at airports, in forward-thinking retail environments. All these customer-centric businesses have changed the level of what is deemed acceptable. Buildings are now more than a physical entity: it isn’t just about walls any more.

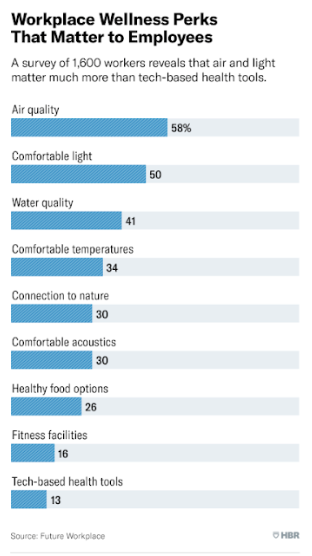

Moreover, the divides between live, work and play are more blurred than ever. As a result of technological advances and a greater level of awareness of what is possible, to many people going to a ‘place’ to work is anathema. And there is no such thing as a one-size-fit-all model. Meanwhile, the chasm between what people want and what they experience is perhaps widened by the belief of many in real estate that they understand what people (occupiers) want. Money is spent on a myriad technological solutions to problems that may not even exist or be a minor concern at best, as the diagram here shows.

The wellness elements that drive happiness are as simple as better light, air and water. It’s a tired saying but remains relevant: you must get the basics right. The Harvard Business Review says a high-quality workplace can cut average absenteeism by four days a year. Employees who are satisfied with their workplace are 16% more productive, 18% more likely to stay and 30% more attracted to their company over competitors. The Pursuit of Office Happiness, a report funded by Staples, goes even further and states that one in five people find their office depressing, 70% say they would feel more valued if their employer invested in the workplace and almost a third claim to be ashamed of their workplace.

It is clear from these and similar results that many in the real estate industry just don’t get it. It’s time they did. The concept of an employer being at least partly responsible for a worker’s happiness might have been laughed at in the 20th century, but that is no longer the case. The obvious business benefits are clear to see. In an office environment that recognises people’s changing needs, individuals will be happier, more productive and healthier, and they will be advocates for their employer. If the real estate industry is in search of a more meaningful metric, it could do worse than look to measure happiness per square metre.