Originally published October 2022.

After nine years of enticing first time buyers (FTBs) into – and consequently inflating the prices of – new build, help-to-buy (HTB) is finally coming to an end. Over in the wider mortgage market, recent monetary chaos has spiked rates such that it has further lifted the first rung of the housing ladder from the reach of aspirational FTBs. Now, a great many will see the end of HTB, and far less affordable and accessible mortgage terms for FTBs as the last thing the UK’s beleaguered housing market needs. Well, I see matters very differently.

Each year, well over half a million British-born young adults leave higher education; be it gaining their first or postgraduate degree. The number has risen to such lofty highs because, back in 1997, newly installed Prime Minister “education, education, education” Blair insisted that at least half of 17/18-year-olds should continue to university. To achieve as much, he gave higher education institutions (HEIs) the student-fee incentive to significantly add capacity.

Now, some of those early 20y-something Britons leaving full-time higher education go travelling, choose not to work or simply cannot find suitable employment. This accepted, around 80% swiftly enter take-up employment. True, some of these return to their parental home and many earn no more than had they not been burdened by a student loan. It is, however, those who remain in the UK and quickly find ‘rewarding work’ that I wish to focus on in what follows. I do so with one aim: to show that far from being a ‘sure-fire catalyst’ for a collapse in UK house prices writ large, a less generous mortgage market for FTBs will act to drive-up residential tenant demand. Drive up and so support the buy-to-let (BTL) side of the UK housing market; a market we are being (mis)informed, will flounder.

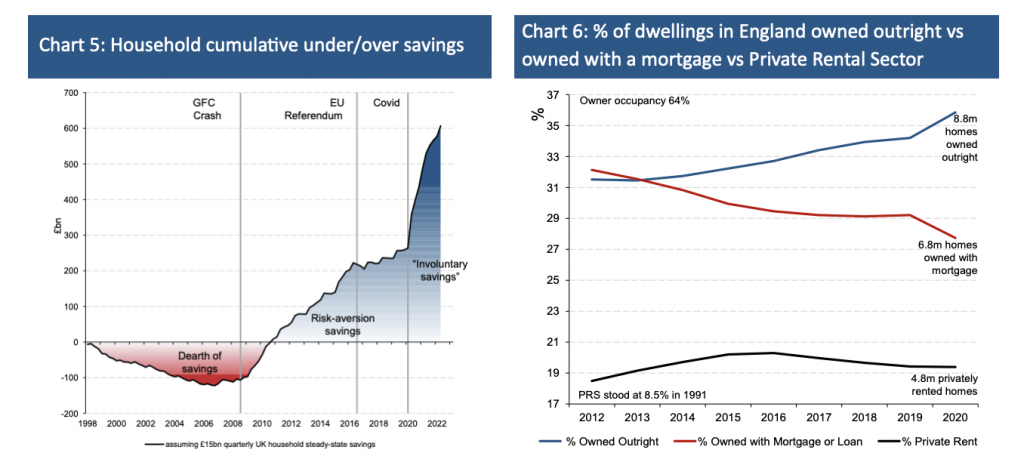

In total there are just over two million British-born young adults in full-time higher education. This is a substantial increase from as recently as the 90s (Charts 1 and 2). A great many of these studious young-adult Britons live in a part of the UK’s private rental sector (PRS) which has been newly developed specifically for them. Before I return to the large class of graduates demanding homes now that did not exist in the late 80s, I would like to spend a moment considering other marked differences now from then.

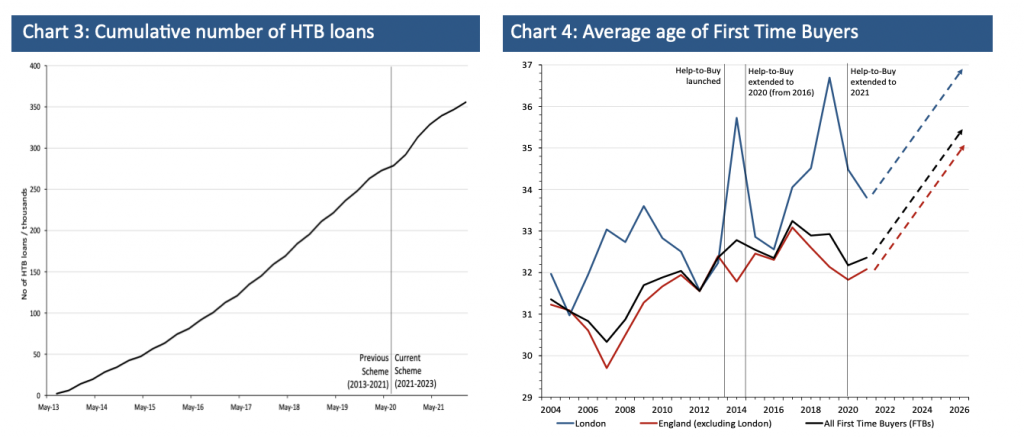

“We must not forget that as the university population has grown significantly, the UK has annually recorded migratory flows of record proportions, injecting young adults into places which had hitherto been abandoned by the youth”

The simple truth is that those using the housing crash of ‘89 as a yardstick for what awaits today completely fail to understand how different matters are. Very different in the nature of the mortgage market – a record high number of ungeared homeowners (Chart 6) and record low loan-to-values (LTVs) for those with mortgages, of which a great many have two-year-plus fixed rates. Different too in that the residential market has a rental class substantially larger than back in ‘89 because of the surge in the quantum of full-time students. Indeed, as each new class of these graduate, they move on to be rental tenants elsewhere. We must not forget that as the university population has grown significantly, the UK has annually recorded migratory flows of record proportions, injecting young adults into places which had hitherto been abandoned by the youth. There will be those who, whilst accepting we have not gone back to ’89, will claim we have all the same journeyed in time, but instead to ‘08. Here again comparisons are grossly misleading, however much the Governor of the Bank of England would claim they are eerily appropriate.

Source: HESA, Toscafund

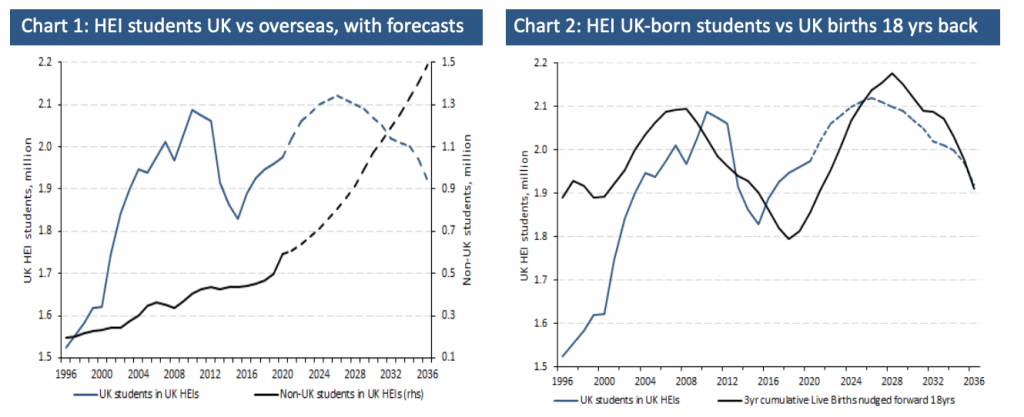

The UK’s large cohort of young new graduates has created an entirely new class of renter. A ‘class’ that is, for the most part, a renter with the keen ambition to be an owner-occupier as early as financially possible. In considering this group, I wish to use the analogy of a conveyor system transporting UK-born 17/18-year-olds into university, where they are renters, then out of those learned institutions to the world of work, but still in rental accommodation, and thereafter, homeownership. Statistically, the average age of FTBs is around 32 for the UK, excluding London, and a little older at around 34 for those buying in the capital (Chart 4).

Give or take a year or two, the evidence suggests graduates spend three times as many years as tenants across the private rental sector as they did as student tenants. That said, the HTB scheme, which began in 2013, provided a subsidised step onto the UK housing ownership ladder. The uptake of which to date has been just over a third of a million (Chart 3). Continuing with the conveyor analogy, what HTB did was redirect the flow of young renters keen to become owner-occupiers into the niche market of new-build. As well as HTB being a very lucrative redirection for homebuilders, it acted to regularly remove those taking up the scheme from remaining in the PRS.

HTB’s ending will ensure that those that have been in the PRS for, say, six or seven years, cannot as easily become FTBs. Nowhere near as easily, that is, as they would like to be and nowhere as easily as those who came before them on the conveyor. We need to also consider how the shift-up in mortgage rates facing those keen to be FTBs will force all the more young adults to stay as PRS tenants. Young working adults, it has to be added, who in turn have never had as strong a bargaining hand to demand pay rises. As a result of these twin events, the conveyor those in their late 20s and early 30s are on will nowhere as easily as before detour them into home ownership (Chart 6); it will, in short, keep them far longer as PRS tenants. One must appreciate in this regard we are talking of a building up of enforced renters with each passing quarter. Tenants who, until recently, vacated the homes they rented to move to their own home, leaving behind properties to be filled by those behind them on the conveyor. The resulting build-up of entrapped tenants cannot fail to create a supply shortage and as a result lift rents. Lift rents, and so lift PRS yields, which then lift demand from BTL investors. This, in turn, will at the very least support property prices and across many parts of England, lift them.

Who then will be these BTL investors? Well, British households in aggregate are sitting on hundreds of billions of involuntary savings – see Chart 5. Against this monetary backdrop, the idea of becoming a landlord or adding to one’s rental property portfolio will seem ever more comparatively attractive. Overlay a currency which can only attract more fee-paying students from overseas (Chart 1) and the UK residential market does not look anything like as dire as many claim it does. Yes, new built homes will record lower prices – possibly sizeably lower – than hitherto. This eventuality was always certain once HTB ended. Those predicting, however, that home prices across England writ large are certain to fall in a distressed manner, show just how uneducated they are in a post-modern economy. An economy where those keen to own their own home, but frustratingly stuck in PRS, do not undermine the strength in England’s residential market, but simply change the nature of its tenure structure and strength.