Originally published November 2021.

What could possibly go wrong?

“Africa has a significant role to play in the energy transition. We are home to a third of the world’s mineral reserves and 14% of the world’s forests… Our view is that the energy transition needs to be balanced. It needs to be just. It needs to consider the fact that most African countries rely on fossil fuels for revenue and there is a need to continue to develop fossil fuels, especially natural gas, which is quite clean. For us to have the base load that we need, there is a need for balance.”

Those were the words of Samaila Zubairu, president and CEO of the Africa Finance Corporation speaking at the AFC Great Debate held at the recent Nordic Africa Business Summit shortly before the COP26 climate ‘horse trading’ event was about to begin.

So, what is ‘just’?

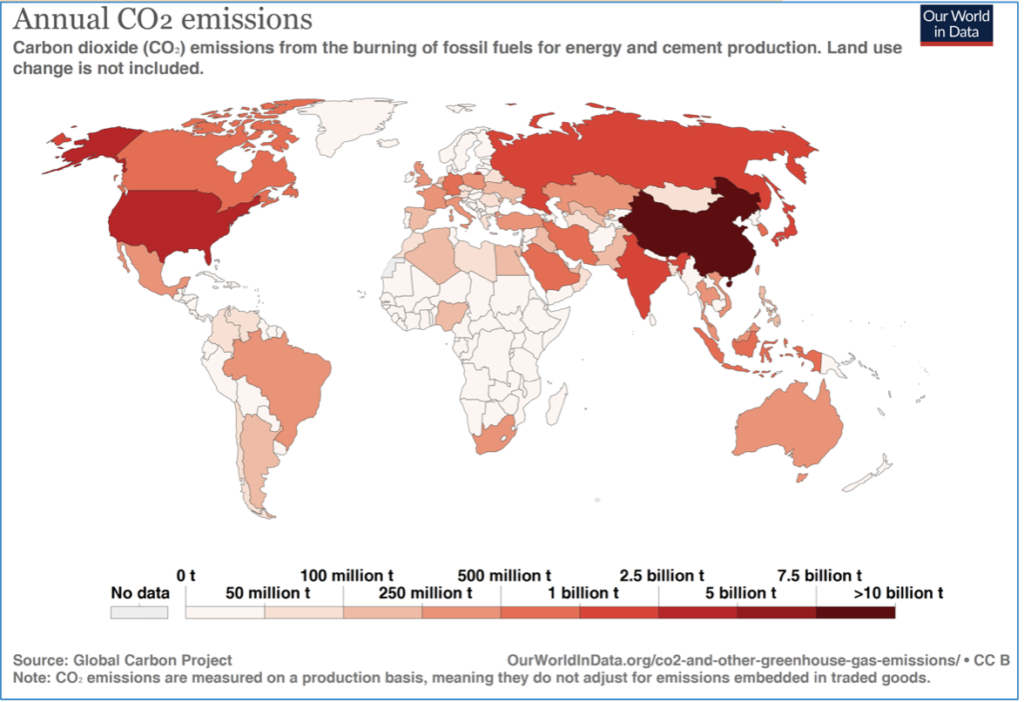

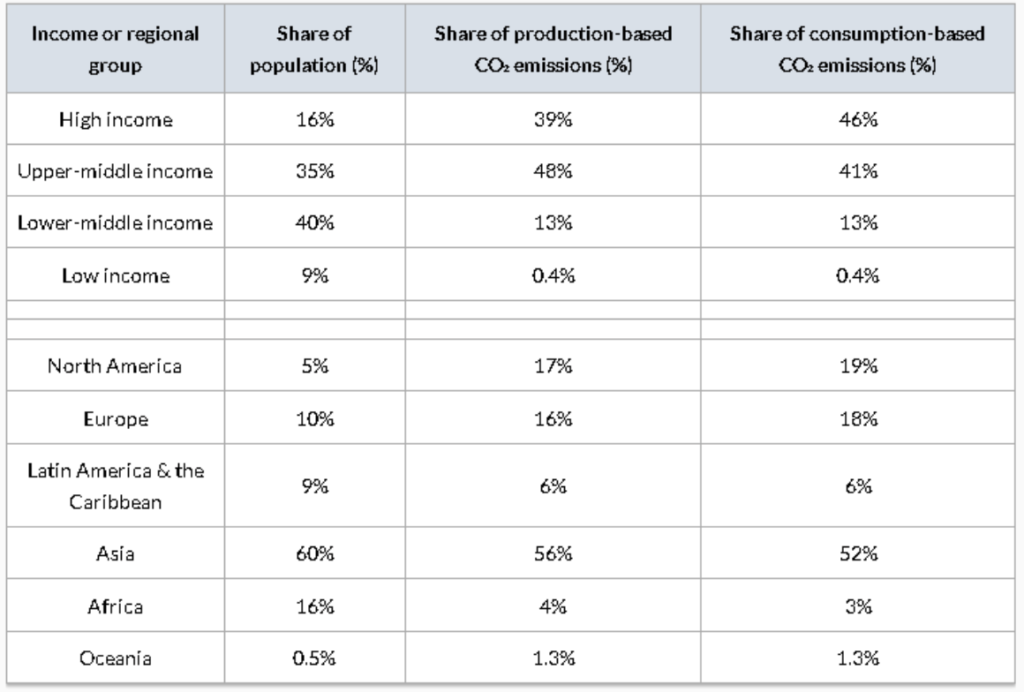

Looking at the global distribution of absolute emission levels they indicate a global north/south divide. That’s especially impactful with regards to sub-Saharan Africa, where most countries didn’t see any significant absolute increase in CO2 emissions at all over the past few decades.

Unsurprisingly CO2 emissions are correlated to income generation and economic growth, i.e., the better off a country is, the higher its CO2 emission.

That’s where it gets tricky. Assuming equal CO2 pollution rights across the world, the most striking imbalance is found in low-income areas and therefore a majority African countries. Whereas folks in North America, Europe and (if it would have been shown separately) China consume more than their fair share of both, production and consumption-based CO2 emissions, Africa actually has a ‘pollution gap’.

That’s obviously not an equitable situation and therefore is a major point of contention understandably brought up by African negotiators at COP26.

With the world’s attention focused on climate action it is often overlooked that while climate action is on most people’s mind when thinking about sustainability, it is only one out of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDG’s) adopted by UN member states back in 2015.

Looking at other critical SDG’s, like SDG #1 No poverty, SDG #2 Zero hunger and SDG #7 Affordable and clean energy, it soon becomes clear that most are closely tied to economic uplift which in turn needs to be powered by sufficient energy availability and affordability.

The most important distinction between SDG #13 – Climate action – and pretty much all others, is that it is now affecting people on a global scale, mainly through extreme weather patterns including wild fires, flooding and draughts as well as hurricanes. This commonality raises its profile, attracts attention and funding. However, it’s closely linked to critical other SDG’s with the main difference that those are disproportionally affecting people in poorer parts of the world, in particular sub-Saharan Africa.

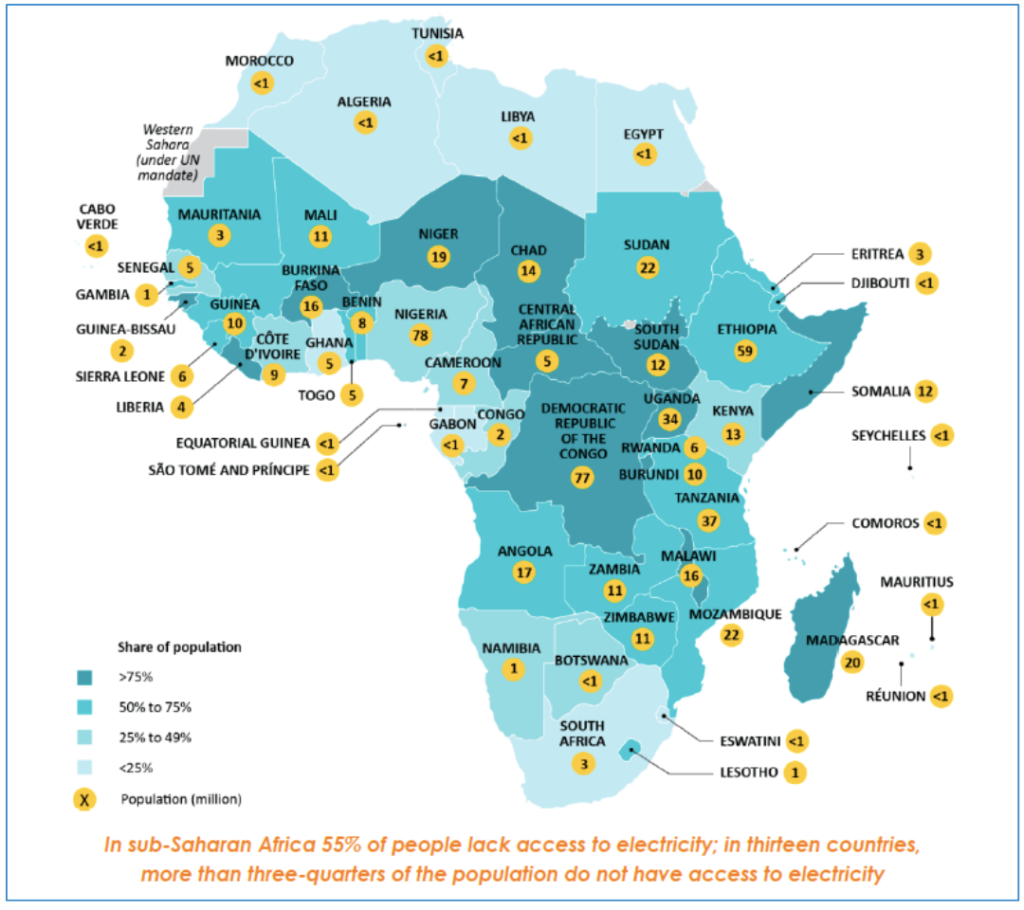

Energy access and affordability are closely linked to economic uplift. However, energy availability alone is a far cry from what is needed for both industry and consumers in large parts of sub-Saharan Africa.

Population without access to electricity in Africa (2018)

While there are seemingly ‘islands of plenty’, mismanagement and graft, like in the case of South African’s ESKOM resulting in currently up to six hours of daily load shedding, make even those bright spots look questionable. The resulting economic loss (interrupted Zoom calls due to unpowered cell towers are only the tip of the iceberg) are significant and mounting.

So, how can we achieve better energy availability and affordability across the continent and, most importantly, how should these initiatives be financed?

The supply side can be roughly divided into two big categories: green and, well, greenish.

The potential from using cost-effective solar power and concentrated solar (or a combination thereof) installations, stands out and far outstrips demand. However, space limitations in densely populated areas create land-use competition with, for instance, agriculture.

Hydropower, long a main energy source for a number of countries in SSA, becomes more contentious these days given its environmental impacts and cross-border disputes, like in the case of the Ethiopian Great Renaissance dam. In addition, a much more volatile climate is leading to insufficient water levels, as is the case of the Kariba dam spanning the Zambezi as a major power source for Zambia and Zimbabwe.

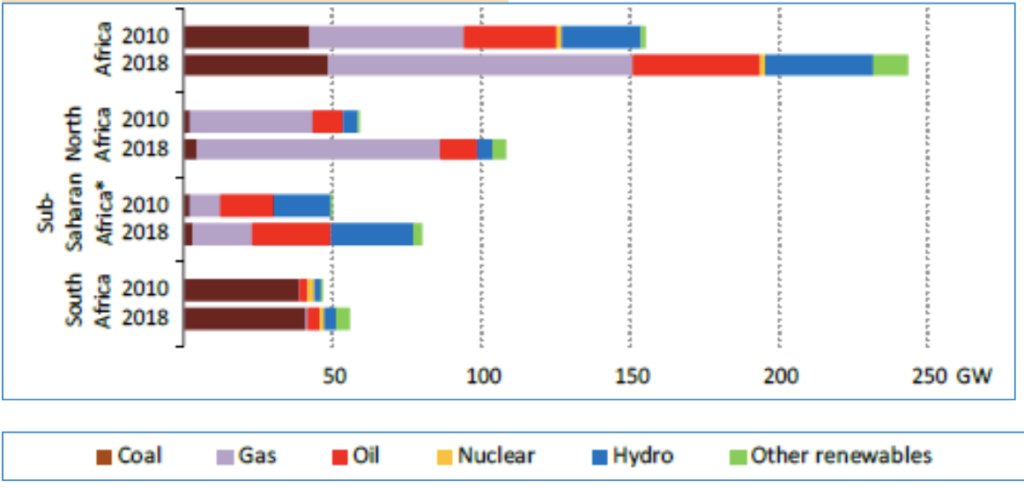

Fossil fuels are (and are likely to remain for the foreseeable future) the main energy source for the continent, despite a slow shift to greener technologies.

Installed power generation capacity by fuel (2018)

That’s where it gets tricky. The world’s shift to decarbonise significantly impacts energy generation investments as well as the political framework of international development finance. As a result, a number of countries announced the intention to link their direct and indirect development finance for Africa and other developing regions primarily or exclusively to green energy projects. This could prove to be catastrophic for some African countries on a number of levels. One is obviously demand suppression for hydrocarbons due to altered global demand patterns. The other is the unavailability of financing for fossil fuel energy generation projects to close the general supply gaps in most African countries.

What would a compromise look like?

Financing of carbon capture technologies for existing oil and gas extraction projects to reduce their carbon footprint is one low-hanging fruit element. Global carbon finance in the form of subsidised green bonds and/or a carbon credit trading scheme between African countries with low-carbon intensity and high-carbon emitting countries in the developed world would be another way. The underlying idea is for Africans to forfeit their ‘right to pollute’ by selling it to those who use more than their fair share of pollution rights, especially developed countries in Europe, but also North America and China.

Both subsidised green bonds and carbon credits would provide ample funding to African countries to (re) build their energy infrastructure.

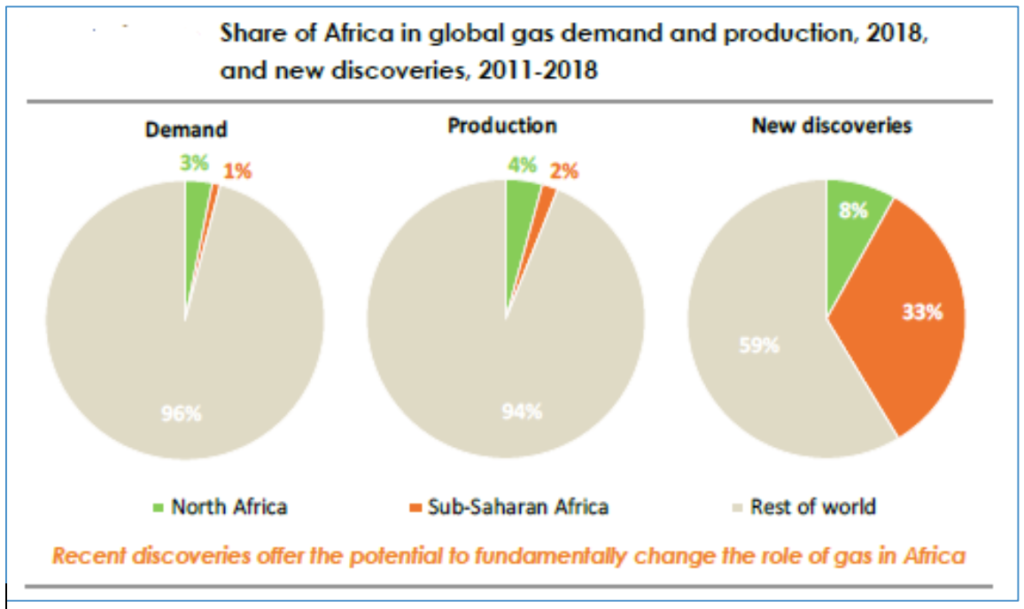

Another way would be to provide phased carbon-emission carve-outs for African countries to use fossil fuels as part of their energy mix going forward, in particular to provide baseloads for volatile renewables. (Relatively) green natural gas technologies, like dual-cycle power plants, provide significant potential. Such a carbon carve-out combined with declining-scale arrangements could also support fossil-fuel exporting countries in North and West Africa to implement structural economic reforms without a potentially devastating shock therapy. The recently enacted African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA), but also the rearrangement of supply chains driven by Covid and political disharmony elsewhere provide a promising backdrop.

Especially a balanced approach for sub-Saharan Africa’s ability to use and export natural gas, one of the key global bridge technologies required to ensure energy baseloads, will be crucial. This becomes obvious when considering SSA’s rising share of international gas markets as outlined below.

The recent last-minute COP26 concessions made to India for the extended use of coal-generated power provide an interesting precedent for particular carve-outs and may provide an argument for African countries in bilateral discussions with capital providers.

What other tools would be available to alleviate energy poverty on the continent?

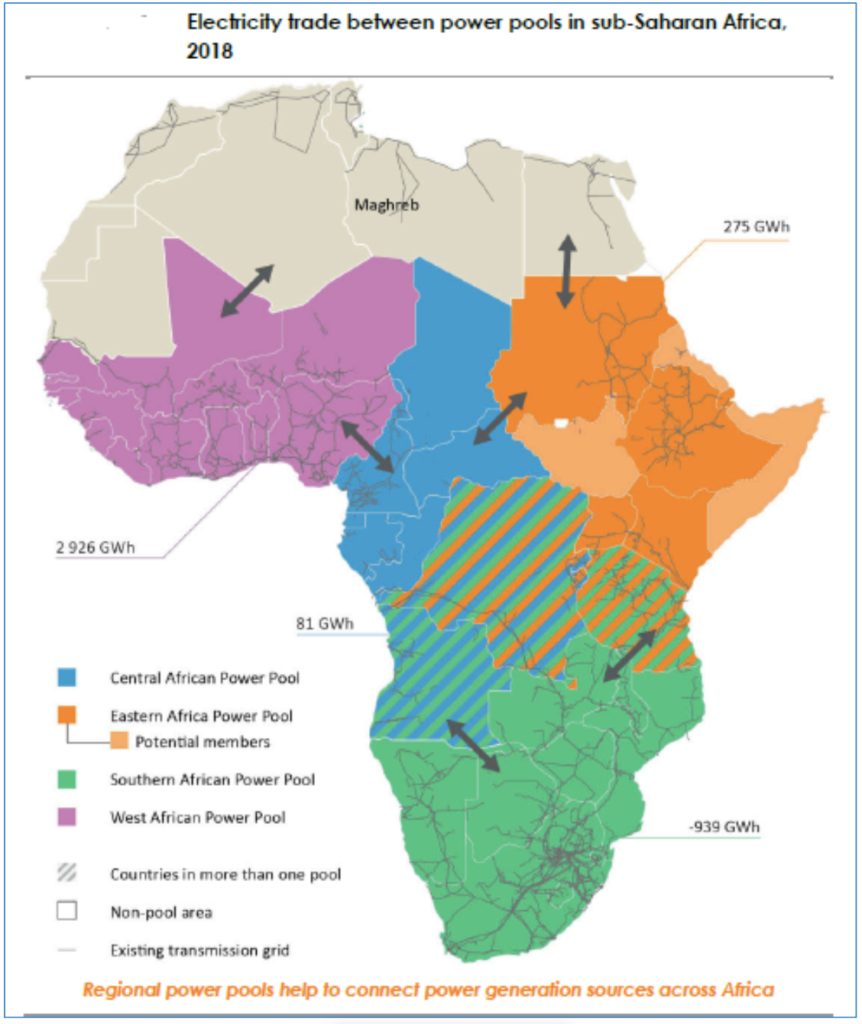

Enhanced network interconnectivity in the form of power pools and network loss reduction top the list.

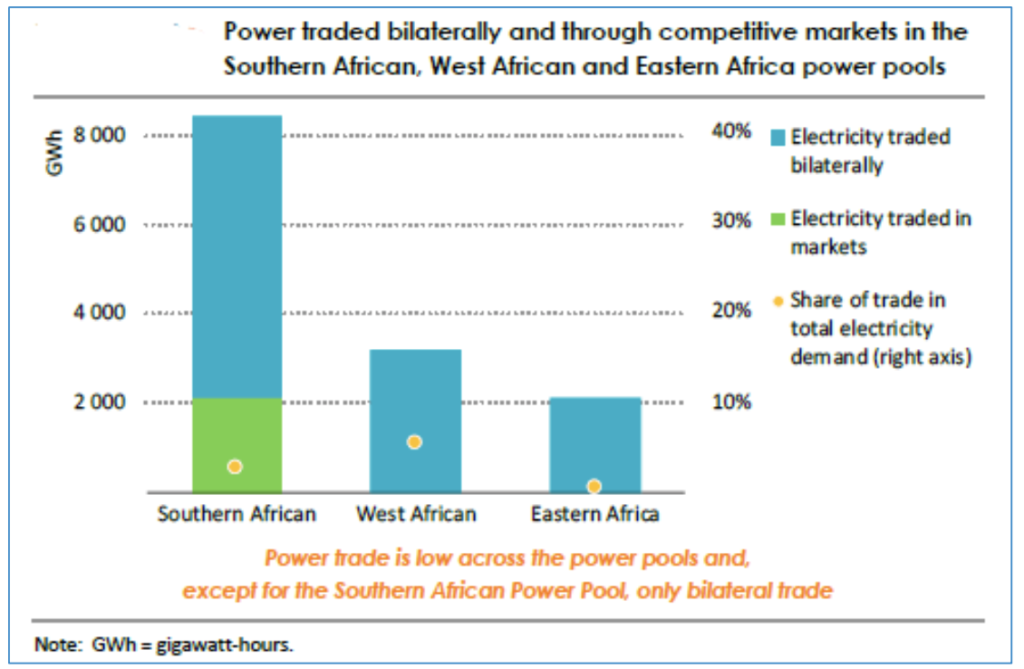

Unfortunately, electricity network interconnectivity across the continent has largely been a paper tiger until now. While there are various established power pool agreements available, a lack of transmission lines and political will results in very limited actual energy trade being carried out, as illustrated in the following two charts.

One major lesson from transforming existing fossil fuel power generation in Europe or, as will be the case for most of Africa, constructing new renewable capacity, is the need for proper interconnectivity and efficient regional electricity markets. This is fundamental to ensure the most efficient use of green technologies like wind or concentrated solar power whose efficiency largely depends on choosing optimal locations. The AfCFTA’s efficient implementation will be a crucial tool to achieve efficient regional energy markets, as will the construction of long-distance power lines along with the required set of sub-stations.

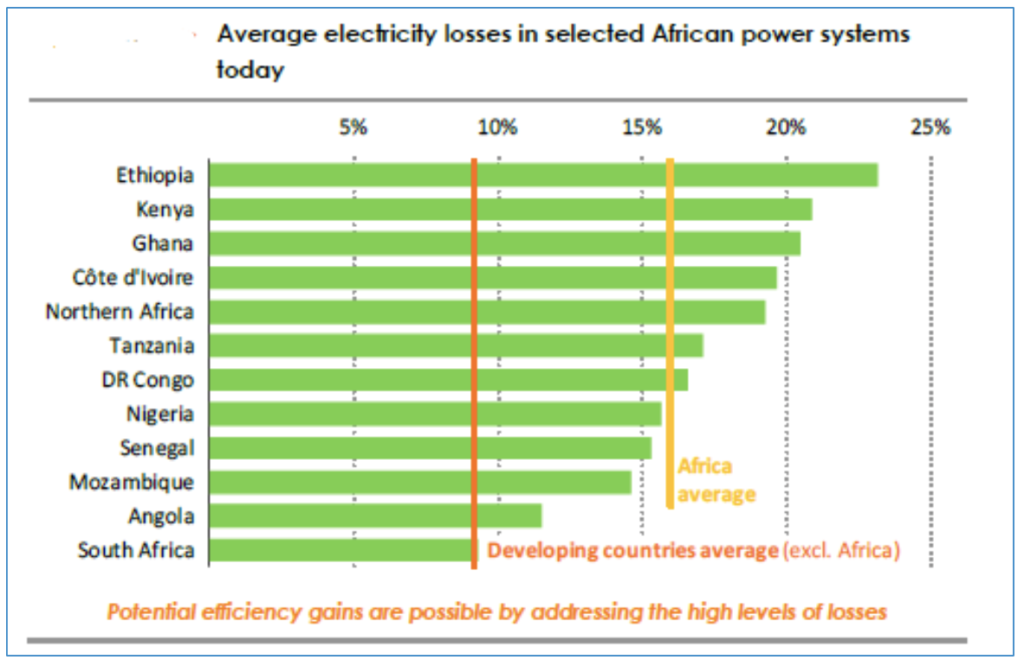

The other major tool, loss reduction is equally important. Power losses in almost all African regions are disproportionally high and exceed the global average of 8.3% significantly as indicated in the following chart. Enhanced enforcement procedures to reduce theft, but most importantly better run state-owned utility companies are another key element. More competition would obviously help in a number of cases, but this level of market liberalization often lacks political will and regulatory frameworks.

Conclusion

Africa’s energy transition is multifaceted. Simply tapping the vast green energy resources would be a blindsided approach. For investors in the energy sector, private and public alike, it’s key to take the bigger picture into account. This needs to involve a measured approach using all available resources and significantly enhance network and interconnectivity efficiencies.

Otherwise, Africa risks remaining stuck between a rock and a hard place, and to lose sight of the ultimate goal: reducing (energy) poverty.