Earlier this month, RentCafe reported their analysis of IPUMS data indicating Millennials’ landmark transition from majority renters to majority homeowners in the United States in 2022. According to RentCafe’s commentary, the average first-time Millennial homebuyer in 2022 was 34 years of age, two years older than Generation X and a year older than Baby Boomers were when they crossed the majority homeowner chasm. Given the longer period Millennials (and Generation Z) are spending at university (and therefore out of the workforce in early adulthood), the slight jump in average age of first-time homebuyers doesn’t seem too problematic, does it?

The 2021 Australian census offers some additional flavour to the education argument. In an October 2022 commentary, the Australian Bureau of Statistics defined Millennials of the 2021 census as 25-to-39-year-olds. The proportion of them with a bachelor degree or higher qualification is several times greater than Baby Boomers at the same age. You might think that a higher education among Millennials would be associated with comparatively higher income (and presumably higher rates of homeownership), but not if a bachelor’s degree is the “new normal” and no longer differentiates a job candidate. In the 2021 Australian census, 54.6 percent of Millennials were associated with home ownership. This contrasts with 62.1 percent of Generation X and 65.8 percent of Baby Boomers at the same age (in 2006 and 1991 respectively).

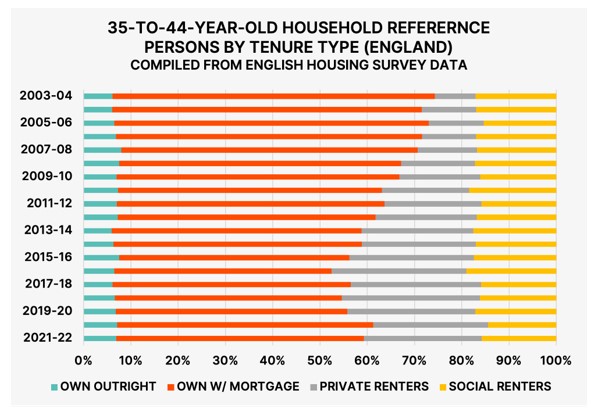

In the UK, the 2021-22 English Housing Survey indicated that 41.4 percent of households with a 25-to-34-year-old “reference person” were owner occupied. For the next age group (35-to-44-year-olds), we see a big jump in home ownership to 59.3 percent. Nevertheless, England’s 35-to-44-year-olds of today have a notably lower rate of owner occupation than those of two decades ago, when owner occupation for this age range was 74.3 percent (see chart below).

The rise of Generation Rent

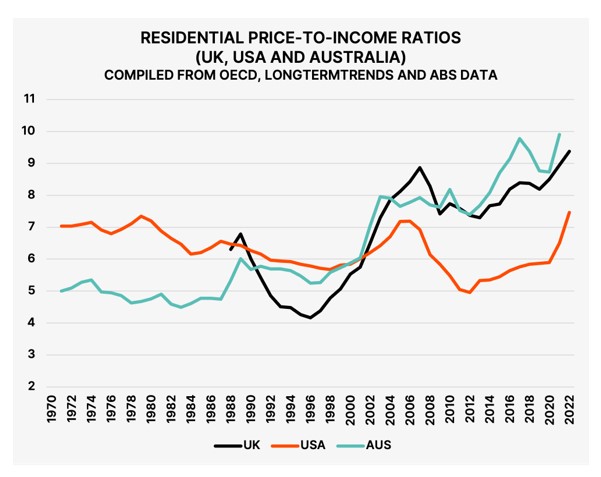

Aside from entering the full-time workforce at a later age, a number of issues have been flagged as causes of Generation Rent’s emergence. These include a growing gap between household incomes and home prices (price-to-income ratios—see chart below); spending habits; urbanisation; treatment of housing as an investable asset; undersupply; and more recently, the cost of living crisis. When it comes to price-to-income ratios, an aggressive upswing in some developed economies over recent decades has been associated with financial liberalisation and what is referred to as “The Great Moderation” which, until recently, saw progressive declines in interest rates.

Housing affordability initiatives

In 1980, England and Wales introduced the Right to Buy scheme in order to make homeownership a reality for social housing tenants. In 1981, the scheme experienced its peak, with over 200,000 dwellings transferred that year. In 1984, the UK Government offered maximum discounts of 60 percent for houses and 70 percent for flats—facilitating social mobility for those who got onboard at the right time. There are mixed perspectives of the efficacy of this scheme—including one that it was the fuel for a “40-year housing crisis” by relegating renters to the underserved and undersupplied private rental sector. Down under, facilitating access to the housing ladder has been largely focused on first-time homebuyer initiatives. Early examples include the post-WW1 War Service Homes Act (1918), but the First Home Owners Grant (FHOG) of the year 2000 will be a more familiar framework for today’s first-time homebuyers. It was initially intended to mitigate the effects of the newly introduced Goods and Services Tax (GST). Australia is also host to some of the most favourable tax conditions for direct residential property investors, which can serve as an alternative means of getting a foot on the housing ladder for “rentvestors”. Negative gearing tax incentives served as a repeated point of contention over successive federal election cycles, leading the Australian Labor Party to abandon their policy of dismantling it. In recent years, with claims that Baby Boomers are hoarding their nations’ wealth, the “Bank of Mum and Dad” has become the vehicle for partial intergenerational wealth transfers for the more fortunate Millennials. In the United States, LendingTree data indicates that 59 percent of Millennials are receiving help for their down payment.

The role of technology

Receiving financial help with homebuying can be messy, whether the help is from family, friends or other acquaintances. Knowing this, UK-based Generation Home created a solution which aims to mitigate the complexities of relationships and money. Peer-to-peer and crowdsourced lending was recently showcased by JustLend on the BBC’s Dragon’s Den series and CrowdProperty have demonstrated product-market fit for similar innovations in the development finance arenas of the UK and Australia.

Alternatively, digitally-enabled fractional equity platforms are increasingly offering democratised approaches to home ownership and real estate investment. These platforms have experienced mixed results, which Andrew Baum, Jimmy Jia and I recently chronicled in A piece of the action: innovations in fractional ownership and use of space. One platform has struggled to achieve scale by offering 1/10,000th shares in homes which are rented to long-term tenants. Rental income is distributed to investors monthly (net of a management fee). On the other hand, 1/8th fractions in second (holiday) homes have seen increased prevalence and adoption. WeWork’s Adam Neumann evidently views assisted homeownership as a significant area of opportunity, having announced his latest venture, Flow, earlier this year—a four-pillared business model facilitating co-ownership of homes with tenants. Without the advent of the “platform economy”, many of these business models would struggle to attain the requisite reach and scale.

Outlook

If you subscribe to the belief that housing in developed economies is overpriced, then you might also believe that innovations aimed at helping more people to participate in these overpriced assets fuels further competition (which consequently worsens the matter). One might even go further and argue Rousseau was right to question the very nature of land ownership, through the impostor who was first to enclose a piece of land and claim “this is mine”. These ponderances are easy from an armchair, but in reality, housing affordability innovators appear to be one of few groups taking meaningful action. Not only that, but by the established rules-of-the-game, land ownership is, and has been, fundamental to the distribution (or concentration) of power. Think of the controversies surrounding “terra nullius” in Australia, or the concerns around unequal distribution of home ownership on the basis of race in the United States. With no alternative silver bullet to solve the intergenerational inequities in real estate ownership, it is likely we’ll see increased adoption of digitally-enabled remedies by Generation Rent as the wealth transfer progresses.