The demise of high street retailing in the UK has been a subject of national concern for some time – and even mainstream TV and radio has covered the issue from a variety of angles. The very public failure of big-name brands such as Woolworths, Toys r Us, BHS and Debenhams heralds what is probably only the start of a saga which will have a continuing impact on the world of real estate. A large number of high street retailers are anticipating continued disruption from e-tailing and slower trade volumes. Consequently, they expect to pay much less rent over the next five years –either by giving up premises and/or renegotiating leases.

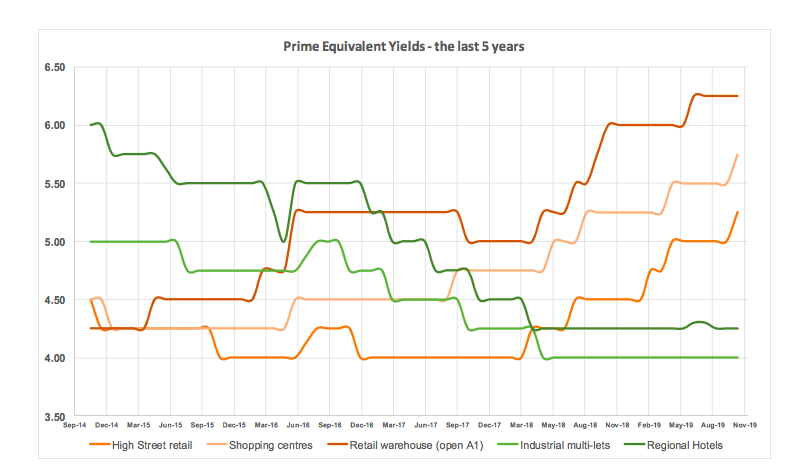

Despite long-standing concerns about the sustainability of the conventional retailing format in the face of digital disruption and the problems of ‘clone high streets’, it was only 4 years ago that this sector topped the investor charts. At the end of 2015, prime equivalent yields on high street retail were 4%. A few ‘ultra prime’ London units were even bought by overseas investors on a 2.5% yield in anticipation of significant rental growth.

All this serves to show how wrong the real estate investing world can be and how ‘group think’ can lead to potentially disastrous consequences – in what seems like a very short space of time. High Street retail yields have moved out to 5.25% now and will probably be nearer 6% before it’s all over. Retail warehouse yields have already climbed to 6.25% since the Halcyon days of 2014 when they were 200 bps lower.

This falling out of favour with investors is alone sufficient to account for a 32% fall in the capital value of retail warehouses. With retailers anticipating as much as a 30% fall in the rents they will pay in future and Savills reporting a 21% fall in retail rents in the year to September 2018, the combined effect, within a few short years, could amount to retail units halving in value.

So, if yesterday’s ‘blue-chip‘ covenant can fast become today’s difficult-to-let, boarded-up shop front, have we been measuring risk the wrong way?

I would suggest that the answer is a resounding ‘yes’. Not only have we over-valued conventional asset classes (because our peer groups continue to trade them) but we have also been under-valuing ‘non-institutional’, niche and unconventional asset classes for a long time. We have set more store in ‘not underperforming’ rather than looking forward for change and new areas of growth. Furthermore, performance is based on a set of backward-looking, annual metrics generated by a small group of near-identical investing institutions.

Real estate is an asset. I was always taught that an asset is something that puts money in your pocket but the property world’s obsession with estimated rental values (ERVs) rather than net cashflows and with gross cap rates rather than net effective yields seems to me to have obscured this fundamental of investing over the last 5 or 6 decades. Investors have become lazy as first the inflation of the 1960s, 70s and 80s provided them with rising asset values and then falling interest rates, or yield shift, in the 1990s and first two decades of the 21stcentury has done the same. Driving uplift through rental growth by actively adding value to places, people and economies became a lost art.

But the same plight experienced by retail property investors will be experienced by many more in other sectors who have been over-reliant on ‘blue-chip’ covenants, upward-only rent reviews, full repairing and insuring leases and all the other paraphernalia of the small, closed world of RE asset trading.

The good news is

Source: Savills Research

Traditionally, these types of asset have made direct property investors nervous. They involve a certain amount of reputational risk and require assessment of management quality and capabilities which goes beyond conventional building appraisal. These qualities, in my view, make ‘alternatives’ safer assets in the 21stcentury than the conventional ‘core’ assets of yesteryear.

This is because a wide variety of changes: digital, social, demographic, financial, environmental are making a tsunami of real estate disruption. The challenges experienced by the retail industry are just ripples on the shore of what is to come. A failure to recognise the extent and nature of these combined new risks is a significant risk to the real estate industry. The ability to manage disruption is what will de-risk the sector. Operational real estate offers greater capability in this regard than conventional core assets so, it makes complete sense that a large number of investors have turned to ‘alternatives’. This is not just a desperate late cycle search for yield but it does beg the question: what is the right yield?

In a world where interest rates have bottomed out and there is no more inflationary or yield-shift asset growth to expect, the main, the only driver of capital growth is rental growth. The value of a building in a low-growth environment can only be based on its real-world net income stream (and reasonable expectations for the future thereof).

My anticipation is that the value of future global investment trading will be based on the capability of buildings and their management teams to deliver net income streams. No wonder there is a growing conversation of ‘Real estate as a service’ and an increasing focus on the fundamentals of real estate value over the lifetime of buildings and neighbourhoods. There are also signs that the rate at which genuine, net income streams are capitalised is increasingly converging between sectors and at a global level. Risk will, in future, be measured as the capability of both a building and its management to adapt to new and changing occupier needs rather than conform to old-fashioned 20thcentury planning use classes and investor asset classes. There will be no alternative to Alternatives for the successful 21stcentury investor.