The share of real estate in pension portfolios has been increasing over time. The rationale for this increased allocation has often been the investors’ desire for stable returns, which has translated in a sustained interest for multi-family properties. While much research has documented the role of real estate in diversifying a mixed-asset portfolio, focusing on diversification benefits only is not sufficient as the primary objective of pension funds is to meet their future liabilities. Though some studies that analyse the benefits of real estate in an asset-liability management context exist, they typically rely on data that cover two or three decades only. Hence, there is a lack of evidence on whether real estate is useful in a pension portfolio when other economic environments are considered. Such analysis requires the use of much longer returns time series, which seldom exist for real estate. In a recent paper (“The role of multi-family properties in hedging pension liability risk: long-run evidence”), we intended to fill this gap and provide for a better understanding of the benefits through time of holding income-producing residential real estate in a pension fund portfolio.

Our study takes advantage of a unique dataset for Sweden spanning 145 years to investigate the role of multi-family properties in hedging the main component of pension liabilities; namely wage growth. For these investors, a potential benefit of holding multi-family properties is that residential rents should be closely related to wage inflation as higher wages permit households to afford higher rents. All else being equal, higher rent growth will positively impact upon both real estate income and capital returns. This is a desirable feature for an asset class in a pension portfolio, as a positive correlation between assets and liabilities reduces liability settlement risk.

To investigate the impact of adding real estate to a pension portfolio, we assess whether residential real estate generates incremental, risk-adjusted excess returns. We assess the difference between the out-of-sample performance of portfolios containing real estate and that of portfolios containing financial assets only. Portfolios of financial assets are constructed using four different allocation strategies: a fixed allocation of 60% to stocks, 35% to bonds, and 5% to bills; a method that maximises the ratio between portfolio return and the standard deviation of returns; a minimum variance approach; and a risk parity method. For each portfolio allocation strategy, we consider the benefits which result from adding a fixed allocation of 20% to real estate. The out-of-sample benefits are assessed over rolling 30-year periods, with the portfolio allocations rebalanced to target weights every three years.

The Swedish case is appealing for multiple reasons. Firstly, the availability of long-run time series for apartment buildings rather than housing makes it possible to examine real estate’s role in a portfolio in various environments. Secondly, Sweden being an open economy, its economy should be integrated with that of other developed countries. Finally, the Swedish residential rental market is a hybrid system between strict regulation and free market. This feature is observed in many developed countries, albeit in different shades. Both the commonalities in economic patterns and in rental market structures between Sweden and other developed countries indicate that the conclusions of this study should apply to other countries.

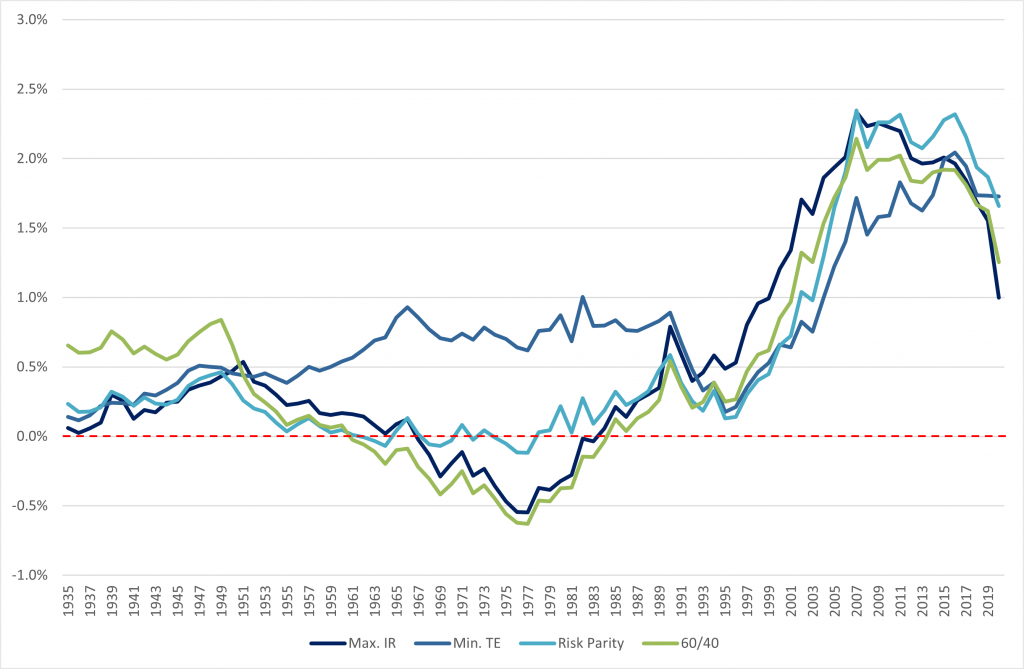

Let us consider first how the portfolio return changes when real estate is added to the portfolio while risk is held constant (Figure 1). Overall, the expected benefits from holding real estate are in a range from 39 to 78 bp per annum. The minimum tracking error strategy consistently yields a positive risk-adjusted excess return when adding real estate to a portfolio. The average risk-adjusted excess return is 77 bp, but this benefit varies over time between 12 and 204 bp. The risk parity strategy has the second highest average excess return at 53 bp. This strategy, however, has a significantly lower excess return than the minimum tracking error strategy from the 1950s to the 1980s. Considering now the riskier strategies, the average excess return is 39 bp for both the maximum information ratio and 60/40 strategies. However, out of the 86 periods, the excess return was negative during a quarter of the periods, suggesting that caution should be exercised when including real estate in a portfolio that targets riskier allocations. For these riskier strategies, the worst period saw a negative return of more than 50 bp, which translates into a negative return exceeding 15% over the 30-year period.

It is also interesting to note that, for all allocation strategies, excess returns increased substantially after the banking crisis of the early ‘90s. This effect is mainly attributable to the important compression in capitalisation rates (−450 bps) that arose after 1995, when cap rates plunged for the first time under the 3% mark. These large excess returns demonstrate the importance of understanding the real estate return dynamics in various economic environments, as the conclusions that would be drawn from looking at only the past two or three decades of data differ substantially from those for earlier time periods.

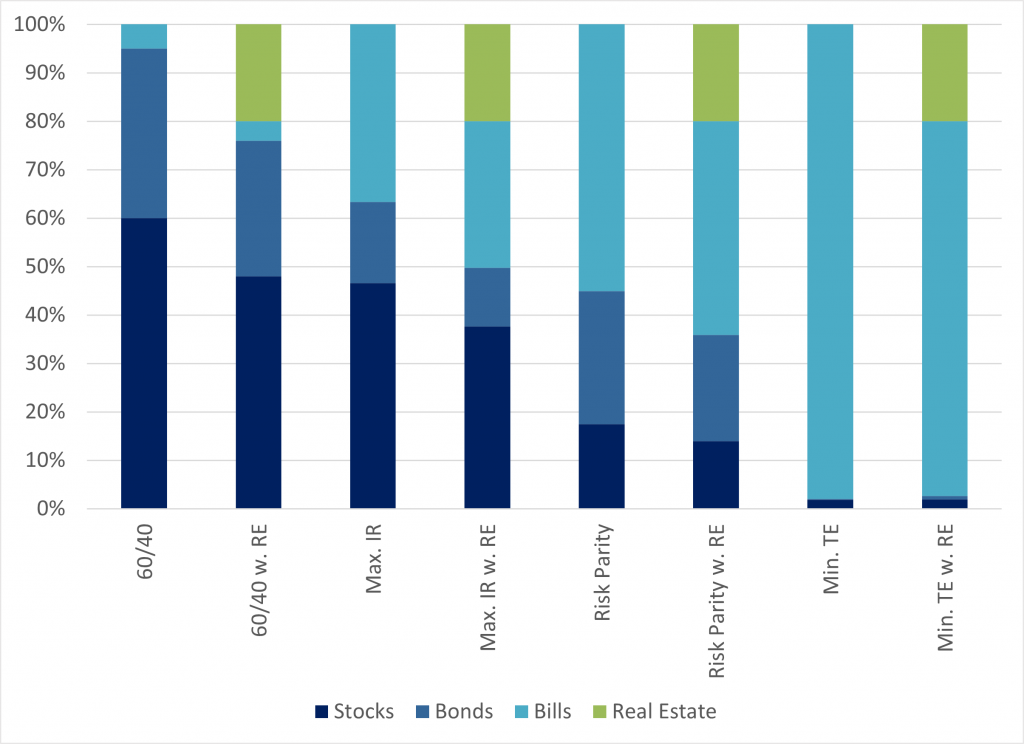

To understand why low-risk strategies benefit more from the inclusion of real estate than high-risk strategies, it is important to apprehend how portfolio compositions change when the asset class is added (Figure 2). For the minimum tracking error strategy, in which bills dominate the allocations, real estate mainly replaces bills. As real estate has a tracking error in line with that of bills, but a higher return in excess of wage growth, the portfolio containing real estate maintains its ability to track wages while improving the excess return. This leads to positive risk-adjusted excess returns. The same reasoning applies to the risk parity strategy, albeit the substitution effect and performance improvement are more muted given that the initial allocation is more balanced across asset classes. In the case of the high-risk strategies, the initial portfolios are heavily allocated to stocks and bonds. As a result, real estate substitutes for stocks and, to a lesser extent, bonds and bills. Although the information ratio of real estate is higher than that of bonds and bills, it is only marginally higher than that of stocks, and hence adding real estate results in a moderate risk-adjusted excess return. Overall, this means that the benefits provided by adding real estate to a mixed-asset portfolio will crucially depend on the existing portfolio composition.