There’s no shortage of money, and no surplus of people . . . if anything, there’s a shortage of good productive things to invest in, and it’s unclear what rates have to do with it.

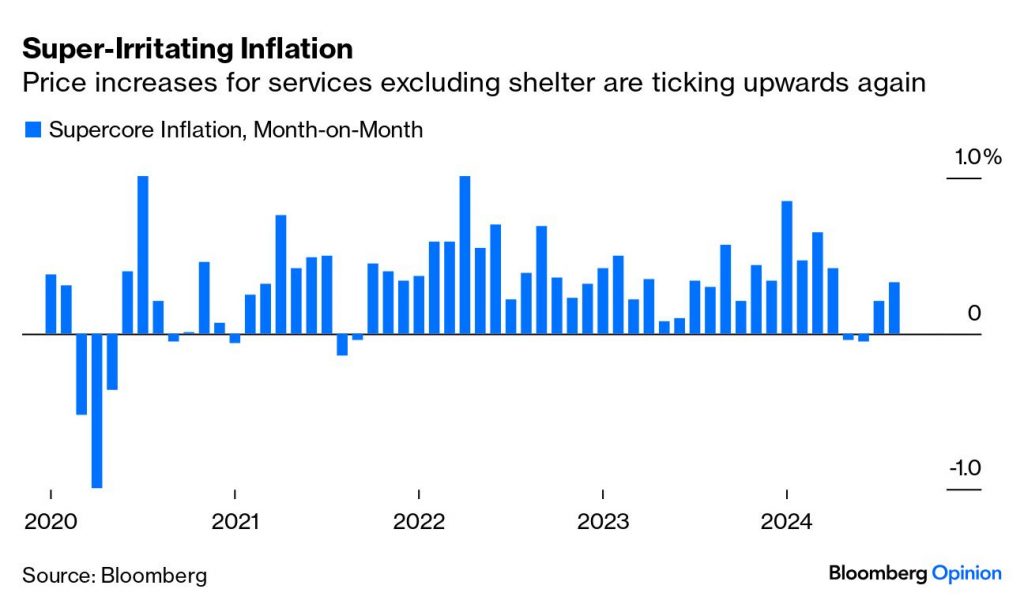

- mind the super core

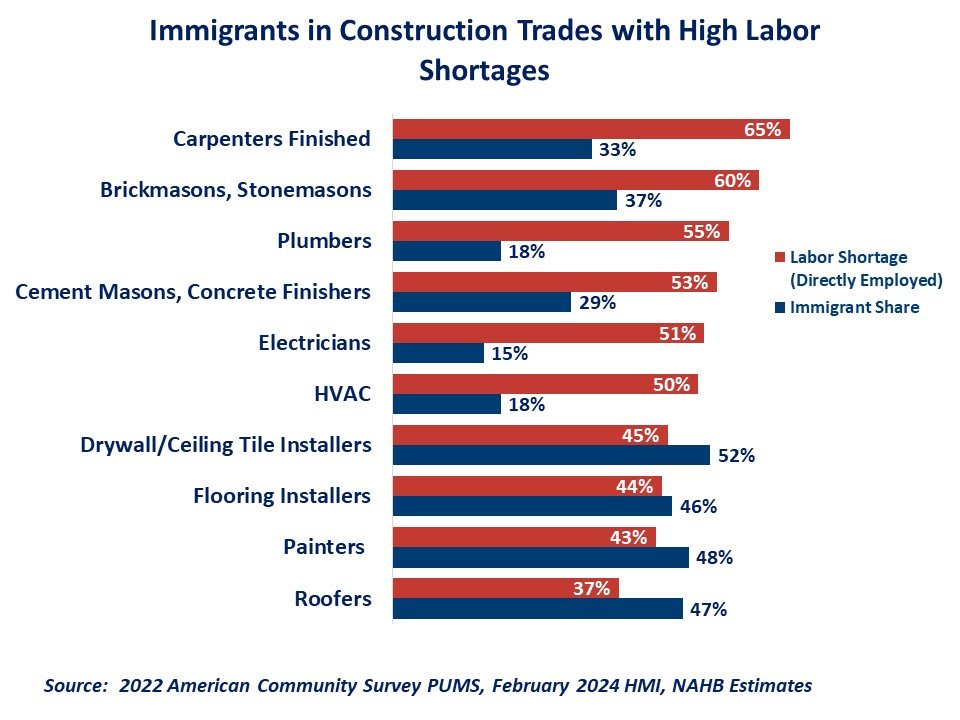

- people shortages are still out there, particularly in capital intensive sectors (like construction)

- no money shortage and no people surplus, so cheaper money seems like a solution in search of a problem

Lowering rates accomplishes what exactly?

Random Walk is at a conference, so I will be very brief (and without all the usual backlinking)

Fed-cut day is nigh, and the question is not “if” but “how much?” Random Walk will make no effort to answer that question because you might as well flip a coin.

The more interesting question is what is left to expand?

Mind the super core

As a reminder, basically the only bit of inflation that remains persistently above trend is services inflation, but really “core” services, i.e. the stuff most directly tied to people-costs.

Mom super-core inflation is trending upwards again.

At 0.02% mom, that’s a pretty livable growth rate, but the concern, of course, is reacceleration.

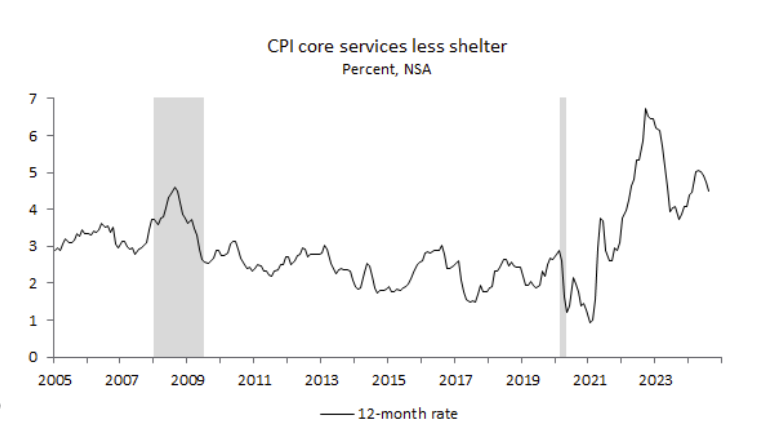

On an annualized basis, “super core” services look like this:

Super core inflation has been trending back to normal recently, but at just under 5%, it’s still substantially higher than before.

The reason that super core inflation is persistently high (and persistently concerning) is that it’s driven by a secular phenomenon: an aging population and shrinking labor force. This is a long-running theme for Random Walk, and while it feels good to be right, it doesn’t really address the question.

No shortage of money, and no surplus of people . . . so rate cuts help how?

So, let’s say that the Fed lowers rates to reverse the “softening” in the labor market, what then? The ratio of job openings to workers blows out wide again? Who exactly is going to fill those roles?

Oh look, with lower rates, we’re going to unleash a whole new wave of construction and manufacturing employment . . . where we’re already chronically short workers (with or without immigrants):

Most of the major construction trades report some or serious labor shortages (and have a relatively small share of foreign born work).

‘More construction’ just seems like a solution that brings a fresh set of problems (or a reprise of the problems we just had).

As a reminder, unemployment has been driven by new- and recent-entrants. Those people still matter—and of course, it could always get worse for everyone else—but it’s not like there is a lot of slack labor inventory out there, just waiting for a call.

Conversely, there is no shortage of money out there. Public equities and money market funds are achieving all-time highs.

So if there’s no shortage of money, and no shortage of things to do, then what exactly do rate cuts hope to achieve?

The problem, if anything, is a lack of good productive things to invest in. We need to be figuring out ways to do more with with less—which we surely have the ability to do, if we set our minds to it (and on certain fronts, we already are)—and not stimulate demand for workers that we don’t actually have.

Rates just seem like a sideshow at the moment, unless you’re in one on of those asset classes that benefits from money sloshing from one part of the capital markets to another. But in the big scheme of things, what problem do lower interest rates solve for?

Right? What am I missing here?

“Rates go up, rates go down” just seems like an old playbook for conditions that no longer apply.

This article was originally published in the Random Walkand is republished here with permission.