Tax increases are bad fiscal policy, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that they are politically unpopular.

Indeed, many voices in the establishment press are citing favourable polling data in hopes of creating an aura of inevitably for President Biden’s proposed tax hikes.

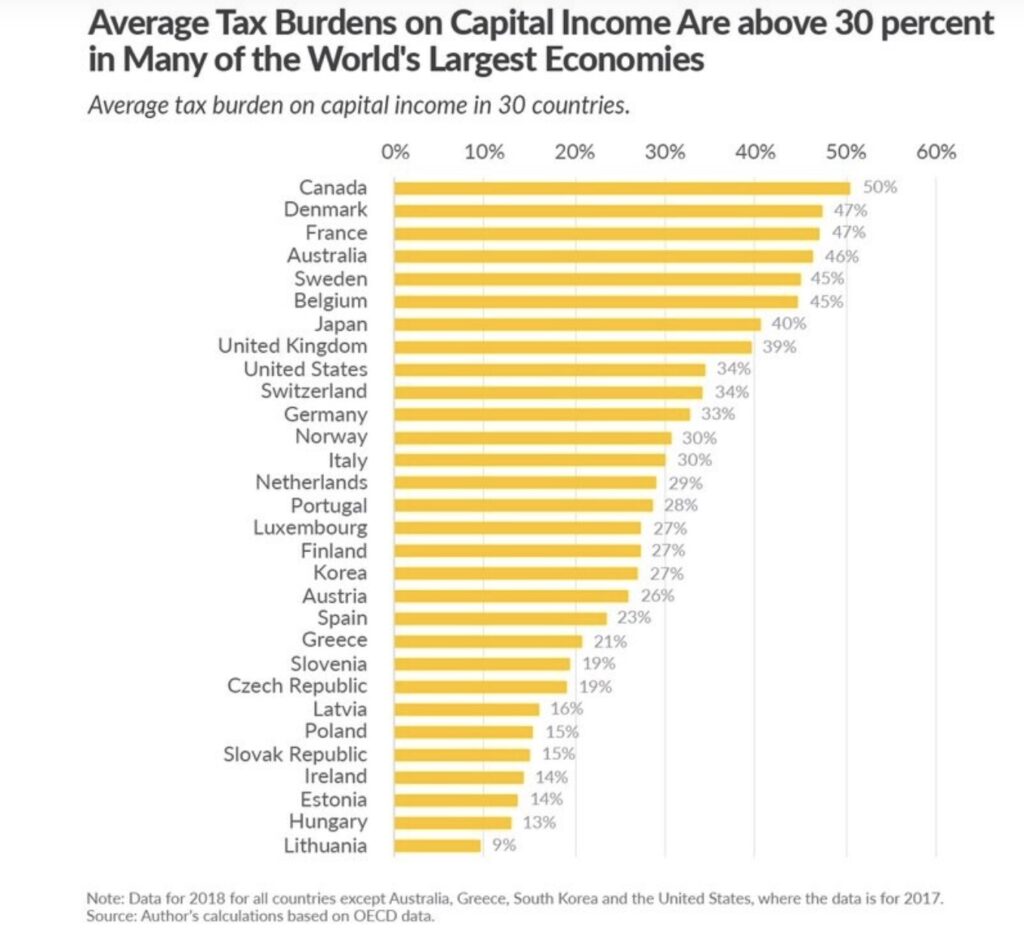

That’s a very worrisome prospect. If Biden succeeds, the United States could wind up toppling Canada for the dubious honour of having the world’s highest tax burden on saving and investment.

That would be bad news for American workers.

But are Biden’s media cheerleaders correct? Are tax increases popular?

According to a new scholarly working paper from the Federal Reserve (authored by Andrew C Chang, Linda R Cohen, Amihai Glazer and Urbashee Paul), the answer is no. – at least if we judge politicians by what they do in election years. Here’s part of the study’s abstract.

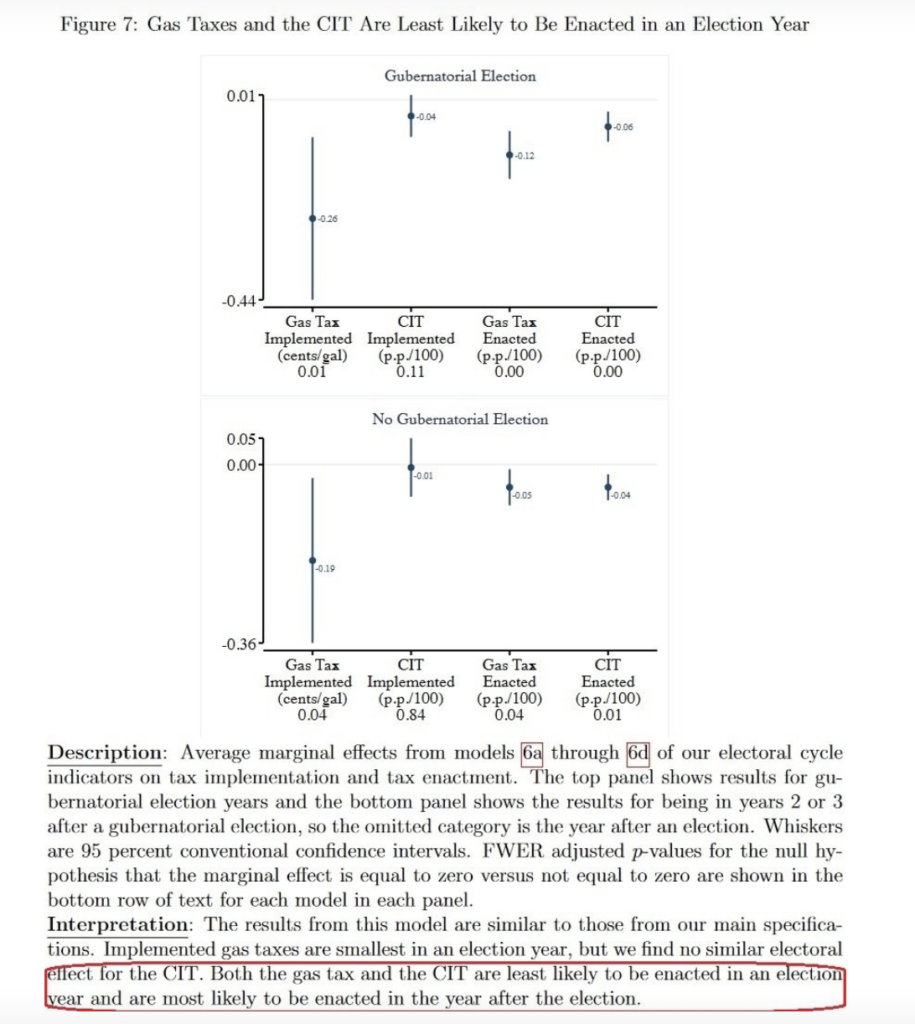

We use new annual data on gasoline taxes and corporate income taxes from U.S. states to analyze whether politicians avoid tax increases in election years. These data contain 3 useful attributes: (1) when state politicians enact tax laws, (2) when state politicians implement tax laws on consumers and firms, and (3) the size of tax changes. Using a pre-analysis research plan that includes regressions of tax rate changes and tax enactment years on time-to-gubernatorial election year indicators, we find that elections decrease the probability of politicians enacting increases in taxes and reduce the size of implemented tax changes relative to non-election years. We find some evidence that politicians are most likely to enact tax increases right after an election. These election effects are stronger for gasoline taxes than for corporate income taxes and depend on no other political, demographic, or macroeconomic conditions.

For wonkier readers, figure 7 has some of the major results of their statistical analysis. I’ve highlighted (in red) the most important conclusion of the research.

For regular readers, the main takeaway is that politicians almost always want more tax revenue. That’s what gives them the ability to distribute goodies and buy votes.

But notwithstanding their never-ending hunger to grab more money, they are very likely to reject tax increases in election years. They even reject higher corporate taxes, which are supposed to be popular (at least according to some in the establishment media). Yet if tax increases were politically popular, we should see the opposite result.

I’ll close with the somewhat depressing observation that these results do not imply that voters want libertarian policy. It’s probably more accurate to say that people want goodies from the government, but they don’t want to pay for them. Politicians simply respond to those preferences (which brings to mind Garett Jones’s hypothesis that we have too much democracy).

Which is how Greece became a basket case, and which is why Italy is in the process of becoming a basket case and it’s why the United States may not be that far behind (with states such as Illinois serving as early warning signs).

The above-cited research should be a reminder of why a no-tax-hike pledge is important. Voters seem to be on the right side on the big-picture question of “Should taxes be higher?”, but if they think tax increases are going to happen, it’s quite likely that they will support the most economically damaging types of class-warfare levies.

This article originally appeared in The American Institute for Economic Research and is reprinted here by permission.