When the annual PERE/Sousou Partners 2021 compensation survey appeared in my LinkedIn feed earlier this year, I couldn’t help but notice the somber headline: Private real estate firms cancel bonuses during the pandemic!

Briefly considering an impromptu appeal to lawmakers in Brussels and Washington to lend a helping hand, I soon realised that only five out of more than 900 survey participants suffered a zero bonus round. Heaving a sigh of relief, curiosity took over and I kept wondering what those five outliers had in mind when slashing bonuses.

Was it simply the risk of taking the good ol’ “greed is good” a step too far in a situation where the fund’s very survival (along with the LP’s cash) was at risk or was there more? The idea that those fund managers actually considered what the investment partnership model is all about may not be too far-fetched.

Partnership structures have been around for a while. From theqirad (modern day’s mudarabah) in Islamic finance, the Jewish ’isqaor the Roman societas, all the way to the commenda in medieval Italy, market participants have a long history of sharing responsibilities and rewards. All these early partnership models have in common is the fact that they combine skill sets and capital in order to build a profitable business.

Why is this of relevance today?

Modern PE fund vehicles represent pools of capital set up with the general idea of mitigating risks through diversification. In addition, the core partnership principle remains intact: aiming for adequate and consistent risk, and profit allocation and interest alignment among the partners involved.

However, various developments within the PE industry over the past few decades have raised eyebrows and forced investors to question whether the original partnership idea is still alive. As part of the discussion, an array of agency issues has surfaced.

Discussion topics range from limited transparency, the size of management fees and performance measurement, all the way to risk governance issues, including carry provisions like clawbacks.

Driven by the LP’s experience of “holding the short end of the stick”when fund vehicles are underperforming, eg, during the 2007-2008 GFC, the latter has been a hot topic ever since.

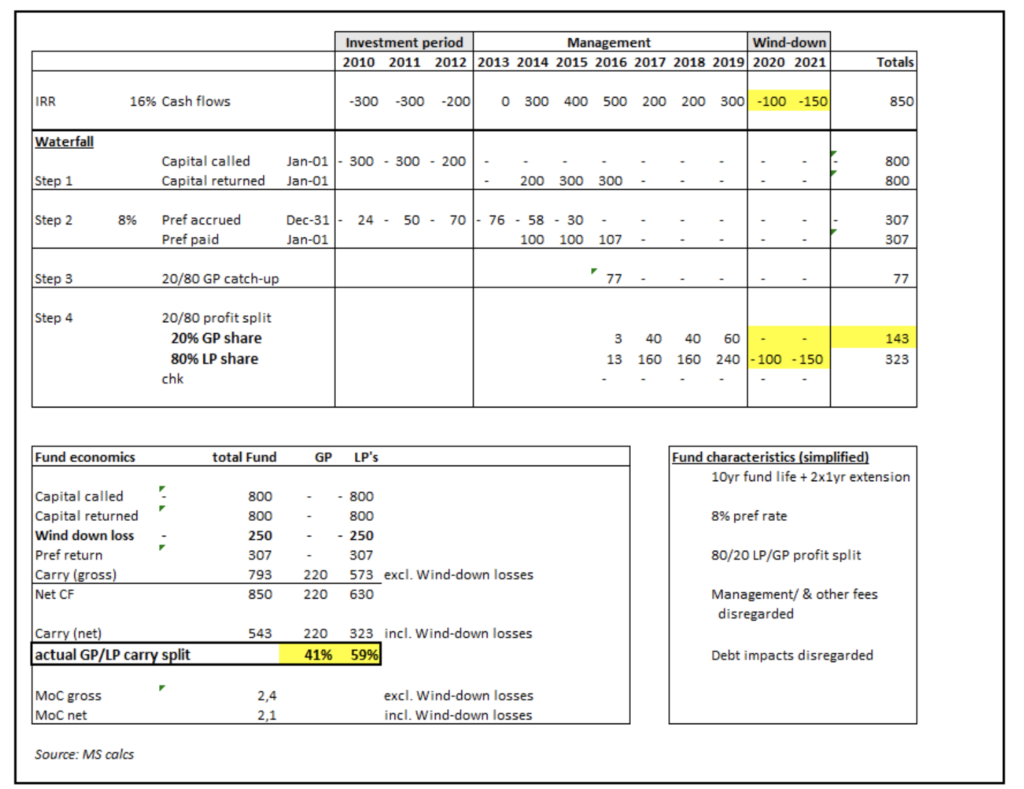

So, let’s consider a simplified PE waterfall scenario and see why clawback provisions are important to prevent incentive distortions.

My illustrative and simplified example shows a diversified PE RE fund raised in the GFC’s aftermath. All went well, except for two retail assets which faced increasing pressure due to the shift to e-commerce. In late 2019, the GP decided to use the 2 x 1 year fund extension option in the hope of turning the two assets around with a revised leasing strategy. Then covid came along, wiping out the bottom line for both assets with little hope of recovery. The GP decided to sell, incurring losses of 250 units to be entirely borne by the LPs, since the LPA did not entail any carry clawback provisions.

Without any GP pari passu loss participation, the funds’ profit distribution structure subsequently became significantly distorted. What once had been stipulated to be an 80/20 profit-sharing arrangement suddenly ended up as a 59/41 split.

So, how’s the market reacting?

The general PE discussion is in full swing, ranging from the press (FT: Private equity fees have become a rentier’s bonanza) to the institutional investor community. The latter group’s recent public outcry, like the influential AFT’s Lifting the Curtain on Private Equity, is obviously the more concerning one since it may affect the willingness to participate in future fund raises. The power of similar reports within the public pension fund community had been demonstrated by allocation adjustments following AFT’s damning 2015 report on hedge funds: All That Glitters is not Gold.

How does the PE industry address the issue?

Slow and with subdued enthusiasm describes it rather well.

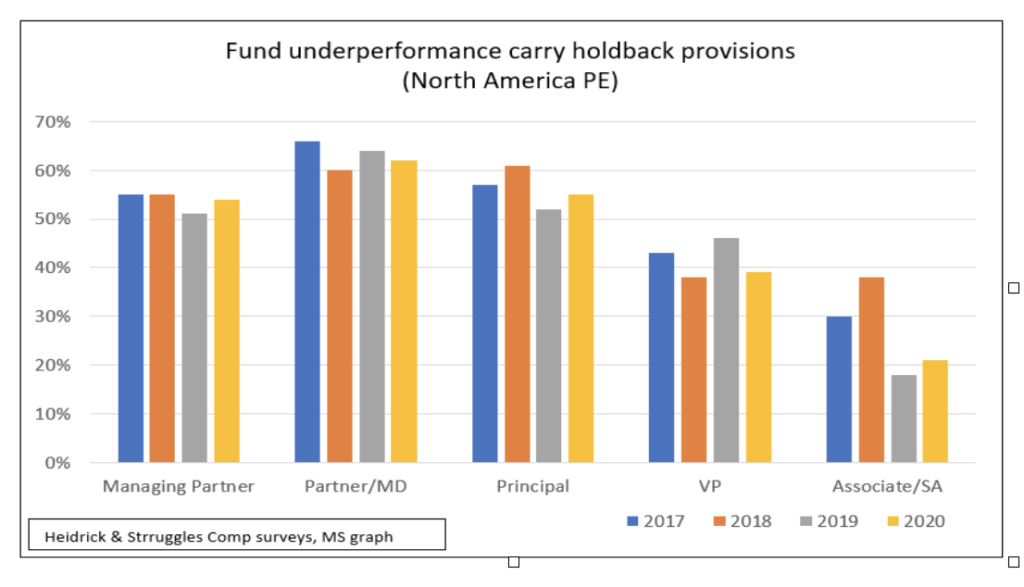

Judging from Heidrick & Struggles’ North American PE comp survey data, carry holdback provisions appear now to be relatively widespread among senior ranks.

However, little progress has been made in the recent past, which is likely to be a reflection of the liquidity-induced power shift towards GPs. Compared to public equity markets where, according to ISS, some 93% of S&P 500 firms now feature clawback provisions as part of senior management’s comp arrangements, the PE industry has room for improvement.

What about capital allocators?

Looking at engagement trends in public equity markets, especially since the GFC, many more shareholder letters are being sent to companies by large institutional investors like CalPERS/CalSTERS, pushing for governance reforms including clawback provisions.

I expect a similar trend to gain momentum in private capital markets going forward.

In addition, boards and management of larger institutional investors show an increasing willingness to invest in internal investment underwriting, and asset management capabilities and platforms. These certainly help to build a credible threat of deploying capital directly vs allocating it to indirect fund investment mandates. The ability to build in-house institutional knowledge and, in the age of PropTech, gain insights through data generated across the property portfolio are added benefits.

What’s in it for the partners?

For LPs the obvious answer is: better risk and interest alignment and, as a result, downside protection.

For GPs adopting clawbacks it’s about sending a strong message to their investor base: “We’re partners in a business. When we are going through rough times we’re willing to share the pain as we do in the upside if and when the tide turns.”

No doubt this will be well remembered by LPs when the next fund is being raised and private market capital may not be as plentiful as in the past.

Last but not least, there is also encouraging research data following the REIT industry’s adoption of compensation clawbacks starting in 1993, culminating in the following statement: “The presence of a clawback is associated with both enhanced market returns and operating cash flows.”

If nothing else, that’s an outcome likely to be agreeable to everyone.