BAE Systems is an obvious choice for dividend investors.That’s because:

(1) BAE

(2) BAE has a long track record of dividend growth, with the dividend going from 9.2p in 2003 to 22.2p in its 2018 results.

(3) BAE has a decent dividend yield of 4.7% at its current price of 458p.

However, BAE also has a few features which make it less attractive than it might at first appear.

BAE’s dividend growth is not matched by earnings or revenue growth

Long-term dividend growth is almost a requirement for attractive dividend-based investments, but dividend growth alone is not enough.

That’s because dividend payments must be covered by earnings, which are extracted from revenues, which come from customers paying for products or services, which are produced using the assets of the business (e.g. factories, warehouses and stock), which are paid for with shareholder and debt holder capital.

So if earnings, revenues and capital employedare not going up then any dividend growth will eventually hit a ceiling.

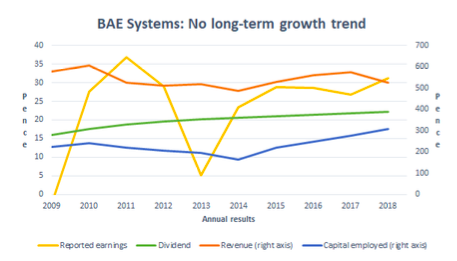

With that in mind, the previous chart shows several things:

(1) BAE’s revenues have gone essentially nowhere for a decade.

(2) BAE’s earnings also show no obvious growth trend.

(3) BAE’s capital base (i.e. capital employed) shrank following government cutbacks after the global financial crisis. This came about through a mixture of business writedowns, disposals and ‘rightsizings‘. After 2014 the company’s capital base has returned to growth, but this a relatively short period and has yet to drive consistent revenue growth.

(4) BAE’s dividend has continued to grow every year, but the rate of increase has slowed from more than 5% per year to less than 2% per year today.

This lack of consistent broad-based growth is not the end of the world and I wouldn’t rule out investing in BAE because of this alone. But averaged across capital employed, revenues and dividends, its growth has failed to match inflation over the last decade, and that has to be reflected in the purchase price.

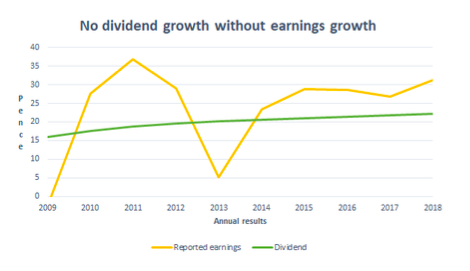

BAE’s dividend cover is wafer thin

An uncovered dividend is a classic sign of a dividend under threat, so having earnings that consistently cover the dividend is important.

In BAE’s case, its progressive dividend growth and lack of earnings growth has given the company an average dividend cover over the last ten years of just 1.2.

In other words, the company has paid out 85% of its earnings over the last ten years as a dividend, and that’s a problem for a couple of reasons:

(1) The margin of safety between earnings and the dividend is relatively thin, so any small but prolonged decline in earnings is likely to put the dividend under severe pressure.

(2) With just 15% of earnings being retained, BAE may find it hard to increase its investment in productive capital assets such as offices, factories and machinery (often called property, plant and equipment) in order to drive future growth.

This isn’t necessarily a disaster waiting to happen, but thin dividend coverage and the related squeeze on growth investment should also be reflected in the price.

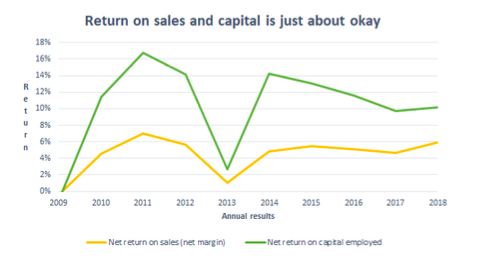

BAE’s profitability is just about acceptable

I have two rules relating to the returns a company makes:

(1) Only invest in companies that have a ten-year average net return on sales above 5%

(2) Only invest in companies that have a ten-year average net return on capital employed above 10%

The first rule looks at net return on salesbecause I want to measure the margin of safety between a company’s income and its expenses. For example:

Imagine a company with a net return on sales of 2%. This means it has expenses of 98p for every pound of revenues, so it has just 2p per pound to act as a buffer, or margin of safety, between income and expenses.

Any rise in expenses must immediately be passed onto the customer, otherwise the thin profit margin could disappear and turn profits into losses very quickly.

The same applies to a small decrease in the price customers are willing to pay for the company’s goods or services. Expenses would have to be cut rapidly, otherwise the wafer-thin profit margins would be wiped out in no time.

Some companies can cope with thin profit margins much more easily than others. These are typically companies that earn a relatively fixed percentage on the cost of goods or services sold, such as energy suppliers or product distributors. Even so, thin profit margins are generally not a good sign.

In BAE’s case, over the last decade it produced total net profits of £7.7 billion, which is a lot. However, it took total revenues of £177.8 billion to generate those profits, giving an average net return on sales of 4.3%. That’s below my 5% floor, which is enough to set off some mental alarms.

Somewhat more optimistically, its return on sales has averaged 5.2% over the last five years, but that is still barely above my minimum standard.

To generate those profits, which average out to £766m in each year, BAE employed capital from shareholders averaging £4 billion and capital from debt holders averaging £3.6 billion. So BAE’s average capital employed was £7.6 billion, and that capital produced average net profits of £766m, giving an average return on capital of 10.2%.

A return on capital employed of 10.2% is barely above my minimum standard of 10%, and by that measure BAE is a very average company.

Having said that, the company’s capital structure is clouded somewhat by two very large balance sheet items: £10 billion of acquired goodwill and a £4 billion pension deficit.

Acquired goodwill clouds the profitability picture

The acquired goodwill (which is the amount paid for an acquired company above and beyond its net tangible assets) was mostly added to the balance sheet between 1998 and 2008 when BAE spent upwards of £10 billion buying other companies.

Over the same period the company generated a total of £4.3 billion in net profit, so spending £10 billion on other companies was a very ‘enthusiastic’ way to run the business. It’s what I call an acquisition spree, in this case funded by debt holders (via an additional £2.5 billion of debt) and shareholders (via a 70% increase in the number of shares).

Acquired goodwill makes it harder to see what sort of return a company might get on any earnings which are invested directly (i.e. organically) into tangible assets such as property, plant and equipment. And that’s important because companies with strong competitive advantagescan typically earn above average rates of return on tangible assets.

For example:

Imagine a company with one factory which it built for £100 million. The company has strong competitive advantages and its factory produces profits of £40 million per year, giving a very high return on capital of 40%.

If another company then acquires that first company for £500 million, the acquirer will have a £100 million tangible asset on its balance sheet (representing the factory) and a £400 million intangible asset (the acquired goodwill).

The acquirer will still get £40 million of profits annually from this factory, but its return on capital employed is a far less attractive 8% (£40m per year from a £500m investment), purely because of the price it paid to buy the factory.

However, the return on tangible capital (i.e. excluding the intangible goodwill) is still 40%, and this gives a better indication of the company’s competitive advantages.

It is also a better guide to the return the acquirer might get if it used retained earnings from the first factory to build a second factory, assuming that factory was as profitable as the first.

That’s why it can be a good idea to look at net returns on tangible capital (which excludes any acquired intangible goodwill) as well as net return on capital.

In BAE’s case, if we adjust capital employed to remove the £10 billion of intangible assets and also add back in the £4 billion pension deficit (kindly assuming that it doesn’t exist) then BAE has produced an average net return on tangible capital employed of 53%, which is very good. This suggests the company has some strong competitive advantages.

However, the fact that BAE has grown to a large extent through acquisition suggests that there are few opportunities for significant organic (i.e. internally generated) growth. So while the company may in theory be able generate high returns by investing retained earnings into new tangible assets, in reality the company may have to acquire its way to growth.

If that’s true, future returns on capital will be determined as much by the price paid for acquisitions as it is by returns on organic investment into factories, machinery and so on. In which case, the standard return on capital (about 10% for BAE) is a reasonable estimate of the return investors can expect on any retained earnings.

In summary then, (1) BAE may have strong competitive advantages but (2) its opportunities for significant organic growth may be limited, so (3) it may be forced to grow primarily by acquisition.

Let’s turn to the other complicating factor: the company’s large pension deficit.

BAE’s financial obligations are on the high side

Companies with large and inflexible financial obligations can often find themselves in a lot of trouble very quickly. That’s why I have a couple of related rules:

(1) Only invest in defensive sector companies where total borrowings, including money ‘borrowed’ from any defined benefit pension funds (i.e. the pension deficit) are less than five-times the company’s ten-year average profits (which I call the Debt Ratio).

(2) Only invest in companies where total borrowings plus total pension liabilities (total liabilities, not just the deficit) are less than ten-times the company’s ten-year average profits (which I call the Pension Ratio).

The rules for calculating pension deficits are long and shrouded in mystery, and for a variety of reasons there is almost always a difference between a pension fund’s ‘accounting’ deficit and its ‘actuarial’ deficit.

In BAE’s case, it has a net retirement benefit obligation on its 2018 balance sheet of about £4 billion, while the results of its triennial actuarial valuation show a funding deficit of £2.1 billion.

Let’s be kind and assume £2.1 billion as our working figure. So BAE’s:

- ten-year average net profits come to £766 million per year

- total pension liabilities (the total liability, not just the deficit) are £23.7 billion

- net pension deficit is £2.1 billion

- total 2018 borrowings are £4.3 billion

- total borrowings plus money ‘borrowed’ from the pension fund (i.e. the pension deficit) equals £6.4 billion

Those figures give the following results:

- Debt Ratio:Borrowings plus pension deficit to 10yr average earnings = 8.3 (my limit is 5)

- Pension Ratio:Pension liabilities plus borrowings to 10yr average earnings = 36.5 (my limit is 10)

By these measures, BAE has a lot of debt (its borrowings alone are almost 6-times its average earnings). However, its the pension scheme which really puts the nail into the coffin for BAE as a potential investment, as far as I’m concerned.

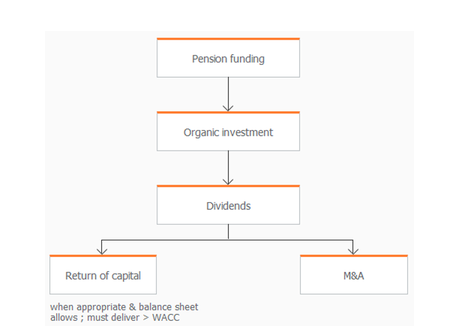

According to its annual report, BAE is currently paying some £200 million per year into the pension fund in order to reduce the deficit (in comparison, the dividend paid to shareholders is about £700m/yr). That level of deficit reduction is expected to continue until at least 2022, and the company has agreed that any future dividend increases must be matched by additional payments into the pension fund.

In fact, BAE’s stated first use of cashis to pay down the pension deficit, ahead of organic investment in productive assets, dividend payments to shareholders or acquisitions. The image below is taken from the company’s website:

In recent years BAE has entered into several insurance deals where longevity risk (i.e. the risk that pensioners live longer than expected) is effectively offloaded to an insurance company. For a fee, of course.

However, these longevity swaps(as they’re known) only cover a few billion out of the total £24 billion liability, so most of the longevity risk still sits with BAE and its shareholders.

These huge financial obligations, layered on top of the company’s low-growth track record, thin dividend cover and thin profit margins, are not the sort of features I look for in a long-term investment.

Nice dividend, shame about everything else

Despite BAE’s initially attractive dividend yield, at 458p the company’s shares currently sit at position 126 on my stock screen, out of about 200 consistent dividend payers from the FTSE All-Share.

That’s below the halfway point which implies, somewhat simplistically, that BAE is probably priced above fair value. In other words, the share price may be too high given the company’s growth, profitability and debt characteristics.

More importantly, because of the significant risks around the company’s thin profit margins, enthusiastic use of debt and enormous pension fund, BAE doesn’t currently pass my investment quality criteria.

So does that mean BAE is guaranteed to be a bad investment over the next few years? Of course not; the future is far too uncertain to make such a bold statement. But it does mean I won’t be investing in BAE anytime soon.