The consequences of cyclical lending and the need for a new prudent framework.

I remember in the mid-to-late 1980s, when I was a relatively young, newly qualified valuation surveyor in London, I was constantly asking my peers, “why are the banks lending so much on commercial property? Surely, they know that there will be a recession around the corner?”

I never received a good answer to this inquisition; indeed, I rarely received a courteous response. Everyone was caught up in the boom, lending was strong and everybody from the banks to the agents to the developers in the property food chain were feeding well on strong bonuses and commissions. But then, in 1987, everything changed; prices crashed, and the banks started to bemoan losses and defaults and they were reeling in the shock that property values could fall and fall so much. I remember thinking at that point that banks didn’t understand market value (MV), and they erroneously thought that it was a magical figure that could and would never fall from the figure given at the loan’s commencement.

Bank Lending – a pro-cyclical pattern

I also remember working with the British Banking Association in the early 1990s when I made the radical suggestion that the loan-to-value (LTV) ratios were too high in property booms, and, conversely, too low in recessions. If you use the analogy of the peaks and troughs of a property cycle being equivalent to high mountains and low valleys, then the risk of being hurt if you fell was substantially higher at the top of the mountain than in the car park before or after the climb. Yet, the LTV criteria of banks – if you pardon my English – was “arse about face”; it allowed for more risk of prices falling in the downturns than in the up markets. Banks would lend at more preferential rates in booms based on higher LTVs (for commercial property up to 90% of MV) and at higher interest rates on lower LTVs (maybe as low as 40%) in the lows.

Later, I moved into academia. As an observer, I asked the same questions again in 1995 before the smaller crash of 1996/97 and, once again, in the late noughties before the onset of the financial economic crash (FEC) of 2008. It was constant déjà vu and the banks continued to lend too much in the booms as their LTVs were benchmarked on current market pricing as indicated by MV.

But the FEC did instigate new banking regulation to ensure that banks had systems and capital in place so they could withstand future crashes. The most significant of these initiatives was the expansion of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) in 2009 that has resulted in three “accords” designed to manage risk and capital. The latest, Basel III, has introduced the concept of “prudent value” for bank lending on property.

Basel III: responding to the financial crisis

Research from the Universities of Cambridge and Reading has identified that the majority of banks’ bad debts originate on loans made in the two years prior to the respective property crashes and that the bulk of defaults, in monetary terms, relate to commercial property lending.

Everyone should be united in ensuring that the framework for prudent value contained within Basel III is implemented consistently across the globe. That said, there are substantial issues of interpretation that need to be resolved. It is so important that all countries adopt a solution that is robust and deliverable and, most importantly, is substantively the same in all countries and jurisdictions. At the time of

writing, this is not a foregone conclusion.

At this point in time, the BCBS are proposing that each jurisdiction will identify the best way of meeting the requirements of “prudently conservative valuation criteria” of real estate loans by the 1 January 2025. However, that means that the UK may implement this differently to, say, the EU or the USA. We need a solution that works in all countries consistently and robustly.

Basel III discusses what is a “prudent valuation”. It reads: “Value of the property: the valuation must be appraised independently using prudently conservative valuation criteria. To ensure that the value of the property is appraised in a prudently conservative manner, the valuation must exclude expectations of price increases and must be adjusted to take into account the potential for the current market price to be significantly above the value that would be sustainable over the life of the loan.”

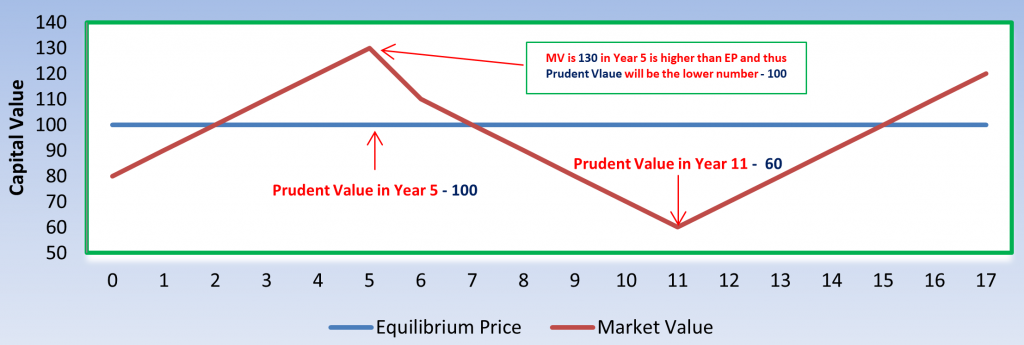

This is not a definition, but it identifies the interplay between MV and the concept of a long term “sustainable” value. In my eyes, this is an extrapolation of equilibrium price (EP) which can be very simply illustrated using an EP of 100 with MV varying from year to year (Figure 1).

Prudent value will be determined at each point by reference to which is lower; EP or MV as shown, for illustration, in year 5 and 11. This is easy to do retrospectively by analysing the historic data, but, of course, the role of prudent value going forward will need the calculation of both the EP/Long Term Sustainable Value/Economic Fair Value and MV. The latter can be provided by valuers, but EP will need to be calculated. The big question is who should calculate the adjustment factor and thus provide EP?

There is, in my opinion, an erroneous suggestion that the valuer should be responsible for advising on the appropriate adjustment so that he or she would also provide prudent value to the bank. Ignoring the minefield of possible litigation that this creates, this solution is also fraught with a lack of consistency as different valuers will suggest different adjustment factors. The adjustment factor needs to be consistent and not applied at the individual asset level.

Instead, what is needed is for all stakeholders to agree to develop and accept a single, consistent, market adjustment factor (ideally provided by the central bank in each country using the same econometric model) that can be applied by the lenders to the MV provided by the valuer. This adjustment factor can be updated and published at regular intervals to all lenders in the market. This is a model that can be applied in all jurisdictions to ensure the global consistency as the BCBS are advocating.

However, as I write, nothing has been decided and, indeed, until a framework for valuation for commercial and residential lending is agreed, valuers should continue to provide MV to their banking/lending clients.