In today’s dispatch:

- banks are lending less

- banks are also generating less revenue, and NIM continues to slide (for now)

- are Zombie banks good?

- bank exposure to non-bank lending is probably higher than Zombie would like

After the Fed nearly killed the banks by torpedoing the value of low-interest loans—the only kind of loans the Fed really allowed for over a decade—there has been a lot of effort to make banks “safer.”

Consistent with that effort, banks have worked pretty hard to not-lend because that’s what tightening up generally requires.

Banks are lending less

Outside of consumer credit card lending, banks have substantially ceded lending to non-bank banks, i.e. Private Credit, who have largely thrived in the higher rate environment.1

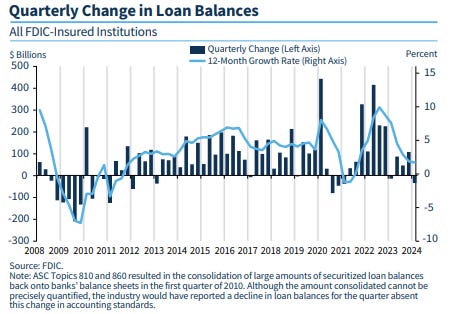

Credit card lending tends to be seasonal, so when it went negative last quarter (as it often does), so did bank lending overall:

Q1 loan balances contracted for the first time since early 2023 (which was the thick of the banking crisis).

In fairness, Q1 is historically a slow quarter, because again, seasonality, but the 12m loan balance growth rate is lower than its been since 2014.

Point is that banks are, in fact, lending less.

Lending less makes growing revenue hard to do

Of course, one thing about not-lending is that it has made it hard for banks to grow revenues (or balance-out all those low-interest loans they still hold).

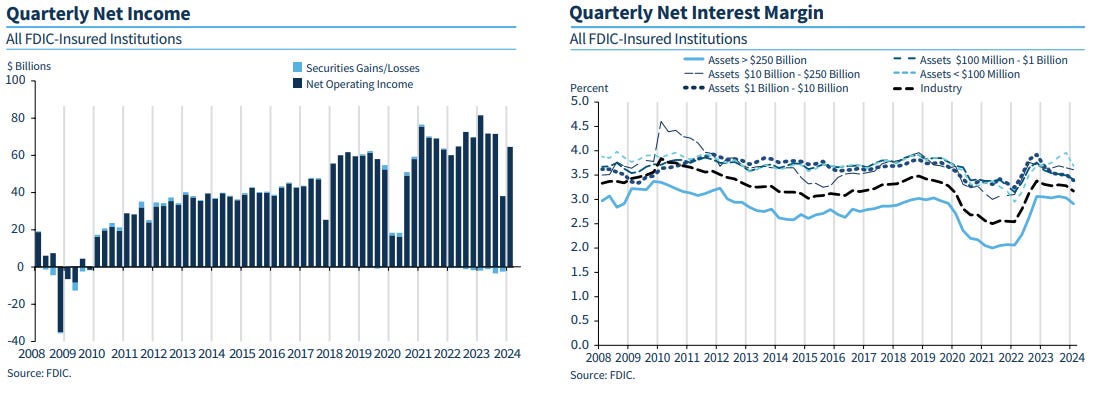

Banks may have to pay depositors more, but they should be able to charge borrowers more too . . . except, if they are too busy not-lending:

Bank revenues are flat-to-down, and NIM continues to trend downwards.

OK, so banks are trying to be safer, which means taking less risk, which means getting less-reward.

This is all according to plan. There are tradeoffs in all things, and this is the sort of tradeoff one would expect.

If banks become some zombies, is that good?

If safer, and less yieldy is indeed the future, it raises some open questions for the future of banks as we know them—if banks are unable or unwilling to find a market for higher cost loans, then they won’t be able to offset their higher cost of funding (and increase NIM).

In that scenario, banks become “zombies,” (i.e. they don’t generate enough yield to attract investors, but their loans are still money-good), and they function more like their European counterparts, as quasi-utilities.3

If that it is what’s happening (or even something short of that), it may well be a good thing because boring banks may be a good thing.

Boring keeps depositors safe.

Sure, we still need lending, but let the non-bank banks handle that, using investor money, instead of deposits. If someone wants to generate yield with their cash, they can freely give it to KKR or Apollo or some other private credit shop, who will lend it out in all kinds of long-term and/or exotic ways. Apollo and KKR can put all kinds of limitations around redemptions etc., so that there are no bank runs, and while investors can’t use their money as easily, they can generate yield.4

Borrow-long, lend-long.

If, however, someone just wants a safe place to put their salary that isn’t a mattress, then give it to a bank. There won’t be much yield, but there won’t be any liquidity issues either.

Borrow-short, lend-short.

The point is that if we can turn banks into ATM machines, and leave real lending to the professionals, then maybe we make banks boring, but we also make deposits safe, and that is good.

Or maybe not. My priors say ‘not’ because who wants a zombie anything, but reasonable minds can disagree.

At least banks have stayed out of the private credit game, right?

In all events, one thing is absolutely clear: the key to making it all work is that banks steer clear of the sorts of liquidity risks that are inherent to fractional reserve banking.

Banks need to stay in the ATM business, and not the big kids lending business.

It would be the worst of both worlds if banks stopped generating yield, but were still somehow exposed to the sort of lending that they are now trying not to do. Lending risk, with ATM rewards is no bueno.

You know where this is going, don’t you.

According to research from the NY Fed, it’s not exactly the worst of both worlds, but banks are a bit more exposed to Private Credit (or non-bank lenders) than a “boring” bank would like.

How? Well, banks might not do direct lending anymore, but they are lending to the lenders.

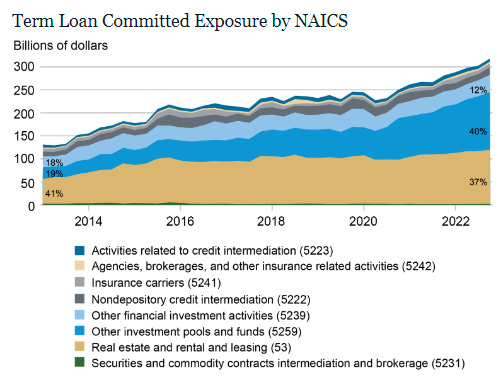

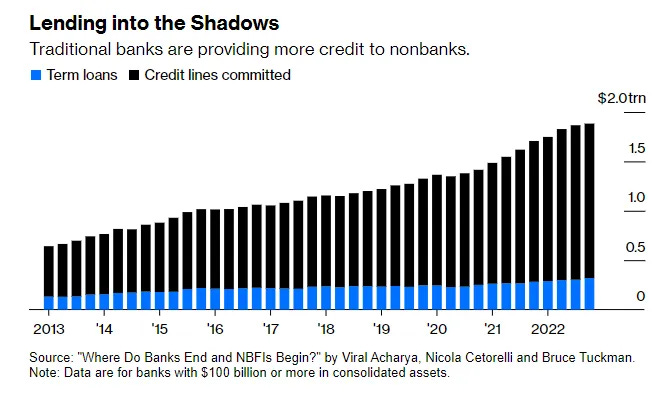

Banks have been lending to Private Credit for a while, and loans to Private Credit have grown with the industry:

Term loan commitments by banks to non-bank-banks grew by ~50% since 2020 alone.

That’s interesting so far as it goes, but what really has some hair on it aren’t the term loans. It’s the “contingent” credit lines that banks have provided non-bank lenders.

Contingent credit lines are are basically “break in case of emergency” sources of liquidity. In the ordinary course, letters of credit are super low risk. From the bank’s perspective, they’re relatively capital light because no one expects a line of credit to be pulled (and they don’t yield very much either). Of course, if the borrower does have an emergency, the bank might lose some money, but emergencies tend to be episodic and uncorrelated.

“Tend to be” are the magic words. For something more system-wide, uncorrelated risk becomes correlated in a hurry.

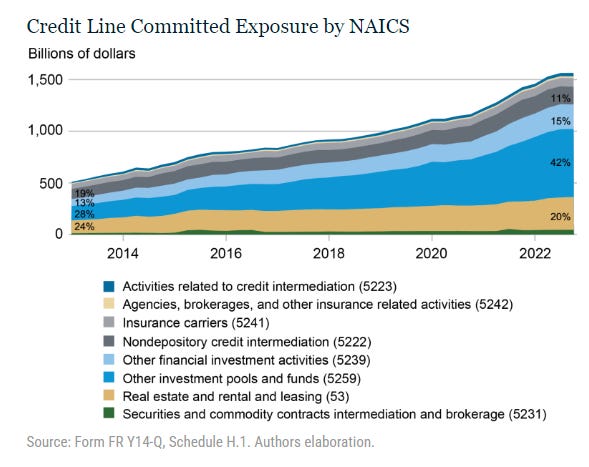

As it turns out, credit lines to non-bank lenders have also grown substantially:

Credit-line exposure is both substantially larger, and has grown more steeply over the last 10 years, than term loans.

One way of looking at it is ~$1.5T of exceedingly low-risk quasi-loans. And hey, that’s not so bad.

Another way of looking at it, is a $1.5T insurance policy to the private credit industry, should the whole thing get hit by a systemic liquidity crunch and thereby discover a burning need for “break in case of emergency” funds.

That would be quite bad.

Here’s what the whole stack looks like, courtesy of Bloomberg:

That’s ~$2T in total exposure to non-bank lenders.

So, rather than insulating themselves from a broader liquidity event—the whole point of leaving big kid lending (and big kid yields) behind—banks are insuring the entire industry, against the very risk the banks are working so strenuously to avoid.

Fantastic.

In fairness to banks, the growth of these credit lines clearly tapered along with everything else, so this isn’t some “durr, how can they be so stupid.” A lot of the bets were already placed.

Plus, these are crude generalizations, and lines of credit often have collateral, or other protections, in place (and they may not all be “break in case of emergency” lines of credit, either).

Finally, regulators are clearly aware of the issue, hence the NY Fed report.

Still, whatever transition to boring banking may be underway (or not), it’s clear that we’re not there yet.

This article was originally published in The Random Walk and is republished here with permission.