Like a pillion passenger leaning in the opposite direction to the rider, UK banks’ behaviour has become perverse and dangerous. Banks are engaged in an elaborate risk management exercise that seeks to enhance their profitability, defend their reputation, and conserve their capital. Their role as universal credit providers to individuals and non-financial businesses is being increasingly subordinated to these other considerations. Their willingness to withdraw from the marketplace – in terms of physical footprint, product range and customer profile – is symptomatic of their reordered priorities. Armed with real-time information on the profitability of customer accounts, banks are penalising customer inertia, alias loyalty, and tightening the qualifying criteria for keeping an account open. Above all, they have a heightened aversion to loan losses.

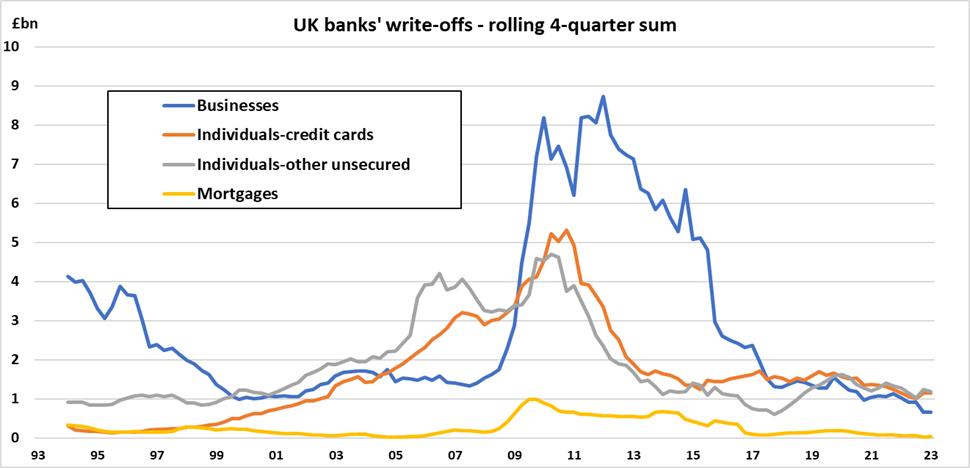

An examination of the chart for UK banks’ loan write-offs betrays no evidence of a pandemic, nor that much of the economy was paralysed for months on end. The banks have passed the bill for Covid-related loan losses to the taxpayer. Remarkably, banks’ total write-offs have fallen from a £5 billion annual rate in 2019 to little more than £3 billion in the year to the first quarter of 2023 (Figure 1).

Figure 1

When the GFC erupted in 2007-08, the nature of commercial banking would soon be transformed by regulatory interventions. Alongside the traditional role of credit intermediation, banks were forced to become professional risk managers. Liquidity and solvency risks that they had previously assumed to be covered by the central bank, landed back in their lap. In consequence, banks became much more cautious in their lending to the real economy. Year after year, loan growth languished despite very low interest rates. Post-GFC, the government sent an expansionary message with historically low interest rates while simultaneously sending a contractionary message with its regulatory impositions. Like a car whose driver has one foot pressed down on

the accelerator and the other pressed down on the brake, the wheels of the economy were spinning but the vehicle was stationary.

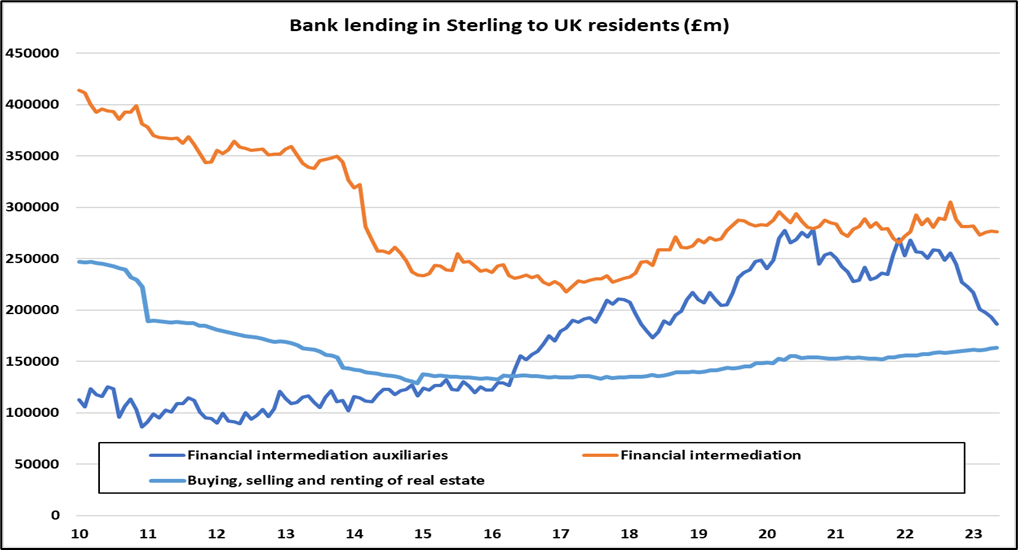

Over the past 18 months, UK banks are at it again, confiscating the umbrellas before the real downpour arrives! They are reinforcing the impact of rising policy interest rates with a tightening of lending conditions, similar in severity to that in 2007-09 (Figure 2). The effective interest rate paid on new mortgage loans is 170 basis points higher than for outstanding loans; a year ago, there was no difference. There remains no difference between the rates for new and outstanding business loans. Net mortgage lending by monetary institutions has slumped from a quarterly rate of £16.9 in Q1 2022 to £3.76 billion in Q1 2023 and minus £1 billion in Q2. Banks are making great efforts to restrict net lending to individuals and to contract net lending to businesses, especially financial businesses. Figure 3 reveals that it is the financial auxiliaries (mainly fund managers) whose borrowing has been most severely curtailed. One might ask why they needed to borrow so much in the first place?

Figure 2

Commercial banks are on a mission to extract themselves from their traditional exposures to consumers and small businesses. A rich variety of shadow banks have emerged – insurance companies, credit providers, leasing companies etc. – non-bank financials who are the marginal providers of credit to real economy borrowers. Since the GFC, the banks have prioritised the funding of other financial intermediaries above lending directly to individuals and small and medium-sized enterprises. This has two advantages for the banks: it distances them from the painful human consequences of rising rates, and it offers them a better risk-adjusted return. In a recession, the banks might still take a hit on their loan book, but more from lending to failing non-bank financials, and less from lending directly to the public.

Figure 3

Rather than offering their depositors a decent rate of interest (until very recently) as a buffer against the adverse impacts of inflation, they are withholding return in a bid to protect their capital from prospective loan losses. In desperation, the government is attempting to shame the banks into concessions, seeking to recompense savers and soften the blow of resetting mortgages and avert the spectacle of a pre-election wave of house possessions. While they will argue that they are acting prudently, from a broader perspective, banks have become rogue actors to the frustration of consumers, SMEs, and government alike.

Policymakers can no longer have any confidence that a cut in short-term interest rates will have an expansionary effect on bank lending to the real economy, but they can be more confident that a hike in interest rates will have a restraining impact. While the Bank of England was purchasing gilts, it imparted a stimulus to bank lending to the non-bank financial sector; on the expectation of rising financial asset prices. Since the Bank has adopted quantitative tightening, it has removed another motivation for loan growth. Far from acting as shock absorbers for their customers, the banks are amplifying the shocks.