Last week, polling for CapX found broad agreement that there is a housing crisis in Britain, though people in all regions thought it was less bad in their local area, with politicians the most likely culprits in the eyes of voters.

This week we turn to opponents of development – habitually feared by governments – the NIMBYs, together with those who support it.

Like many things, the concept has existed far longer than the term. The first documented use of the latter is in 1980, but opposition to local development has been around far longer, and reference can even be found in the Old Testament. But who are these NIMBYs, and what motivates them?

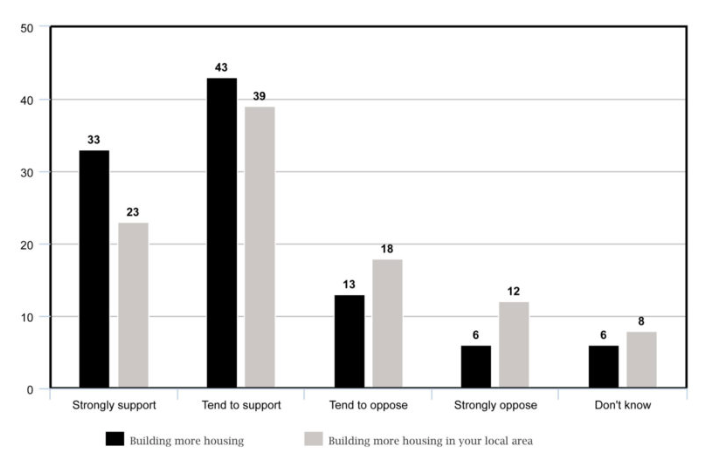

The latest Number Cruncher polling for CapX asked respondents how they felt about building more housing, firstly without qualification, and then specifically in their local area.

Given the acceptance of a housing crisis by about three-quarters of Brits reported previously, it’s perhaps not surprising that a similar proportion (76 per cent) support building more houses, with 19 per cent opposed. And again, the pattern of variation between groups – or rather the general lack thereof – was apparent.

Labour voters were less likely than Tories to oppose building, as were Remainers, Londoners and renters, although the subsample sizes here aren’t quite big enough to rule out statistical noise.

One unexpected thing we found was a six-point gender gap, with 22 percent of women opposing building more houses, compared with only 16 percent of men. This isn’t explained by a gender difference in don’t

What about locally? Well, opposition is much higher, as you’d expect. But we are not a nation of NIMBYs. Sixty-two per cent support building more housing in their local area, double the proportion (30 per cent) who oppose it.

In terms of who stands where, 2017 Conservative (37 per cent) and Lib Dem (39 per cent) voters are the likeliest to be NIMBYs, while Labour (23 per cent) and non-voters (22 per cent) are least likely. Ethnic minorities (20 per cent) were less likely than white respondents (31 per cent) to oppose local development, and renters were less likely than homeowners.

The local versus national difference in support for building homes mirrors the pattern on the housing crisis question. This could be a case of people unconsciously aligning views on the problem and its solution, as people sometimes do. But as Ben Page has pointed out, the same occurs with immigration and the NHS, so the divergence could be a result of a genuine difference in how people see their own area vis-a-vis the country as a whole.

It will be welcome news to anyone supporting house-building that there are twice as many YIMBYs as NIMBYs. But NIMBYs do still exist, and in sufficient numbers to matter electorally, particularly if the perceived downsides of development outweigh (or arrive sooner than) the benefits.

So we then asked which of a list of arguments against building more local housing people found most persuasive, from which they could chose up to three. This was asked to everyone, but the same arguments seemed to resonate with NIMBYs as with the electorate as a whole, the only real difference being that the latter were much likely to use all three of their options, as you’d expect.